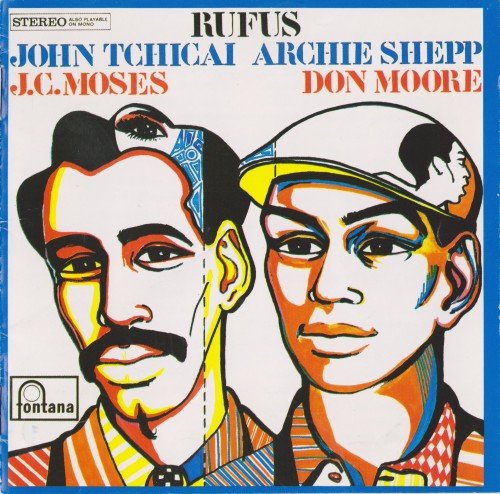

John Tchicai / Archie Shepp - Rufus (1990)

Artist: John Tchicai / Archie Shepp

Title: Rufus

Year Of Release: 1990

Label: Fontana [PHCE-1002]

Genre: Free Jazz, Free Improvisation

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, log, Artwork)

Total Time: 48:20

Total Size: 309.9 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Rufus

Year Of Release: 1990

Label: Fontana [PHCE-1002]

Genre: Free Jazz, Free Improvisation

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, log, Artwork)

Total Time: 48:20

Total Size: 309.9 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Rufus

02. Nettus

03. Hoppin'

04. For Helved

05. Funeral

Since the end of the 1950's the dominant approach to improvising music has been that of "The New Thing". The generation of players sired by Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor has successfully asserted the right of the artist to abandon metrical form and fixed tempi, to dispense with the restrictions of tonality, and to play notes which have no place in the European scale. Judging the "New Thing" school on the basis of its words, free improvisation of this kind might sound like artistic irresponsibility - or else an assertion that all sounds have an equal claim to our attention. Judging it on its deeds, however, one is struck by the way its members have shied away from such implications. Every player has voluntarily limited his means of expression, selected a particular musical vision as the pattern to which his work shall conform, and then tried to perfect his work inside comparatively narrow limits. In fact the rules have not been renounced but recreated, with the difference that the new rules are chosen to meet individual needs and make no pretensions to universal significance.

Archie Shepp and John Tchicai possess strongly contrasted conceptions of musical order, and these conceptions had crystallised by the time they toured Scandinavia in late 1963 as members of the New York Contemporary Five. ("Consequences", an LP by that gr oup, is also available on Fontana). At the end of the tour the group, with the exception of trumpeter Don Cherry, made this LP. Thereafter the difference in approach between the two saxophonists took their careers in opposite directions, leading to their present eminence as two of the principal improvisers and composer-leaders in "The New Thing". This LP, however, presents them side by side, and the contrast between their approaches illuminates the playing of both musicians.

Shepp's dramatic style emphasises the descent of the music from jazz; it has also helped him to become the first "New Thing"-player to enjoy widespread success with jazz audiences. His hairy-chested manner is full of references to the more extrovert jazz tenor saxophonists. A fondness for tempering a full, rich sound with breathy intimacies, growling ferocities, and slurs and swoops in the manner of Lockjaw Davis and Ben Webster goes hand in hand with hard-toned, implacable passages recalling Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, and with raucous honking and a raw, folk quality in the rhythm-and-blues tradition. His melodic shapes seem equally orthodox to jazz ears - a collage of loosely related or discontinuous phrases held together by a directly emotional a ppeal and capable of generating enormous impetus and excitement, as happens notably towards the end of "For Helved". Yet another link with the past is Shepp's fierce rhythmic attack and his preference for a direct and swinging accompaniment from bass and drums, the kind to be heard on the first four tracks of this LP.

The uniquely gifted Tchicai adopts a totally opposite approach. His attractively reedy and liquid timbre is unlike that of any other alto saxophonist. His stance is intimate rather than rhetorical and he makes no attempt to communicate any specific state of mind; the high degree of urgency and expressiveness in his work seems to derive from intellectual passion. Tchicai uses a method of construction analagous to that of classical European composers; each solo is a closely argued discourse in which a single motif is developed, transformed and often repeated, the whole making rigorous sense as a self-contained melodic line. He is also a more strictly linear improviser than Shepp, as can be gathered from his later work with the New York Art Quartet ("Mohawk" , for example, also on Fontana). The lyrical simplicity of his phrases and his generous use of rests seem to invite the supporting bass and drums to join in with him, and his airy, floating rhythms do not really need the lusty and straightforward time-keeping to be found here. (The remarkable New York Art Quartet concerns itself solely with true collective improvisation at constantly varying tempi, the distinction between soloist and accompanist, so pronounced here, vanishing yet without submerging the gifts of the separate members.)

Archie Shepp and John Tchicai possess strongly contrasted conceptions of musical order, and these conceptions had crystallised by the time they toured Scandinavia in late 1963 as members of the New York Contemporary Five. ("Consequences", an LP by that gr oup, is also available on Fontana). At the end of the tour the group, with the exception of trumpeter Don Cherry, made this LP. Thereafter the difference in approach between the two saxophonists took their careers in opposite directions, leading to their present eminence as two of the principal improvisers and composer-leaders in "The New Thing". This LP, however, presents them side by side, and the contrast between their approaches illuminates the playing of both musicians.

Shepp's dramatic style emphasises the descent of the music from jazz; it has also helped him to become the first "New Thing"-player to enjoy widespread success with jazz audiences. His hairy-chested manner is full of references to the more extrovert jazz tenor saxophonists. A fondness for tempering a full, rich sound with breathy intimacies, growling ferocities, and slurs and swoops in the manner of Lockjaw Davis and Ben Webster goes hand in hand with hard-toned, implacable passages recalling Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, and with raucous honking and a raw, folk quality in the rhythm-and-blues tradition. His melodic shapes seem equally orthodox to jazz ears - a collage of loosely related or discontinuous phrases held together by a directly emotional a ppeal and capable of generating enormous impetus and excitement, as happens notably towards the end of "For Helved". Yet another link with the past is Shepp's fierce rhythmic attack and his preference for a direct and swinging accompaniment from bass and drums, the kind to be heard on the first four tracks of this LP.

The uniquely gifted Tchicai adopts a totally opposite approach. His attractively reedy and liquid timbre is unlike that of any other alto saxophonist. His stance is intimate rather than rhetorical and he makes no attempt to communicate any specific state of mind; the high degree of urgency and expressiveness in his work seems to derive from intellectual passion. Tchicai uses a method of construction analagous to that of classical European composers; each solo is a closely argued discourse in which a single motif is developed, transformed and often repeated, the whole making rigorous sense as a self-contained melodic line. He is also a more strictly linear improviser than Shepp, as can be gathered from his later work with the New York Art Quartet ("Mohawk" , for example, also on Fontana). The lyrical simplicity of his phrases and his generous use of rests seem to invite the supporting bass and drums to join in with him, and his airy, floating rhythms do not really need the lusty and straightforward time-keeping to be found here. (The remarkable New York Art Quartet concerns itself solely with true collective improvisation at constantly varying tempi, the distinction between soloist and accompanist, so pronounced here, vanishing yet without submerging the gifts of the separate members.)

![Martin Fabricius & Chris Lavender - The Speed of Why (2010) [Hi-Res] Martin Fabricius & Chris Lavender - The Speed of Why (2010) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771254824_cover.jpg)

![Pasquale Cataldi - Maybe (2026) [Hi-Res] Pasquale Cataldi - Maybe (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771154794_shtkhljffl929_600.jpg)

![Ragini Trio - 3 (2026) [Hi-Res] Ragini Trio - 3 (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/19/uoki2dxo3dfz215xa2kz53gcp.jpg)