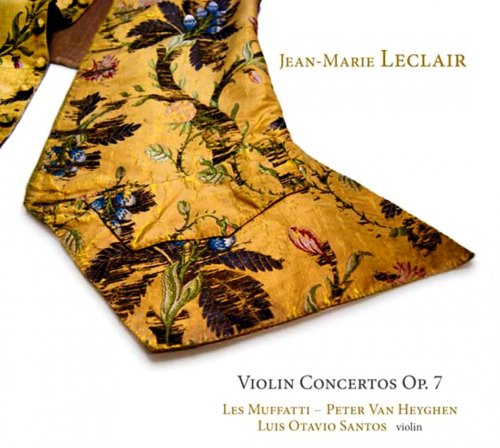

Luis Otavio Santos, Les Muffatti, Peter Van Heyghen - Leclair: Violin Concertos Op.7 (2012) Hi-Res

Artist: Luis Otavio Santos, Les Muffatti, Peter Van Heyghen

Title: Leclair: Violin Concertos Op.7

Year Of Release: 2012

Label: Ramee

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks) 24/96

Total Time: 77:38

Total Size: 1,64 Gb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Leclair: Violin Concertos Op.7

Year Of Release: 2012

Label: Ramee

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks) 24/96

Total Time: 77:38

Total Size: 1,64 Gb

WebSite: Album Preview

Concerto No.5 in A minor

1. I.Vivace

2. II.Largo – Adagio

3. III.Allegro assai

Concerto No.2 in D major

4. I.Adagio

5. II.Allegro ma non troppo

6. III.Adagio

7. IV.Allegro

Concerto No.4 in F major

8. I.Allegro moderato

9. II.Adagio

10. III.Allegro

Concerto No.1 in D minor

11. I.Allegro

12. II.Aria Gratioso

13. III.Vivace

Concerto No.6 in A major

14. I.Allegro ma non presto

15. II.Aria Grazioso non troppo adagio

16. III.Giga Allegro

Performers:

Luis Otavio Santos, violin

Les Muffatti

Peter Van Heyghen, direction

Leclair’s op. 7 collection of violin concertos, published in 1737, wasn’t the first by a French composer, but it was the first to draw great praise. Critic and professor of humanities Noël-Antoine Pluche listed Leclair among the “composers of the first rank,” and composer Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville famously wrote in 1758 that he was the Corelli Read more Four Seasons continues to leave all his contemporary competition in the shade.

But it was Leclair who pushed the soloist’s technique further with left-hand tremolos, and double-stops that achieve a typically French thematic prominence in a few movements. His employment of Veracini-like canon and fugal textures (the second movement of the Concerto II, the piquant finale of the Concerto I) and imitation (Concerto VI, opening Allegro ) are both distinctive in themselves and perfectly suited to the character of the movements in which they are employed. Some of his solos utilize motivic elements from ripieno statements to launch original themes, a process that he may have picked up from Italian concerti grossi. Then, too, most of his slow movements (the French pastoral of the Concerto VI is an exception) have a fluid, Italianate grace that match those of Corelli and Vivaldi at their respective best.

These performances are refined but vigorous, emphasizing textural detail without neglecting rhythmic vitality. Heyghen and Les Muffatti, whom I previously praised in a disc of Pez’s orchestral music ( Fanfare 31:5), are precise in their attacks, and supple in phrasing. A sensible variety of tempos are chosen, without slighting the Adagio markings of slower movements. String tone is warm, with discreet vibrato. Luis Otavio Santos’s performance of several Leclair violin sonatas was received warmly by Brian Robbins ( Fanfare 29:3), and my opinions are similar to his on this release. Santos is always suave and stylistically assured. A very few insecure moments to one side in the Concerto VI’s opening movement, he meets the considerable demands of this music with seeming ease. He is always engaged with this music, but never anachronistic.

Among other recordings, Simon Standage/Collegium Musicum 90 (Chandos 551; 564; 589) is competitive, with a darker string tone and a larger ensemble, but the violinist’s expressive reticence renders his otherwise attractive readings a shade less appealing. On the positive side, they include the op. 10 as well, but Santos is still to be preferred. With excellent sound and balance, let’s hope that these musicians take their cue from Standage, and continue with Leclair’s 1745 collection of violin concertos. --- Barry Brenesal

But it was Leclair who pushed the soloist’s technique further with left-hand tremolos, and double-stops that achieve a typically French thematic prominence in a few movements. His employment of Veracini-like canon and fugal textures (the second movement of the Concerto II, the piquant finale of the Concerto I) and imitation (Concerto VI, opening Allegro ) are both distinctive in themselves and perfectly suited to the character of the movements in which they are employed. Some of his solos utilize motivic elements from ripieno statements to launch original themes, a process that he may have picked up from Italian concerti grossi. Then, too, most of his slow movements (the French pastoral of the Concerto VI is an exception) have a fluid, Italianate grace that match those of Corelli and Vivaldi at their respective best.

These performances are refined but vigorous, emphasizing textural detail without neglecting rhythmic vitality. Heyghen and Les Muffatti, whom I previously praised in a disc of Pez’s orchestral music ( Fanfare 31:5), are precise in their attacks, and supple in phrasing. A sensible variety of tempos are chosen, without slighting the Adagio markings of slower movements. String tone is warm, with discreet vibrato. Luis Otavio Santos’s performance of several Leclair violin sonatas was received warmly by Brian Robbins ( Fanfare 29:3), and my opinions are similar to his on this release. Santos is always suave and stylistically assured. A very few insecure moments to one side in the Concerto VI’s opening movement, he meets the considerable demands of this music with seeming ease. He is always engaged with this music, but never anachronistic.

Among other recordings, Simon Standage/Collegium Musicum 90 (Chandos 551; 564; 589) is competitive, with a darker string tone and a larger ensemble, but the violinist’s expressive reticence renders his otherwise attractive readings a shade less appealing. On the positive side, they include the op. 10 as well, but Santos is still to be preferred. With excellent sound and balance, let’s hope that these musicians take their cue from Standage, and continue with Leclair’s 1745 collection of violin concertos. --- Barry Brenesal

![Owelu Dreamhouse - Owelu Dreamhouse (2026) [Hi-Res] Owelu Dreamhouse - Owelu Dreamhouse (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/05/dyetvafic12nz1s9v6zs98erj.jpg)