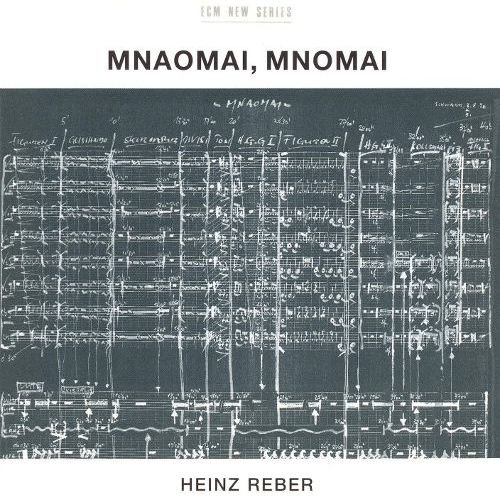

Heinz Reber - Mnaomai, Mnomai (1991)

Artist: Heinz Reber

Title: Mnaomai, Mnomai

Year Of Release: 1991

Label: ECM New Series

Genre: Jazz, Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log)

Total Time: 40:18

Total Size: 188 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Mnaomai, Mnomai

Year Of Release: 1991

Label: ECM New Series

Genre: Jazz, Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log)

Total Time: 40:18

Total Size: 188 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Part I

02. Part II

03. Part III

04. Part IV

Personnel:

Thomas Demenga - cello, viola

Terje Rypdal - guitar

Jon Christensen - drums

Tschin Zhang - vocal

Ellen Horn - vocal

The Swiss composer Heinz Reber (1952-2007) cut a fascinating figure in the world of sound. He began his career as a music therapist for psychiatric patients before turning to more public forms of audible expression. Reber would even combine the two in a 1975 play for Swiss radio, the cast of which was culled from those same patients. Such ruptures of identity would characterize his output to come. For the spiraling exegesis that is Mnaomai, Mnomai, Reber assembled a handful of equally committed (no pun intended) instrumentalists and vocalists for an intriguing mélange of sound and spoken word. The word mnaomai (pronounced “mnah’-om-ahee”) appears in the New Testament and means “to bear in mind” in Greek. Reber lifted his title from Jean-François Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy. Although the source texts are interesting in and of themselves—ranging from Beckett to Chinese protest poetry written by Tschin Zhang, one of the album’s vocal performers—they constitute a set of linguistic entities whose orthographic shapes are as equally important as their verbal ones. Thomas Demenga’s viola seems to struggle through its opening while a low groan stretches in the background. Demenga scrounges for phonetic footholds as Zhang’s voice rings out like a light to show the way. Jon Christensen and Terje Rypdal each take their own direct approach, even while Demenga continues to wrestle with his communicative role. Zhang’s voice soars through a field of strings with the surety of a homing pigeon, while that of Ellen Horn creeps in from above, percolating through Zhang’s as if to strip these languages of their semantic egos. Sometimes the voices are present, other times they are distant, but they never stray from their message. Part III consists of a repeated figure on viola, as if Demenga’s instrument has finally found a solid phrase and is reveling in its repetition. This is followed by a final spurt of poetic energy that fizzles out into a delicate cello strum.

In closing, I should like to address a concern I have over a particular way in which this piece has been interpreted. Mnaomai, Mnomai contains a fair amount of spoken Mandarin, and for those of us who don’t speak the language it’s all too easy to over-romanticize Chinese for its rhythms and other idiosyncrasies. This seemingly impenetrable barrier is further strengthened by the addition of Horn’s quieter recitations, of which Steve Lake writes: “When bringing Ellen Horn’s voice into the ensemble, Tschin Zhang’s poem was converted into Norwegian, another ‘alien’ tongue, to keep the text as a pure play of sounds.” But “pure” to whom? Surely, heritage speakers of either language will have a difficult time treating the text as a meaningless, if enchanting, jumble of phonemes. Rather, they will hear a skillful recitation of a heartfelt poem written in a time of great political upheaval. Are they somehow missing the point? I doubt it. In spite of Reber’s supposed interest in the “Far East,” I don’t feel as if he is using the world’s most populously spoken language just for the sound of it. Otherwise, what would be the purpose of using words at all? Chinese is itself no more “beautiful” or “musical” than any other language, and any assertions to the contrary are simply a matter of opinion. In the end, Reber cannot be said to be tapping in to some mystical linguistic core, but rather creating a new and personal juxtaposition of music and speech as a means of teasing out the narrative potential in both. Neither can we ignore that the musicians, and Demenga in particular, are also “speaking” through a multi-instrumental conversation. Still, I think Lake is getting at the heart of this record: namely, that language’s fundamentally arbitrary vocabularies are like composed matter—static and silent until they are enlivened by human rendering. It all comes down to the transparency of the utterance. This is music interested not in its legacy, but in its disintegration, for as the title reminds us, we do well to “bear in mind” that meaning exists only insofar as it holds our interest.

In closing, I should like to address a concern I have over a particular way in which this piece has been interpreted. Mnaomai, Mnomai contains a fair amount of spoken Mandarin, and for those of us who don’t speak the language it’s all too easy to over-romanticize Chinese for its rhythms and other idiosyncrasies. This seemingly impenetrable barrier is further strengthened by the addition of Horn’s quieter recitations, of which Steve Lake writes: “When bringing Ellen Horn’s voice into the ensemble, Tschin Zhang’s poem was converted into Norwegian, another ‘alien’ tongue, to keep the text as a pure play of sounds.” But “pure” to whom? Surely, heritage speakers of either language will have a difficult time treating the text as a meaningless, if enchanting, jumble of phonemes. Rather, they will hear a skillful recitation of a heartfelt poem written in a time of great political upheaval. Are they somehow missing the point? I doubt it. In spite of Reber’s supposed interest in the “Far East,” I don’t feel as if he is using the world’s most populously spoken language just for the sound of it. Otherwise, what would be the purpose of using words at all? Chinese is itself no more “beautiful” or “musical” than any other language, and any assertions to the contrary are simply a matter of opinion. In the end, Reber cannot be said to be tapping in to some mystical linguistic core, but rather creating a new and personal juxtaposition of music and speech as a means of teasing out the narrative potential in both. Neither can we ignore that the musicians, and Demenga in particular, are also “speaking” through a multi-instrumental conversation. Still, I think Lake is getting at the heart of this record: namely, that language’s fundamentally arbitrary vocabularies are like composed matter—static and silent until they are enlivened by human rendering. It all comes down to the transparency of the utterance. This is music interested not in its legacy, but in its disintegration, for as the title reminds us, we do well to “bear in mind” that meaning exists only insofar as it holds our interest.