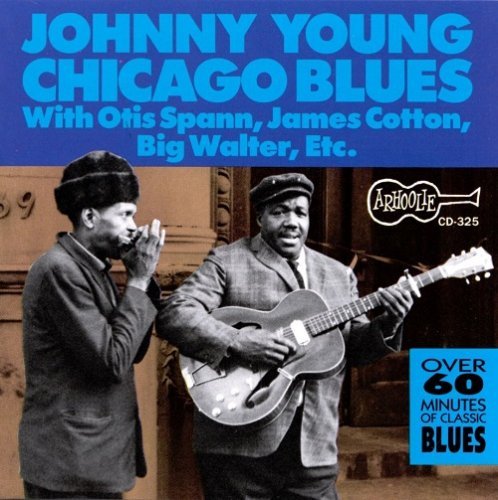

Johnny Young - Chicago Blues (With Otis Spann, James Cotton, Big Walter) (Reissue) (1968/1990) Lossless

Artist: Johnny Young

Title: Chicago Blues

Year Of Release: 1968/1990

Label: Arhoolie Records

Genre: Acoustic / Electric Chicago Blues

Quality: APE (image, .cue, log)

Total Time: 01:05:20

Total Size: 399 Mb (scans)

WebSite: Album Preview

Title: Chicago Blues

Year Of Release: 1968/1990

Label: Arhoolie Records

Genre: Acoustic / Electric Chicago Blues

Quality: APE (image, .cue, log)

Total Time: 01:05:20

Total Size: 399 Mb (scans)

WebSite: Album Preview

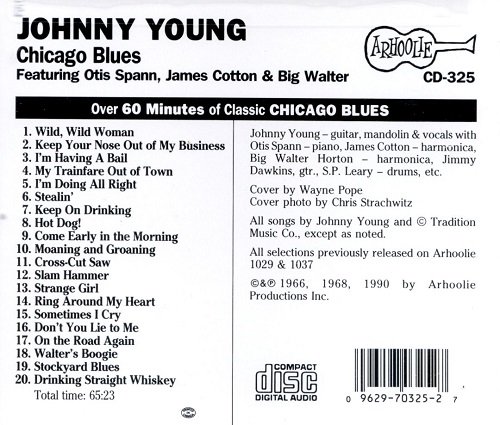

Tracklist:

01. Wild, Wild Woman 02:37

02. Keep Your Nose Out Of My Business 03:16

03. I'm Having A Ball 02:54

04. My Trainfare Out Of Town 02:43

05. I'm Doing All Right 03:30

06. Stealin' 02:40

07. Keep On Drinking 03:21

08. Hot Dog! 02:02

09. Come Early In The Morning 03:04

10. Moaning And Groaning 03:17

11. Crosscut Saw 02:36

12. Slam Hammer 01:41

13. Strange Girl 03:37

14. Ring Around My Heart 04:48

15. Sometimes I Cry 02:50

16. Don't You Lie to Me 03:43

17. On The Road Again 04:51

18. Waiter's Boogie 03:33

19. Stockyard Blues 03:20

20. Drinking Straight Whiskey 03:37

Line-up:

Bass – Ernest Gatewood (tracks: 13 to 20), Jimmy Lee Morris (tracks: 1 to 12)

Drums – Lester Dorsie (tracks: 13 to 20), S.P. Leary (tracks: 1 to 12)

Harmonica – James Cotton (tracks: 1 to 12), Walter Horton (tracks: 13 to 20)

Lead Guitar – Jimmy Dawkins (tracks: 13 to 20)

Mandolin – Johnny Young (3) (tracks: 1 to 12)

Piano – Lafayette Leake (tracks: 13 to 20), Otis Spann (tracks: 1 to 12)

Vocals, Guitar – Johnny Young (3)

Although the mandolin is not an instrument commonly associated with Chicago blues, it has been used by Chicago-based string bands or on Chicago-made recordings by artists such as Carl Martin, Charles and Joe McCoy, and Yank Rachell. However, the only artist to use it successfully in the later electric blues format was Mississippi-born bluesman Johnny Young.

An important figure in blues history, Young loved the rough-and-tumble string band tradition of the Delta, a style that readily co-existed with blues.

Young's initial 1947 Chicago classic, "Money Taking Women," exhibits the same exuberant down-home sound, fusing blues with the older country breakdown traditions. The string band ensemble sound suited street performance as well, whether in Memphis or in Chicago's open air Maxwell Street Market, where Young and his cronies were brought in off the streets to record. Over the years, Young's mandolin activity declined as Chicago's African-American blues audience demanded a more modern and urban sound. Since Young was also a skilled guitarist and a fine vocalist, he easily weathered the transition.

During the late '60s, an emerging white blues-revival audience proved eager for Young's mandolin styling. Unlike Yank Rachell, whose mandolin playing retained an older string band feel, Young's style was firmly grounded in a more contemporary postwar blues idiom, and he interacted well with other electric blues artists. Throughout his life, he had worked with the major figures of blues history, including Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, Walter Horton, and Otis Spann. He was, he insisted, born to be a musician. When interviewed shortly before he died, he said he had struggled all his life trying to make it in the music business. An emotional man, he hoped he would live long enough to make enough money to buy a house. He never made it.

An important figure in blues history, Young loved the rough-and-tumble string band tradition of the Delta, a style that readily co-existed with blues.

Young's initial 1947 Chicago classic, "Money Taking Women," exhibits the same exuberant down-home sound, fusing blues with the older country breakdown traditions. The string band ensemble sound suited street performance as well, whether in Memphis or in Chicago's open air Maxwell Street Market, where Young and his cronies were brought in off the streets to record. Over the years, Young's mandolin activity declined as Chicago's African-American blues audience demanded a more modern and urban sound. Since Young was also a skilled guitarist and a fine vocalist, he easily weathered the transition.

During the late '60s, an emerging white blues-revival audience proved eager for Young's mandolin styling. Unlike Yank Rachell, whose mandolin playing retained an older string band feel, Young's style was firmly grounded in a more contemporary postwar blues idiom, and he interacted well with other electric blues artists. Throughout his life, he had worked with the major figures of blues history, including Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters, Walter Horton, and Otis Spann. He was, he insisted, born to be a musician. When interviewed shortly before he died, he said he had struggled all his life trying to make it in the music business. An emotional man, he hoped he would live long enough to make enough money to buy a house. He never made it.

![Louis Matute - Dolce Vita (2026) [Hi-Res] Louis Matute - Dolce Vita (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/10/7o1gz4rkolmyer0yu89vuy268.jpg)