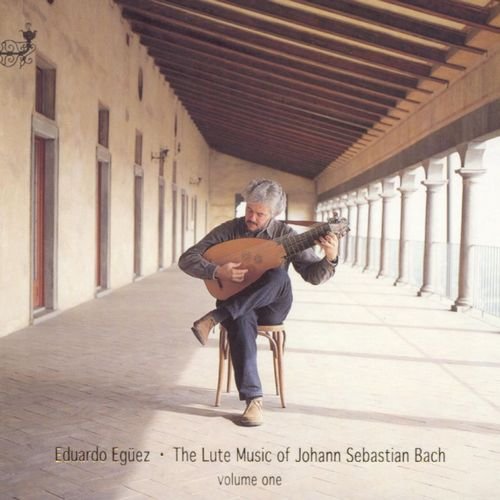

Eduardo Egüez - The Lute Music of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume One (2001)

Artist: Eduardo Egüez

Title: The Lute Music of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume One

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: MA Recordings

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:01:18

Total Size: 327 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: The Lute Music of Johann Sebastian Bach, Volume One

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: MA Recordings

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:01:18

Total Size: 327 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Prelude, Fugue And Allegro, For Lute In E Flat Major, Bwv 998 (Bc L132)

1 – I. Prélude 3:10

2 – II. Fuga 6:28

3 – III. Allegro 3:48

Suite For Lute In G Minor, Bwv 995

4 – I. Prélude - 'Tres Viste' 5:26

5 – II. Allemande 5:35

6 – III. Courante 2:34

7 – IV. Sarabande 2:20

8 – V. Gavotte 2:13

9 – Vi. Gavotte 2 En Rondeau 2:33

10 – VII. Gigue 2:45

Partita For Lute In C Minor, Bwv 997 (Bc L170)

11 – I. Praelude 3:39

12 – II. Fuga 8:22

13 – III. Sarabande 5:41

14 – IV. Gigue 3:12

15 – V. Double 3:32

Eduardo Egüez (lute)

The issue of authenticity of Bach’s so-called lute music is one that continues to perplex artists today; most of the recordings of Bach’s lute music range from transcriptions of the cello and certain solo violin suites to other more capriciously chosen works that are made to “fit” the instrument. Indeed, one of the best (and most popular) of such collections, that by Nigel North (Linn Records, “Bach on the Lute”), consists entirely of these violin and cello works, albeit with the not-uncommon idea of such works finding their way into the repertoire of all sorts of related instruments.

What Egüez has done is to give us those works that are substantially sustainable in the idea of actually having been played on the lute. Speculation as to how many of Bach’s works ended up being played on the instrument is of course pointless and to a certain degree impossible to determine. His selection of the specific works on these two discs comes with a reasonable assumption of the notes having actually graced lute strings. One of false assumptions is that any work determined to have been played on an instrument called the Lautenwerk might have made its way to the lute proper. This instrument, a keyboard mechanism that used gut strings and was noted for its formidable dynamic range, was developed in great part by Bach himself, but, according to contemporaries, sounded more like a theorbo than a lute. The usually included BWV 996 is omitted in this collection because the only thing that this work really has in common with a lute is the word “Lautenwerck” in the copy manuscript by (possibly) Johann Tobias Krebs. Otherwise, according to Egüez, “the extension of registry and density of counterpoint in some way exceed the adaptation possibilities of the piece to any type of lute (at least those currently known).”

Yet we know that Bach had connections with the great lutenist Silvius Weiss, for whom he may have composed the Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro, BWV 998, and the manuscript is Bach’s. So the lute was definitely within his purview, even if we cannot be sure which pieces fit the mold. The sourcing may be unreliable—and we still don’t know if or how well Bach may have played the instrument—but the existence of the lute in his circle or that of his students is without question.

BVW 995 is of especial interest since the manuscript (in G Minor) is by Bach, and written for lute. One can see, in comparing it with the “Anna Magdalena” manuscript of the Cello Suite in D Minor, that the two are essentially the same work, but not quite. It is instructive in looking at both of them to see how Bach adapted one from the other, the order of which we cannot be sure, though my guess is that it was taken and elaborated from the BWV 1011 Cello Suite. It can serve as a model for transcribers on how to adopt Bach’s solo works to the lute. Likewise BWV 1006a, found in autograph for violin (BWV 1006) in E Major, though Egüez brings it up to F Major because of the extreme complexity of E Major for the lute.

The Partita in C Minor (BWV 997) is one of the standards found on most recordings, found in a French tablature made by Johann Christian Weyrauch, though he transcribed only the prelude, sarabande, and the giga, possibly because in keeping with the original key of D Minor he would have had to use particularly high positions. Egüez adds the chromatic fugue and the double of the giga back again. BWV 1001 is the First Suite for Solo Violin with the fuga from another source tablature (again by Weyrauch) and also used by Bach for organ as well (BWV 539). The concluding first movement of Suite No. 1 for Cello in G Major is taken from the Anna Magdalena manuscript.

Egüez has gone to great lengths to give us what must be regarded as the most “authentic” version of this music recorded, though that does not mean that we must dismiss the many and varied programs already set to disc. Most of this music is being recorded by guitarists today, and that is a shame, for when one hears the delightfully resonant and wonderfully nuanced articulations of Egüez’s 13-course lute, one gets a sampling of the extraordinary textures and colors that must have beguiled so sonic-sensitive a composer as Bach. Technically, these are without flaw, lusciously recorded with a terrific aural spread of great depth. These issues are not new; Fanfare somehow missed them upon initial release (2000 and 2002) and one hopes this review will make up for that oversight. This is mandatory for all lovers of Bach, the lute, or both. -- Steven E. Ritter

What Egüez has done is to give us those works that are substantially sustainable in the idea of actually having been played on the lute. Speculation as to how many of Bach’s works ended up being played on the instrument is of course pointless and to a certain degree impossible to determine. His selection of the specific works on these two discs comes with a reasonable assumption of the notes having actually graced lute strings. One of false assumptions is that any work determined to have been played on an instrument called the Lautenwerk might have made its way to the lute proper. This instrument, a keyboard mechanism that used gut strings and was noted for its formidable dynamic range, was developed in great part by Bach himself, but, according to contemporaries, sounded more like a theorbo than a lute. The usually included BWV 996 is omitted in this collection because the only thing that this work really has in common with a lute is the word “Lautenwerck” in the copy manuscript by (possibly) Johann Tobias Krebs. Otherwise, according to Egüez, “the extension of registry and density of counterpoint in some way exceed the adaptation possibilities of the piece to any type of lute (at least those currently known).”

Yet we know that Bach had connections with the great lutenist Silvius Weiss, for whom he may have composed the Prelude, Fugue, and Allegro, BWV 998, and the manuscript is Bach’s. So the lute was definitely within his purview, even if we cannot be sure which pieces fit the mold. The sourcing may be unreliable—and we still don’t know if or how well Bach may have played the instrument—but the existence of the lute in his circle or that of his students is without question.

BVW 995 is of especial interest since the manuscript (in G Minor) is by Bach, and written for lute. One can see, in comparing it with the “Anna Magdalena” manuscript of the Cello Suite in D Minor, that the two are essentially the same work, but not quite. It is instructive in looking at both of them to see how Bach adapted one from the other, the order of which we cannot be sure, though my guess is that it was taken and elaborated from the BWV 1011 Cello Suite. It can serve as a model for transcribers on how to adopt Bach’s solo works to the lute. Likewise BWV 1006a, found in autograph for violin (BWV 1006) in E Major, though Egüez brings it up to F Major because of the extreme complexity of E Major for the lute.

The Partita in C Minor (BWV 997) is one of the standards found on most recordings, found in a French tablature made by Johann Christian Weyrauch, though he transcribed only the prelude, sarabande, and the giga, possibly because in keeping with the original key of D Minor he would have had to use particularly high positions. Egüez adds the chromatic fugue and the double of the giga back again. BWV 1001 is the First Suite for Solo Violin with the fuga from another source tablature (again by Weyrauch) and also used by Bach for organ as well (BWV 539). The concluding first movement of Suite No. 1 for Cello in G Major is taken from the Anna Magdalena manuscript.

Egüez has gone to great lengths to give us what must be regarded as the most “authentic” version of this music recorded, though that does not mean that we must dismiss the many and varied programs already set to disc. Most of this music is being recorded by guitarists today, and that is a shame, for when one hears the delightfully resonant and wonderfully nuanced articulations of Egüez’s 13-course lute, one gets a sampling of the extraordinary textures and colors that must have beguiled so sonic-sensitive a composer as Bach. Technically, these are without flaw, lusciously recorded with a terrific aural spread of great depth. These issues are not new; Fanfare somehow missed them upon initial release (2000 and 2002) and one hopes this review will make up for that oversight. This is mandatory for all lovers of Bach, the lute, or both. -- Steven E. Ritter