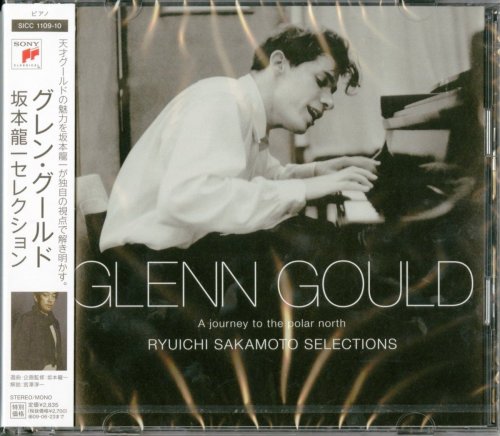

Glenn Gould - A Journey to the Polar North (Ryuichi Sakamoto Selections) (2008)

Artist: Glenn Gould

Title: A Journey to the Polar North (Ryuichi Sakamoto Selections)

Year Of Release: 2008

Label: Sony Music

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks + .cue)

Total Time: 2:03:28

Total Size: 504 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: A Journey to the Polar North (Ryuichi Sakamoto Selections)

Year Of Release: 2008

Label: Sony Music

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks + .cue)

Total Time: 2:03:28

Total Size: 504 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

CD 1

01. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.30 in E major, Op.109: I. Vivace, ma non troppo (3:17)

02. Berg: Piano Sonata No.1 (13:01)

03. Brahms: Intermezzo in E-flat major, Op.117 No.1 (5:36)

04. Brahms: Intermezzo in B-flat minor, Op.117 No.2 (5:32)

05. Brahms: Intermezzo in B minor, Op.119 No.1 (2:28)

Webern: Variations for Piano, Op.27

06. I. (1:31)

07. II. (0:33)

08. III. (3:05)

09. Shoenberg: Five Piano Pieces, Op.23: V. Walzer (2:54)

Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.8 in C minor, Op.13 "Pathetique"

10. I. Grave - Allegro di molto e con brio (6:06)

11. II. Adagio cantabile (4:46)

12. Byrd: First Pavan and Galliard (7:15)

13. Scriabin: Piano Sonata No.3 in F-sharp minor, Op.23: I. Dramatico (8:03)

CD 2

01. C.P.E. Bach: Wurttermberg Sonata No.1 in A minor, Wq.49 No.1 (H.30): III. Allegro assai (4:25)

02. Schoenberg: Eight Songs, Op.6: II. "Alles" (3:00)

03. Schumann: Quartet for Piano, Violin, Viola & Cello in E-flat major, Op.47: III. Andante cantabile (8:04)

04. Mozart: Piano Sonata No.8 in A minor, K.310 (300d): II. Andante cantabile con espressione (6:21)

05. Mozart: Piano Sonata No.11 in A major, K.331 (300i): III. Alla Turca: Allegretto (4:08)

06. Grieg: Piano Sonata in E minor, Op.7: I. Allegro moderato (6:40)

07. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.17 in D minor, Op.31 No.2 'The Tempest': III. Allegretto (4:38)

Scriabin: Two Pieces, Op.57

08. I. (1:57)

09. II. (2:32)

10. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.1 in F minor, Op.2 No.1: I. Allegro (3:58)

11. Sibelius: Piano Sonata No.1 in F-Sharp minor, Op.67 No.1: III. Allegro moderato (1:41)

Hindemith: Das Marienleben for Soprano & Piano, Op.27

12. "Geburt Maria" (3:52)

13. "Stillung Maria mit dem Auferstandenen" (3:13)

14. Bach: Concerto in D minor after Alessandro Marcello, BWV974: II. Adagio (4:49)

The defining moment of Glenn Gould's career came in 1964 when, at the age of 31, he withdrew from all public performance. The move was viewed by audiences and critics as willful and bewildering, and was seen as evidence that despite his demonstrably supreme artistry he was, in the argot of the common man, a nut.

But, as George Szell once said of him, "That nut [was] a genius." In his short international career, which spanned only 24 years, Glenn Gould changed the way the music world thought about performance practice, recording, and the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Glenn Gould was born to comfortable middle-class parents in Toronto in 1932. A pampered only child, Gould demonstrated his remarkable talents quite early and in 1943 entered the Toronto Conservatory of Music, where he quickly came to the attention of its director, Sir Ernest MacMillan. On MacMillan's recommendation, Gould was taken on as a student by the Chilean-born pedagogue Alberto Guerrero, whose own style was partly the basis for Gould's own sensitive touch. Gould once described Guerrero's keyboard technique as not so much striking the keys as "pulling them down." The other influence on Gould's technique was his experience playing the organ, wherein the tracker action is particularly responsive to variations in finger pressure.

Gould made his debut at the age of 16, playing Beethoven's fourth piano concerto in Toronto. He followed this triumph with tours across Canada and frequent broadcast performances over the CBC, introducing him to the studio enviroment which would remain a focus of his life thereafter. Gould leaped into international acclaim, in fact, through a studio production: his now-legendary 1955 Columbia Masterworks recording of Bach's Goldberg Variations. This recording, which has never been out of print in the 50 years since its first release, established Gould as a performer who combined penetrating insight (his Goldberg Variations was nothing short of a complete rethinking of the piece) and artistic daring with daunting technical prowess.

Gould's immediate fame brought international demand, and he responded with worldwide concert appearances; he met these with considerable reluctance, however, and quickly gained a reputation for last-minute cancellations. His dislike of performing in public, of being "looked at" by audiences, allowed a natural tendency of hypochondria to blossom (it was a convenient cancellation excuse), and he soon became the habitue of specialists ranging from chiropractors to psychiatrists. Long before quitting the stage forever, Gould had made frequent threats to do so, so that his 1964 decision was no surprise to those who knew him.

Following his withdrawal, Gould threw himself into a frenzy of recording, writing, and radio documentary production. His method of splicing together single performances from dozens of takes was initially viewed as something of an artistic fraud, though the technique was eventually adopted, in less exhaustive form, by the recording industry in subsequent years. His radio documentaries were less successful: a trilogy about life in Canada's northern territories combined multiple interviews in contrapuntal ways, an interesting idea that nevertheless rendered the sense of what was being said more or less unintelligible.

Though plagued by many imaginary maladies, Gould suffered from a very real hypertension that eventually led to a massive stroke, which he suffered in 1982, and from which he never recovered. He died in Toronto General Hospital, one week after being stricken, on October 4, 1982, at age 50. -- Mark Satola

But, as George Szell once said of him, "That nut [was] a genius." In his short international career, which spanned only 24 years, Glenn Gould changed the way the music world thought about performance practice, recording, and the music of Johann Sebastian Bach.

Glenn Gould was born to comfortable middle-class parents in Toronto in 1932. A pampered only child, Gould demonstrated his remarkable talents quite early and in 1943 entered the Toronto Conservatory of Music, where he quickly came to the attention of its director, Sir Ernest MacMillan. On MacMillan's recommendation, Gould was taken on as a student by the Chilean-born pedagogue Alberto Guerrero, whose own style was partly the basis for Gould's own sensitive touch. Gould once described Guerrero's keyboard technique as not so much striking the keys as "pulling them down." The other influence on Gould's technique was his experience playing the organ, wherein the tracker action is particularly responsive to variations in finger pressure.

Gould made his debut at the age of 16, playing Beethoven's fourth piano concerto in Toronto. He followed this triumph with tours across Canada and frequent broadcast performances over the CBC, introducing him to the studio enviroment which would remain a focus of his life thereafter. Gould leaped into international acclaim, in fact, through a studio production: his now-legendary 1955 Columbia Masterworks recording of Bach's Goldberg Variations. This recording, which has never been out of print in the 50 years since its first release, established Gould as a performer who combined penetrating insight (his Goldberg Variations was nothing short of a complete rethinking of the piece) and artistic daring with daunting technical prowess.

Gould's immediate fame brought international demand, and he responded with worldwide concert appearances; he met these with considerable reluctance, however, and quickly gained a reputation for last-minute cancellations. His dislike of performing in public, of being "looked at" by audiences, allowed a natural tendency of hypochondria to blossom (it was a convenient cancellation excuse), and he soon became the habitue of specialists ranging from chiropractors to psychiatrists. Long before quitting the stage forever, Gould had made frequent threats to do so, so that his 1964 decision was no surprise to those who knew him.

Following his withdrawal, Gould threw himself into a frenzy of recording, writing, and radio documentary production. His method of splicing together single performances from dozens of takes was initially viewed as something of an artistic fraud, though the technique was eventually adopted, in less exhaustive form, by the recording industry in subsequent years. His radio documentaries were less successful: a trilogy about life in Canada's northern territories combined multiple interviews in contrapuntal ways, an interesting idea that nevertheless rendered the sense of what was being said more or less unintelligible.

Though plagued by many imaginary maladies, Gould suffered from a very real hypertension that eventually led to a massive stroke, which he suffered in 1982, and from which he never recovered. He died in Toronto General Hospital, one week after being stricken, on October 4, 1982, at age 50. -- Mark Satola

![Orchestra of the Upper Atmosphere - Theta Seven (2026) [Hi-Res] Orchestra of the Upper Atmosphere - Theta Seven (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/11/jvowq9y359p2p8nxadl42bkes.jpg)

![Natalie Duncan - Black Moon (2026) [Hi-Res] Natalie Duncan - Black Moon (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1773103343_b23479te9yvqr_600.jpg)