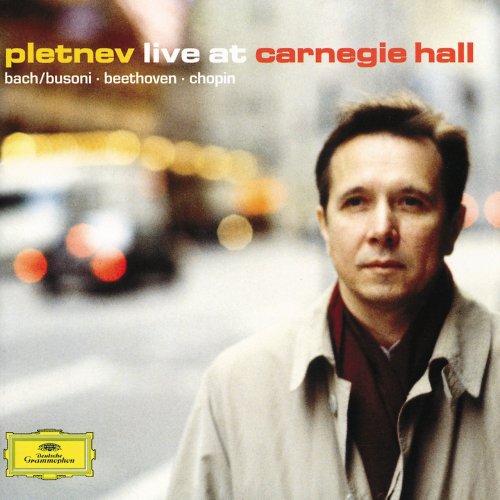

Mikhail Pletnev - Live at Carnegie Hall (2001)

Artist: Mikhail Pletnev

Title: Live at Carnegie Hall

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:42:02

Total Size: 390 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Live at Carnegie Hall

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:42:02

Total Size: 390 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

CD 1

1. J.S. Bach: Partita for Violin Solo No.2 in D minor, BWV 1004 - Chaconne in D minor

2. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.32 in C minor, Op.111 - 1. Maestoso - Allegro con brio ed appassionato

3. Beethoven: Piano Sonata No.32 in C minor, Op.111 - 2. Arietta (Adagio molto semplice e cantabile)

4. Chopin: Scherzo No.1 in B minor, Op.20

5. Chopin: Scherzo No.2 in B flat minor, Op.31

6. Chopin: Scherzo No.3 in C sharp minor, Op.39

7. Chopin: Scherzo No.4 in E, Op.54

CD 2

1. Rachmaninov: Etude-Tableau in E flat minor, Op.39, No.5 - Appassionato

2. Scriabin: 2 Poèmes, Op.32 - 1. Poème in F sharp

3. Scarlatti: Sonata in D minor, K.9

4. Moszkowski: Etude in F major, op.72, no.6 - Presto

5. Balakirev: Islamey - Presto con fuoco

Mikhail Pletnev, piano

The billed recital was the Bach-Busoni transcription, the Beethoven Sonata Op 111 and the Chopin Scherzos, and the rest – five items on a ‘bonus’ CD, finishing with Balakirev’s Islamey – amount nearly to a half-programme on top. The recording comes with buckets of applause, linking every item, and by the end of Islamey the audience is in a state of near frenzy (and the piano beginning to complain). What an awful programme, I had thought, sniffily, walking by Carnegie Hall a few days before, though had I been staying longer I would probably have gone. I blow hot and cold over Pletnev but he is not to be missed. As celebrity recitals go this must have been an exceptional spectacle. There is an old-time feel about it, as if Horowitz might have been about to walk out on stage. Bach, Beethoven, Chopin and a few others are of the party but it is the pianist people have come to hear, and they are expecting to be astonished.

An acquaintance of mine once asked a celebrated virtuoso (better nameless) why he had played something so fast. ‘Because I can,’ was the reply. When covering the ground in such thoroughbred style, Pletnev’s athleticism has an allure which is a pleasure in itself. The tumultuous codas of Chopin’s Scherzos are meat and drink to him, and in making a dash for home, over hedge and ditch, there is never a doubt about his stamina. It is a thrilling dash too, the mechanics of piano playing thrown off, the virtuosity transcendental – and the house brought down (four times). There has been grace along the way, many special moments, and always a faultless sense of timing. But with Pletnev in this mood the personality does seem disappointingly limited. It is the devil in his make-up who predominates, and you don’t have to travel far in the first Scherzo, I think, to find yourself questioning the volatility and the exaggerated feverishness of it all. Is there nothing more to these wonderful pieces than tempests, and charm and coquettishness in the slower bits? Does the middle section of the first one – folk-like and remote – really have to be perfumed to high heaven? But that is his way: toy with the detail and then snatch it away, play with the line and texture to see what novelties one might come up with, hold up the flow, if fancy invites, or perhaps step on the gas. Add a gloss, in other words, as if this constantly performed music could not be interesting to modern listeners unless given a new slant, or a wholesale transcription. It’s a point of view, I suppose, but as Pletnev takes us with him through the flea-markets I ask myself: if the operation has to be done, could there not be more authenticity of feeling and less vulgarity?

In Chopin he strikes me as a heartless fellow and I much prefer him in Beethoven. It is a traversal rather than a completely coherent interpretation of the last Sonata he offers, but it is full of striking things. The first movement alternates agitation with near-stasis, and the coda is floated away like something out of Medtner; but the spirit of inquiry and control of mass and sonority are of such an order that the ground is made fertile, the communication fresh. What Beethoven would have thought at having so many of his indications and inflections of expression stood on their heads we shan’t know, but I doubt he would have considered it a futile endeavour for the performer to take delight in the physical challenges and to allow the sense to emerge from the sound. The Arietta, played very slowly, is ideally hymn-like and direct; and although some of the detailing in the variations strikes me as weird, the breath of the huge second movement as a lyrical span is impressively sustained, right through to the final trilling, which is wonderful. Not a monumental version of the Sonata entirely hewn from the rock, then, and that makes a nice change.

The Bach-Busoni at the beginning, an uncharacteristically misguided transcription and such a waste of time, will not disappoint admirers of it. Rather give me the Scriabin, Moszkowski and Balakirev, any day, which are outstanding among the encores. Oh yes, a Carnegie Hall debut with attitude and knobs on, and no, it is never dull.

An acquaintance of mine once asked a celebrated virtuoso (better nameless) why he had played something so fast. ‘Because I can,’ was the reply. When covering the ground in such thoroughbred style, Pletnev’s athleticism has an allure which is a pleasure in itself. The tumultuous codas of Chopin’s Scherzos are meat and drink to him, and in making a dash for home, over hedge and ditch, there is never a doubt about his stamina. It is a thrilling dash too, the mechanics of piano playing thrown off, the virtuosity transcendental – and the house brought down (four times). There has been grace along the way, many special moments, and always a faultless sense of timing. But with Pletnev in this mood the personality does seem disappointingly limited. It is the devil in his make-up who predominates, and you don’t have to travel far in the first Scherzo, I think, to find yourself questioning the volatility and the exaggerated feverishness of it all. Is there nothing more to these wonderful pieces than tempests, and charm and coquettishness in the slower bits? Does the middle section of the first one – folk-like and remote – really have to be perfumed to high heaven? But that is his way: toy with the detail and then snatch it away, play with the line and texture to see what novelties one might come up with, hold up the flow, if fancy invites, or perhaps step on the gas. Add a gloss, in other words, as if this constantly performed music could not be interesting to modern listeners unless given a new slant, or a wholesale transcription. It’s a point of view, I suppose, but as Pletnev takes us with him through the flea-markets I ask myself: if the operation has to be done, could there not be more authenticity of feeling and less vulgarity?

In Chopin he strikes me as a heartless fellow and I much prefer him in Beethoven. It is a traversal rather than a completely coherent interpretation of the last Sonata he offers, but it is full of striking things. The first movement alternates agitation with near-stasis, and the coda is floated away like something out of Medtner; but the spirit of inquiry and control of mass and sonority are of such an order that the ground is made fertile, the communication fresh. What Beethoven would have thought at having so many of his indications and inflections of expression stood on their heads we shan’t know, but I doubt he would have considered it a futile endeavour for the performer to take delight in the physical challenges and to allow the sense to emerge from the sound. The Arietta, played very slowly, is ideally hymn-like and direct; and although some of the detailing in the variations strikes me as weird, the breath of the huge second movement as a lyrical span is impressively sustained, right through to the final trilling, which is wonderful. Not a monumental version of the Sonata entirely hewn from the rock, then, and that makes a nice change.

The Bach-Busoni at the beginning, an uncharacteristically misguided transcription and such a waste of time, will not disappoint admirers of it. Rather give me the Scriabin, Moszkowski and Balakirev, any day, which are outstanding among the encores. Oh yes, a Carnegie Hall debut with attitude and knobs on, and no, it is never dull.

![Gabriele Di Franco - The Value of Choices (2026) [Hi-Res] Gabriele Di Franco - The Value of Choices (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772720084_zi78jg17e4q61_600.jpg)

![Black Flower - Motions EP (2026) [Hi-Res] Black Flower - Motions EP (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772813045_cover.jpg)

![The Cosmic Tones Research Trio - Live at Public Records (Live) (2026) [Hi-Res] The Cosmic Tones Research Trio - Live at Public Records (Live) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/04/485z12vap32l1wvonjqhl0gyw.jpg)