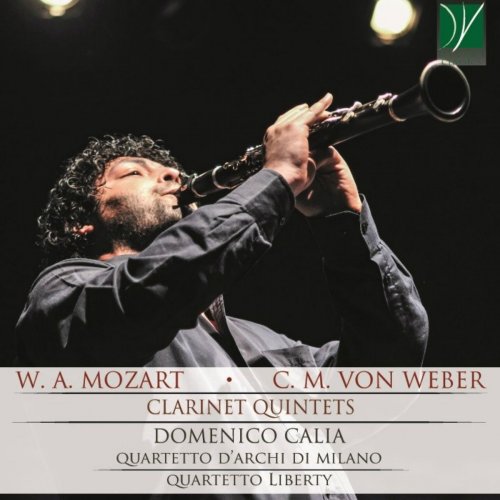

Domenico Calia - Clarinet Quintets (2019)

Artist: Domenico Calia

Title: Clarinet Quintets

Year Of Release: 2019

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 61:35 min

Total Size: 212 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Clarinet Quintets

Year Of Release: 2019

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 61:35 min

Total Size: 212 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K.581: I. Allegro

02. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K.581: II. Larghetto

03. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K.581: III. Menuetto

04. Clarinet Quintet in A Major, K.581: IV. Allegretto con variazioni

05. Clarinet Quintet in B-Flat Major, Op. 34, J. 182: I. Allegro

06. Clarinet Quintet in B-Flat Major, Op. 34, J. 182: II. Fantasia. Adagio

07. Clarinet Quintet in B-Flat Major, Op. 34, J. 182: III. Menuetto

08. Clarinet Quintet in B-Flat Major, Op. 34, J. 182: IV. Rondo. Allegro

We are so familiar with the warm and expressive tone of the clarinet and with its presence among the woodwinds of the orchestra that it may come as a surprise to realize that it is, in fact, one of the youngest members of the classical orchestra. It had, of course, a venerable ancestor in the chalumeau, a much older wind instrument, from which the clarinet borrowed the name of its own low register; but the classical clarinet entered firmly the orchestra ranks only in the eighteenth century, and did not possess a chamber music or solo literature of its own until the last decades of the century.

One of the good fortunes of the instruments was to possess a timbre which captivated the ears of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was quick to adopt its sound in many of his orchestral works, and even to rearrange some of his earlier compositions in order to find a space for its fascinating sound. Another of the clarinet’s blessings was Mozart’s meeting with Anton Stadler. Together with his brother Johann, Stadler was a member of the Emperor’s Harmonie (a wind band) and, since 1787, of the court orchestra. Mozart and Stadler were also fellow members of the freemasonry, and from their friendship flowed some of the finest works ever written for the clarinet. Both Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet KV581 and his Clarinet Concerto KV622 date from the last years of the composer’s lifetime, when he was particularly active as a freelance composer in Vienna, notably in the field of operatic music. Opera was, indeed, Mozart’s first and foremost love, and the musical qualities of his clarinet compositions seem to suggest that he conceived of this instrument as of a human voice of exceptional range and flexibility.

The clarinet is called, in fact, to showcase both its singing and cantabile qualities, and its potential for virtuoso coloratura; the close cooperation between Stadler and Mozart is revealed by the absolute mastery of the instrument’s technical features and by the adroit exploitation of its musical resources. By experimenting with Stadler, Mozart was able to develop an entirely new language for the relatively young instrument; similarly, Stadler himself was interested in technical innovations in instrument-building, and was particularly fond of a subspecies in the clarinet family, the “basset clarinet”, for which both of Mozart’s masterpieces were originally written. The basset clarinet had a lower range than its better-known counterpart, and its mellow tone undoubtedly conquered the composer’s fantasy.

Notwithstanding many evident similarities between the Quintet and the later Concerto, Mozart consciously adopted a very contrasting style for the two pieces. The Quintet is a true and masterly example of chamber music, whereby the clarinet is, at the same time, integrated within the distinctive sound of the string quartet and surrounded by it so as to reveal its most individual qualities. The string quartet, moreover, does not always act as a single being, as if a “bowed piano” would accompany a solo clarinet: instead, the individual string instruments take in turn the centre of the stage (as, for example, in the beautiful “viola” variation in the minor mode, in the last movement), sometimes in combination with the clarinet (as in the duet-like passages with the first violin in the second movement), sometimes affirming their complicity to the point of silencing the wind instrument (as happens in the first Trio of the third movement, the Menuet).

Mozart’s Quintet, which can be considered as the first masterly clarinet quintet in history, has none of the negative sides of an “experimental” work, being a fully mature and ripe masterpiece; nevertheless, it does possess all the positive aspect of experimentalism, including a freedom to explore new formal solutions even in the piece’s structure, and not only in those compositional features which are more strictly connected with the use of a new instrument or a new combination of instruments. For example, it is unusual for a Menuet to include two trios, as happens here, or for a Finale to be in the form of theme with variations. In the hands of such an experienced composer as Mozart, these experiments become as many exciting possibilities: it can be said that this Finale is in fact Mozart’s most perfect example of theme with variations. As concerns timbral exploration, instead, one of the most enchanting moments of the piece is its second movement, where a melody of unsurpassed beauty, intoned by the clarinet, is framed by the unearthly sound of the muted strings. Here the influence of the operatic language is clearly discernible, even though there is nothing “theatrical” in this piece: it is opera as the beautified and formalized outpouring of the most deeply intense, profound and sincere feelings of the human beings.

Even though the carefully crafted and continuous dialogue among the instruments qualifies this Quintet as a perfect example of “chamber” music, this did not prevent it from being successfully performed in public only a few months after its completion (September 29th, 1789), during a charity concert of the Tonkünstlerverein in Vienna a few days before Christmas, on December 22nd. The performance took place as an interlude between the two halves of a cantata by Vincenzo Righini, and, of course, the clarinet player was Stadler himself. In fact, Mozart sometimes referred to the piece as “Stadler’s Quintet”, so close was the connection between the performer who inspired the composer and the finished work.

Exactly in the same fashion, the Clarinet Quintet by Carl Maria von Weber was sometimes nicknamed “Baermann Quintet”, in homage to the clarinetist Heinrich Baermann for whom it was composed. Weber would later become one of the most successful German operatic composers in the early Romantic era: in fact, his stage works are highly indebted to Mozart’s own German operas, and particularly to the enchanted world of the Magic Flute; moreover, Weber had studied with Michael Haydn (brother of the better known Franz Joseph), who had been a close friend and cooperator of both Wolfgang and Leopold Mozart in Salzburg. There is, therefore, an almost direct artistic lineage connecting Mozart with Weber; however, in the short space of a quarter of a century, many things had changed. Weber’s Clarinet Quintet, in fact, was completed in 1815 (though the first three movements were presented to Baermann for his birthday already in 1813); the musical language, the aesthetic values and the musical scene had undergone dramatic shifts in the meanwhile, and the two works in this Da Vinci CD faithfully mirror this evolution.

The clarinet had affirmed itself as one of the protagonists in the orchestra, and had conquered a significant space also in chamber music and as a soloist. In fact, Heinrich Baermann was a touring concert musician, who sometimes could not find passable orchestras to accompany his solo concertos when he arrived in the minor centres. Thus, different from Mozart’s Quintet, Weber’s has the features of a solo concerto with miniaturized accompaniment. Here, the string quartet is less precisely characterized than in Mozart, and it has fewer occasions for displaying its own idiosyncratic qualities. On the other hand, Weber impressively succeeds in sacrificing none of the spectacular aspects of the solo/tutti opposition which characterizes a successful Concerto, and in building a piece full of variety and fantasy notwithstanding the greater homogeneity of the quartet’s sound when compared to an orchestra.

As in the case with Stadler and Mozart, also for Weber the

friendship with Baermann was crucial both for prompting the creation of the piece and for encouraging the exploration of the instrument’s full potential. Baermann was a great virtuoso, who was particularly celebrated for his smoothness in performing chromatic scales (which are, in fact, frequently found in Weber’s work); similar to Stadler, moreover, Baermann was not simply content with what the market offered him, but actively sought the latest novelties in instrument making, being justifiably proud of his 10-keyed instrument by Griesling and Schlott. From the cooperation between Baermann and Weber arose some of the benchmarks in the clarinet Romantic literature, such as the Concertino op. 26 and the two Concertos op. 73 and 74 (1811). The experience matured in these works proved very useful for the “Grand Quintet” op. 34: Weber offers the soloist the possibility of showcasing both his skill and the technical improvements in his instrument, from the very outset of the piece (where the high B flat seems to blossom from the introductory chords of the strings) to the Menuetto, where new fingering possibilities are fully exploited, to the brilliant and galvanizing passageworks and coloraturas of the Rondo.

Similar to Mozart, however, neither the technical virtuosity nor the prevailing luminous musical atmosphere prevent the composer from employing the full emotional range of the instrument’s capabilities and of the performer’s talent: in the words of a contemporaneous review, Baermann had an extraordinary tone-colour, “which has not the slightest strain or shrillness in it, both of which are so common among clarinetists”. Thus, in Weber as in Mozart, the clarinet is frequently treated as a human voice, and its darker sounds effectively contrast with the otherwise serene or vivacious mood of both works.

Taken together, as in this Da Vinci CD, these two very different and yet very connected masterpieces provide a fascinating overview on the differences and similarities between Classicism and Romanticism, between chamber and solo music, between a serene dialogue among peers and the excitement of the soloist’s heroism; they also bear witness to the power of friendship, which not only is one of the most beautiful human experiences, but also can prompt the creation of such extraordinary masterpieces as those featured in this compilation.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

One of the good fortunes of the instruments was to possess a timbre which captivated the ears of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who was quick to adopt its sound in many of his orchestral works, and even to rearrange some of his earlier compositions in order to find a space for its fascinating sound. Another of the clarinet’s blessings was Mozart’s meeting with Anton Stadler. Together with his brother Johann, Stadler was a member of the Emperor’s Harmonie (a wind band) and, since 1787, of the court orchestra. Mozart and Stadler were also fellow members of the freemasonry, and from their friendship flowed some of the finest works ever written for the clarinet. Both Mozart’s Clarinet Quintet KV581 and his Clarinet Concerto KV622 date from the last years of the composer’s lifetime, when he was particularly active as a freelance composer in Vienna, notably in the field of operatic music. Opera was, indeed, Mozart’s first and foremost love, and the musical qualities of his clarinet compositions seem to suggest that he conceived of this instrument as of a human voice of exceptional range and flexibility.

The clarinet is called, in fact, to showcase both its singing and cantabile qualities, and its potential for virtuoso coloratura; the close cooperation between Stadler and Mozart is revealed by the absolute mastery of the instrument’s technical features and by the adroit exploitation of its musical resources. By experimenting with Stadler, Mozart was able to develop an entirely new language for the relatively young instrument; similarly, Stadler himself was interested in technical innovations in instrument-building, and was particularly fond of a subspecies in the clarinet family, the “basset clarinet”, for which both of Mozart’s masterpieces were originally written. The basset clarinet had a lower range than its better-known counterpart, and its mellow tone undoubtedly conquered the composer’s fantasy.

Notwithstanding many evident similarities between the Quintet and the later Concerto, Mozart consciously adopted a very contrasting style for the two pieces. The Quintet is a true and masterly example of chamber music, whereby the clarinet is, at the same time, integrated within the distinctive sound of the string quartet and surrounded by it so as to reveal its most individual qualities. The string quartet, moreover, does not always act as a single being, as if a “bowed piano” would accompany a solo clarinet: instead, the individual string instruments take in turn the centre of the stage (as, for example, in the beautiful “viola” variation in the minor mode, in the last movement), sometimes in combination with the clarinet (as in the duet-like passages with the first violin in the second movement), sometimes affirming their complicity to the point of silencing the wind instrument (as happens in the first Trio of the third movement, the Menuet).

Mozart’s Quintet, which can be considered as the first masterly clarinet quintet in history, has none of the negative sides of an “experimental” work, being a fully mature and ripe masterpiece; nevertheless, it does possess all the positive aspect of experimentalism, including a freedom to explore new formal solutions even in the piece’s structure, and not only in those compositional features which are more strictly connected with the use of a new instrument or a new combination of instruments. For example, it is unusual for a Menuet to include two trios, as happens here, or for a Finale to be in the form of theme with variations. In the hands of such an experienced composer as Mozart, these experiments become as many exciting possibilities: it can be said that this Finale is in fact Mozart’s most perfect example of theme with variations. As concerns timbral exploration, instead, one of the most enchanting moments of the piece is its second movement, where a melody of unsurpassed beauty, intoned by the clarinet, is framed by the unearthly sound of the muted strings. Here the influence of the operatic language is clearly discernible, even though there is nothing “theatrical” in this piece: it is opera as the beautified and formalized outpouring of the most deeply intense, profound and sincere feelings of the human beings.

Even though the carefully crafted and continuous dialogue among the instruments qualifies this Quintet as a perfect example of “chamber” music, this did not prevent it from being successfully performed in public only a few months after its completion (September 29th, 1789), during a charity concert of the Tonkünstlerverein in Vienna a few days before Christmas, on December 22nd. The performance took place as an interlude between the two halves of a cantata by Vincenzo Righini, and, of course, the clarinet player was Stadler himself. In fact, Mozart sometimes referred to the piece as “Stadler’s Quintet”, so close was the connection between the performer who inspired the composer and the finished work.

Exactly in the same fashion, the Clarinet Quintet by Carl Maria von Weber was sometimes nicknamed “Baermann Quintet”, in homage to the clarinetist Heinrich Baermann for whom it was composed. Weber would later become one of the most successful German operatic composers in the early Romantic era: in fact, his stage works are highly indebted to Mozart’s own German operas, and particularly to the enchanted world of the Magic Flute; moreover, Weber had studied with Michael Haydn (brother of the better known Franz Joseph), who had been a close friend and cooperator of both Wolfgang and Leopold Mozart in Salzburg. There is, therefore, an almost direct artistic lineage connecting Mozart with Weber; however, in the short space of a quarter of a century, many things had changed. Weber’s Clarinet Quintet, in fact, was completed in 1815 (though the first three movements were presented to Baermann for his birthday already in 1813); the musical language, the aesthetic values and the musical scene had undergone dramatic shifts in the meanwhile, and the two works in this Da Vinci CD faithfully mirror this evolution.

The clarinet had affirmed itself as one of the protagonists in the orchestra, and had conquered a significant space also in chamber music and as a soloist. In fact, Heinrich Baermann was a touring concert musician, who sometimes could not find passable orchestras to accompany his solo concertos when he arrived in the minor centres. Thus, different from Mozart’s Quintet, Weber’s has the features of a solo concerto with miniaturized accompaniment. Here, the string quartet is less precisely characterized than in Mozart, and it has fewer occasions for displaying its own idiosyncratic qualities. On the other hand, Weber impressively succeeds in sacrificing none of the spectacular aspects of the solo/tutti opposition which characterizes a successful Concerto, and in building a piece full of variety and fantasy notwithstanding the greater homogeneity of the quartet’s sound when compared to an orchestra.

As in the case with Stadler and Mozart, also for Weber the

friendship with Baermann was crucial both for prompting the creation of the piece and for encouraging the exploration of the instrument’s full potential. Baermann was a great virtuoso, who was particularly celebrated for his smoothness in performing chromatic scales (which are, in fact, frequently found in Weber’s work); similar to Stadler, moreover, Baermann was not simply content with what the market offered him, but actively sought the latest novelties in instrument making, being justifiably proud of his 10-keyed instrument by Griesling and Schlott. From the cooperation between Baermann and Weber arose some of the benchmarks in the clarinet Romantic literature, such as the Concertino op. 26 and the two Concertos op. 73 and 74 (1811). The experience matured in these works proved very useful for the “Grand Quintet” op. 34: Weber offers the soloist the possibility of showcasing both his skill and the technical improvements in his instrument, from the very outset of the piece (where the high B flat seems to blossom from the introductory chords of the strings) to the Menuetto, where new fingering possibilities are fully exploited, to the brilliant and galvanizing passageworks and coloraturas of the Rondo.

Similar to Mozart, however, neither the technical virtuosity nor the prevailing luminous musical atmosphere prevent the composer from employing the full emotional range of the instrument’s capabilities and of the performer’s talent: in the words of a contemporaneous review, Baermann had an extraordinary tone-colour, “which has not the slightest strain or shrillness in it, both of which are so common among clarinetists”. Thus, in Weber as in Mozart, the clarinet is frequently treated as a human voice, and its darker sounds effectively contrast with the otherwise serene or vivacious mood of both works.

Taken together, as in this Da Vinci CD, these two very different and yet very connected masterpieces provide a fascinating overview on the differences and similarities between Classicism and Romanticism, between chamber and solo music, between a serene dialogue among peers and the excitement of the soloist’s heroism; they also bear witness to the power of friendship, which not only is one of the most beautiful human experiences, but also can prompt the creation of such extraordinary masterpieces as those featured in this compilation.

Album Notes by Chiara Bertoglio

![Johnny Mathis - Sending You a Little Christmas (2013) [Hi-Res] Johnny Mathis - Sending You a Little Christmas (2013) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/23/38ptbeu2vtopjom56b48st4yc.jpg)

![Clifton Chenier - Squeezebox Boogie (1999) [Hi-Res] Clifton Chenier - Squeezebox Boogie (1999) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/20/cmlfho2wfdjon4pewnwrm16l7.jpg)

![Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden & Ed Blackwell - Old And New Dreams (1979/2025) [Hi-Res] Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Charlie Haden & Ed Blackwell - Old And New Dreams (1979/2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766322079_cover.jpg)

![Clifton Chenier - Clifton Chenier and His Red Hot Louisiana Band (1978) [Hi-Res] Clifton Chenier - Clifton Chenier and His Red Hot Louisiana Band (1978) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/20/u7c9mz3puf20w5rxo6nmae80o.jpg)