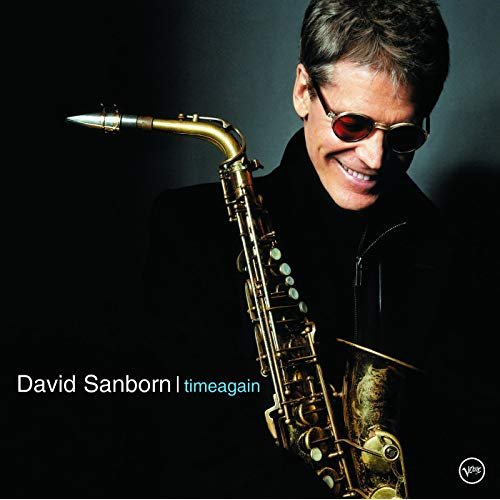

David Sanborn - Time Again (2003) Hi Res

Artist: David Sanborn

Title: Time Again

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: Decca (UMO)

Genre: Jazz

Quality: 320 kbps | FLAC (tracks) | 24Bit/96 kHz FLAC

Total Time: 00:51:44

Total Size: 116 mb | 298 mb | 1.1 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Time Again

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: Decca (UMO)

Genre: Jazz

Quality: 320 kbps | FLAC (tracks) | 24Bit/96 kHz FLAC

Total Time: 00:51:44

Total Size: 116 mb | 298 mb | 1.1 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Comin' Home Baby

02. Cristo Redentor

03. Harlem Nocturne

04. Man From Mars

05. Isn't She Lovely

06. Sugar

07. Tequila

08. Little Flower

09. Spider B.

10. Delia

Personnel:

David Sanborn, Alto Saxophone

Steve Gadd, Drums

Christian McBride, Bass

Russell Malone, Guitar (Tracks 1-7, 9, 10)

Mike Mainieri, Vibraphone (Tracks 1-4, 6-10)

Gil Goldstein, Piano (Tracks 2, 6, 9, 10)

Ricky Petersen, Keyboards & Drum Programming (Tracks 4-5, 7, 9)

Don Alias, Percussion (Tracks 1, 3-4, 6, 7)

Luis Quintero, Percussion (Tracks 3-4, 7)

Randy Brecker, Trumpet, Flugelhorn (Track 9)

Lawrence Feldman, Alto Flute, Bass Flute (Track 9)

Stewart Levine, Producer

timeagain is a refreshing musical departure for the GRAMMY-award winning recording artist, and an album that holds great personal significance. Produced by Stewart Levine (The Crusaders Rural Renewal on Verve), Sanborn likens the process of making this album to “blowing up a snapshot”. The original conceptions and arrangements were formed by David at his home studio. He then enlisted Levine’s aid to “flesh them out” bringing in an all-star cast of top flight musicians to expand upon the original demos while keeping the feel of the early versions. The core band: Christian McBride on bass, Steve Gadd on drums, Russell Malone on guitar, and Mike Manieri on vibes, create a classic ensemble sound with a live vibe. Sanborn himself has never sounded better, playing with authority, inventiveness, and heart.

David Sanborn's new album, timeagain, is not a jazz album; it's a pop-instrumental record. But that's a description, not a judgment. There are good and bad pop-instrumental albums, just as there are good and bad jazz releases; one is not automatically superior to the other.

Over his 28 years as a leader, Sanborn has proven how pop-instrumental music can be done with dignity and imagination. Because improvisation and harmonic substitution are less important in pop than they are in jazz, tone and phrasing become more important, and those are the two areas where Sanborn has always excelled.

The alto saxophonist, now 57, boasts a warm, humming timbre, but there's a hint of tartness that creates a welcome tension and prevents the gushy melodrama that afflicts so many pop horn players (and I would never be so tactless as to mention Kenny G here). Moreover, Sanborn understands that pauses are as important as notes in shaping a line, and his restraint contrasts with the busy overplaying that marks today's pop-instrumental field (aka smooth jazz).

As if to make an argument for the genre's validity, Sanborn anchors his new release with four pop-instrumental classics: the Johnny Otis Orchestra's 'Harlem Nocturne' (1945), the Champs' 'Tequila' (1958) Herbie Mann's 'Comin' Home Baby' (1961) and Stanley Turrentine's 'Sugar' (1970). To these he adds Duke Pearson's 'Cristo Redentor,' the most famous result of A New Perspective, Donald Byrd's 1963 jazz-gospel-fusion project, and Stevie Wonder's 1976 hit 'Isn't She Lovely,' a pop standard recorded by everyone from Stephane Grappelli and Milt Jackson to Keb' Mo' and James Galway.

What all six of these tunes have in common is a compact melody, usually no more than four measures, that's so infectious, so perfectly matched to its rhythm pattern, that you can't get it out of your head. Nor would you want to, for a hypnotic hook provides a pleasure you can't get enough of. So, in contrast to a jazzman who would soon leave the motif behind to improvise new harmonic structures, the pop instrumentalist keeps the theme in the foreground, making small alterations to reveal new aspects but never obscuring the essential shape of the melody.

The trick is to keep the variations frequent enough to prevent monotony but small enough to keep the hook and the groove intact. Sanborn does this as well as anyone. His saxophone seems to exult in melody; it will eagerly leap into a phrase and then hold out a climactic note, as if reluctant to let go of something that feels so good. His variations on a theme are aimed more at creating new melodies than new harmonies.

Just listen to how he attacks the two-bar hook of 'Tequila.' After planting it firmly in our brains, he finds new ending notes for each measure; then he drops half a bar by an octave; then he substitutes a new melodic detour for the first bar, retaining the second; then he inverts that approach. He keeps twisting the phrase into new melodic shapes, but he never obscures the original motif and he never loses the beat.

For Sanborn is a very rhythmic player, toughening his tone to mark the accents in a phrase and using pauses as punctuation. Even though he's the leader, he often sounds as if he's part of the album's all-star rhythm section of guitarist Russell Malone, vibist Mike Mainieri, bassist Christian McBride and drummer Steve Gadd. These jazz musicians add secondary beats to make the bottom more interesting, but like good pop musicians they never leave the primary beat implied; it's always stated quite explicitly and quite crisply.

Sanborn, producer Stewart Levine (the Crusaders) and arranger Gil Goldstein aren't averse to tampering with the arrangements of these standards: the Latin underpinnings of 'Tequila' are brought to the surface; 'Harlem Nocturne' is taken more briskly than usual; and 'Isn't She Lovely' has a dreamier, more leisurely feel. But once the format is set, it's less likely to vary than it would on a jazz project.

Some arrangements work better than others. 'Cristo Redentor' suffers from those cursed 'ghost vocals,' that gimmick of adding background vocal harmonies without a lead vocal to accompany. Sounding bland and anonymous, it's one of the worst arrangement ideas of the past 40 years. And by shifting gears too often, the band never quite nails the groove on 'Sugar.'

On the other hand, 'Comin' Home Baby' smolders like a Steely Dan track with Sanborn's alto sax phrasing like a Donald Fagen vocal. Don Alias' conga part turns 'Harlem Nocturne' into a 'Spanish Harlem Nocturne,' and Sanborn's sax maintains a film-noir cool amid the jittery energy around him. And the same horn finds new drama in the held-out notes of the slowed-down 'Isn't She Lovely'; as a single note swells, swoons and revives, the romance of Wonder's melody is more obvious than ever.

Sanborn adds three original compositions to the end of the disc. Both 'Spider B.' and 'Delia' are Sanborn's attempts to write late-night blues vamps in the style of 'Harlem Nocturne,' and while he doesn't match that classic, he comes close enough to be respectable. 'Little Flower' is a lovely ballad with a restrained rhythm section and muted strings reinforcing the tenderness of the composer's solo. Something very similar also happens on Sanborn's adaptation of the Joni Mitchell ballad 'Man From Mars.'

It would be silly to criticize timeagain for its lack of harmonic sophistication, rhythmic elasticity or conceptual innovations. Those are jazz goals. This is a pop-instrumental album that delivers in full on its promises of melodies, grooves and subtle variations. And it does so with the sort of understatement and curiosity that's all too rare in its field.

The problem with most 'smooth-jazz' records is not that they're inauthentic jazz. A lot of great music is not jazz. The problem isn't that they're bad pop-instrumental records, full of maudlin themes, robotic rhythms, empty virtuosity and a reliance on the obvious. Once again Sanborn has demonstrated how it can be done right. (Geoffrey Himes, JazzTines)

David Sanborn's new album, timeagain, is not a jazz album; it's a pop-instrumental record. But that's a description, not a judgment. There are good and bad pop-instrumental albums, just as there are good and bad jazz releases; one is not automatically superior to the other.

Over his 28 years as a leader, Sanborn has proven how pop-instrumental music can be done with dignity and imagination. Because improvisation and harmonic substitution are less important in pop than they are in jazz, tone and phrasing become more important, and those are the two areas where Sanborn has always excelled.

The alto saxophonist, now 57, boasts a warm, humming timbre, but there's a hint of tartness that creates a welcome tension and prevents the gushy melodrama that afflicts so many pop horn players (and I would never be so tactless as to mention Kenny G here). Moreover, Sanborn understands that pauses are as important as notes in shaping a line, and his restraint contrasts with the busy overplaying that marks today's pop-instrumental field (aka smooth jazz).

As if to make an argument for the genre's validity, Sanborn anchors his new release with four pop-instrumental classics: the Johnny Otis Orchestra's 'Harlem Nocturne' (1945), the Champs' 'Tequila' (1958) Herbie Mann's 'Comin' Home Baby' (1961) and Stanley Turrentine's 'Sugar' (1970). To these he adds Duke Pearson's 'Cristo Redentor,' the most famous result of A New Perspective, Donald Byrd's 1963 jazz-gospel-fusion project, and Stevie Wonder's 1976 hit 'Isn't She Lovely,' a pop standard recorded by everyone from Stephane Grappelli and Milt Jackson to Keb' Mo' and James Galway.

What all six of these tunes have in common is a compact melody, usually no more than four measures, that's so infectious, so perfectly matched to its rhythm pattern, that you can't get it out of your head. Nor would you want to, for a hypnotic hook provides a pleasure you can't get enough of. So, in contrast to a jazzman who would soon leave the motif behind to improvise new harmonic structures, the pop instrumentalist keeps the theme in the foreground, making small alterations to reveal new aspects but never obscuring the essential shape of the melody.

The trick is to keep the variations frequent enough to prevent monotony but small enough to keep the hook and the groove intact. Sanborn does this as well as anyone. His saxophone seems to exult in melody; it will eagerly leap into a phrase and then hold out a climactic note, as if reluctant to let go of something that feels so good. His variations on a theme are aimed more at creating new melodies than new harmonies.

Just listen to how he attacks the two-bar hook of 'Tequila.' After planting it firmly in our brains, he finds new ending notes for each measure; then he drops half a bar by an octave; then he substitutes a new melodic detour for the first bar, retaining the second; then he inverts that approach. He keeps twisting the phrase into new melodic shapes, but he never obscures the original motif and he never loses the beat.

For Sanborn is a very rhythmic player, toughening his tone to mark the accents in a phrase and using pauses as punctuation. Even though he's the leader, he often sounds as if he's part of the album's all-star rhythm section of guitarist Russell Malone, vibist Mike Mainieri, bassist Christian McBride and drummer Steve Gadd. These jazz musicians add secondary beats to make the bottom more interesting, but like good pop musicians they never leave the primary beat implied; it's always stated quite explicitly and quite crisply.

Sanborn, producer Stewart Levine (the Crusaders) and arranger Gil Goldstein aren't averse to tampering with the arrangements of these standards: the Latin underpinnings of 'Tequila' are brought to the surface; 'Harlem Nocturne' is taken more briskly than usual; and 'Isn't She Lovely' has a dreamier, more leisurely feel. But once the format is set, it's less likely to vary than it would on a jazz project.

Some arrangements work better than others. 'Cristo Redentor' suffers from those cursed 'ghost vocals,' that gimmick of adding background vocal harmonies without a lead vocal to accompany. Sounding bland and anonymous, it's one of the worst arrangement ideas of the past 40 years. And by shifting gears too often, the band never quite nails the groove on 'Sugar.'

On the other hand, 'Comin' Home Baby' smolders like a Steely Dan track with Sanborn's alto sax phrasing like a Donald Fagen vocal. Don Alias' conga part turns 'Harlem Nocturne' into a 'Spanish Harlem Nocturne,' and Sanborn's sax maintains a film-noir cool amid the jittery energy around him. And the same horn finds new drama in the held-out notes of the slowed-down 'Isn't She Lovely'; as a single note swells, swoons and revives, the romance of Wonder's melody is more obvious than ever.

Sanborn adds three original compositions to the end of the disc. Both 'Spider B.' and 'Delia' are Sanborn's attempts to write late-night blues vamps in the style of 'Harlem Nocturne,' and while he doesn't match that classic, he comes close enough to be respectable. 'Little Flower' is a lovely ballad with a restrained rhythm section and muted strings reinforcing the tenderness of the composer's solo. Something very similar also happens on Sanborn's adaptation of the Joni Mitchell ballad 'Man From Mars.'

It would be silly to criticize timeagain for its lack of harmonic sophistication, rhythmic elasticity or conceptual innovations. Those are jazz goals. This is a pop-instrumental album that delivers in full on its promises of melodies, grooves and subtle variations. And it does so with the sort of understatement and curiosity that's all too rare in its field.

The problem with most 'smooth-jazz' records is not that they're inauthentic jazz. A lot of great music is not jazz. The problem isn't that they're bad pop-instrumental records, full of maudlin themes, robotic rhythms, empty virtuosity and a reliance on the obvious. Once again Sanborn has demonstrated how it can be done right. (Geoffrey Himes, JazzTines)

![Acid Mothers Reynols, Acid Mothers Temple, Reynols - Vol. 3 (2024) [Hi-Res] Acid Mothers Reynols, Acid Mothers Temple, Reynols - Vol. 3 (2024) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/21/vgzin7mjpuc9xi8v2ce3z1jc8.jpg)

![Aaron Quinn - To Be Held (2026) [Hi-Res] Aaron Quinn - To Be Held (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/20/zmwyd3pc4g0fv5hzoz5kht5h3.jpg)

![Gonzalo Mazzutti - Lo que nos une (2026) [Hi-Res] Gonzalo Mazzutti - Lo que nos une (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771563491_cover.jpg)

![Susie Philipsen - Sunday Kissing Club (2026) [Hi-Res] Susie Philipsen - Sunday Kissing Club (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771738386_500x500.jpg)