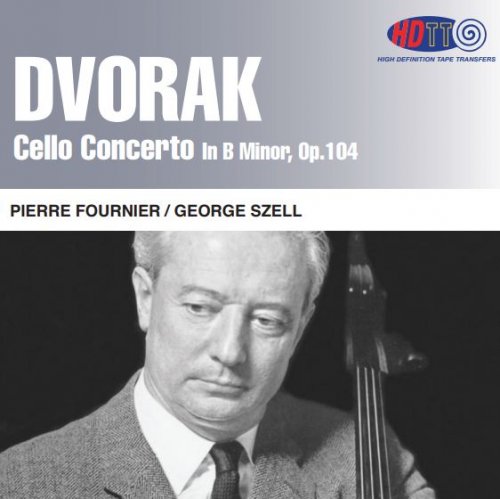

Pierre Fournier - Dvorak: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104 (2014) [DSD128 + Hi-Res]

Artist: Pierre Fournier, George Szell

Title: Dvorak: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104

Year Of Release: 1961 / 2014

Label: High Definition Tape Transfers

Genre: Classical

Quality: DSD128 (*.dsf) 5.6 MHz / 1 Bit / FLAC (tracks) [192/24]

Total Time: 38:24

Total Size: 3.03 GB / 928 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Dvorak: Cello Concerto in B Minor, Op. 104

Year Of Release: 1961 / 2014

Label: High Definition Tape Transfers

Genre: Classical

Quality: DSD128 (*.dsf) 5.6 MHz / 1 Bit / FLAC (tracks) [192/24]

Total Time: 38:24

Total Size: 3.03 GB / 928 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

1 Allegro 14:39

2 Adagio, ma non troppo 11:24

3 Finale: (Allegro moderato – Andante – Allegro vivo) 12:20

Performers:

Pierre Fournier (Cello)

George Szell

The Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra

Pierre Léon Marie Fournier was born into a military family. His father was a general; his mother was musical and taught him piano lessons. At the age of 9, he suffered a mild attack of polio. Weakness of his legs made pedaling the piano difficult. So he turned to the cello, and after making rapid progress, he was admitted to the Paris Conservatoire. His teachers there were Paul Bazelaire and Anton Hekking; he graduated in 1924 at the age of 17. Fournier made his debut the year after his graduation. This was a solo appearance with the Concerts Colonne Orchestra, which received favorable notices. The almost invariable comment in reviews was the perfection of his bowing technique. He began a successful career as a touring concert artist and as a performer in chamber music concerts, gaining a great reputation in Europe.

In 1937 to 1939, he was the director of cello studies at the Ecole Normal. It was often said that he became a friendly rival with his contemporary, cellist Paul Tortelier, and after attending a Tortelier concert remarked to him, "Paul, I wish I had your left hand." Tortelier responded, "Pierre, I wish I had your right." To Fournier, the secret of his great right hand (i.e., bowing technique) was keeping the elbow high, holding the bow firmly, but allowing the hand and arm to move fluidly. He prescribed the Sevcik violin bowing studies for his cello students.

In 1941, he became a member of the faculty at the Paris Conservatoire, but during the war years, his concert touring career was impossible. Once the war was over, though, was able to resume and he rapidly increased in fame and international stature. His old audience found that he had grown in artistic depth. Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti, meeting Fournier in rehearsals for a 1947 Edinburgh Festival appearance, had not heard him for over ten years and wrote that he was "tremendously impressed by the Apollonian beauty and poise that his playing had acquired in the intervening years. Szigeti, Fournier, violist William Primrose, and pianist Artur Schnabel formed a piano quartet in those years and gave some fabled concerts at which they played virtually all of Schubert's and Brahms' piano chamber music. Sadly, the BBC acetate air checks of this cycle were allowed to deteriorate and have been lost.

Fournier made his first U.S. tour in 1948. His chamber music partner Artur Schnabel spread the word among cellists, other musicians, and critics that they were to be visited by a great new cellist. The New York and Boston critics were ecstatic. He had to give up his Conservatoire post because of his expanding concert career; he appeared in Moscow for the first time in 1959. Commentator Lev Grinberg wrote that he was notable for a romantic interpretation; clarity of form; vivid phrasing; and clean, broad bowing all "aimed at revealing the content."

He had a broad repertoire, including Bach, Boccherini, the Romantics, Debussy, Hindemith, and Prokofiev. Composers Martinu, Martinon, Martin, Roussel, and Poulenc all wrote works for him. He had a standing Friday night date to privately play chamber music with Alfred Cortot, the eminent French pianist, at which they might be visited by musicians like Jacques Thibaud. In 1953, he became a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor and was promoted to officer in 1963.

In 1972, he retired to Switzerland and gave master classes. He still gave concerts, even as late as 1984 when he was 78, and a London critic praised the fluency of his playing and his strong and solid left-hand technique. ~ Joseph Stevenson

In 1937 to 1939, he was the director of cello studies at the Ecole Normal. It was often said that he became a friendly rival with his contemporary, cellist Paul Tortelier, and after attending a Tortelier concert remarked to him, "Paul, I wish I had your left hand." Tortelier responded, "Pierre, I wish I had your right." To Fournier, the secret of his great right hand (i.e., bowing technique) was keeping the elbow high, holding the bow firmly, but allowing the hand and arm to move fluidly. He prescribed the Sevcik violin bowing studies for his cello students.

In 1941, he became a member of the faculty at the Paris Conservatoire, but during the war years, his concert touring career was impossible. Once the war was over, though, was able to resume and he rapidly increased in fame and international stature. His old audience found that he had grown in artistic depth. Hungarian violinist Joseph Szigeti, meeting Fournier in rehearsals for a 1947 Edinburgh Festival appearance, had not heard him for over ten years and wrote that he was "tremendously impressed by the Apollonian beauty and poise that his playing had acquired in the intervening years. Szigeti, Fournier, violist William Primrose, and pianist Artur Schnabel formed a piano quartet in those years and gave some fabled concerts at which they played virtually all of Schubert's and Brahms' piano chamber music. Sadly, the BBC acetate air checks of this cycle were allowed to deteriorate and have been lost.

Fournier made his first U.S. tour in 1948. His chamber music partner Artur Schnabel spread the word among cellists, other musicians, and critics that they were to be visited by a great new cellist. The New York and Boston critics were ecstatic. He had to give up his Conservatoire post because of his expanding concert career; he appeared in Moscow for the first time in 1959. Commentator Lev Grinberg wrote that he was notable for a romantic interpretation; clarity of form; vivid phrasing; and clean, broad bowing all "aimed at revealing the content."

He had a broad repertoire, including Bach, Boccherini, the Romantics, Debussy, Hindemith, and Prokofiev. Composers Martinu, Martinon, Martin, Roussel, and Poulenc all wrote works for him. He had a standing Friday night date to privately play chamber music with Alfred Cortot, the eminent French pianist, at which they might be visited by musicians like Jacques Thibaud. In 1953, he became a Chevalier of the Legion of Honor and was promoted to officer in 1963.

In 1972, he retired to Switzerland and gave master classes. He still gave concerts, even as late as 1984 when he was 78, and a London critic praised the fluency of his playing and his strong and solid left-hand technique. ~ Joseph Stevenson

![Pasquale Cataldi - Maybe (2026) [Hi-Res] Pasquale Cataldi - Maybe (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771154794_shtkhljffl929_600.jpg)

![Jon Henriksson, Pelle von Bülow, Rasmus Holm - Monkurt (2026) [Hi-Res] Jon Henriksson, Pelle von Bülow, Rasmus Holm - Monkurt (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/15/ja2eavgnqk7dn4c3l9myzfk37.jpg)

![Katrine Schmidt - Wearing My Heart On My Sleeve (2026) [Hi-Res] Katrine Schmidt - Wearing My Heart On My Sleeve (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771145515_ugcrf0sr2pkvk_600.jpg)