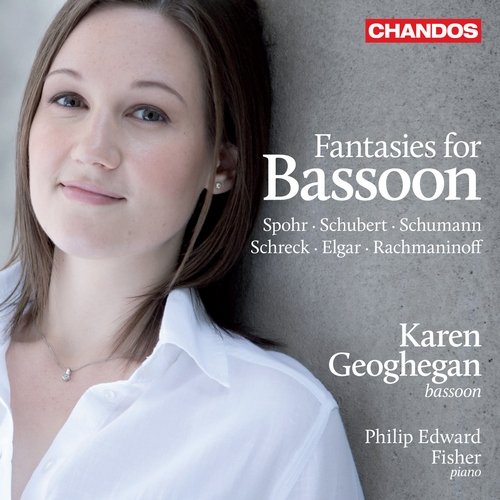

Karen Geoghegan, Philip Edward Fisher - Fantasies for Bassoon: Spohr, Schubert, Schumann, Schreck, Elgar, Rachmaninoff (2011)

Artist: Karen Geoghegan, Philip Edward Fisher

Title: Fantasies for Bassoon: Spohr, Schubert, Schumann, Schreck, Elgar, Rachmaninoff

Year Of Release: 2011

Label: Chandos

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:06:45

Total Size: 243 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Fantasies for Bassoon: Spohr, Schubert, Schumann, Schreck, Elgar, Rachmaninoff

Year Of Release: 2011

Label: Chandos

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:06:45

Total Size: 243 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Franz Schubert (1797 – 1828)

[1]-[3] Sonata in A minor, D 821 ‘Arpeggione’

Arrangement based on version by Bernhard Günther for cello and piano of Sonata for arpeggione and piano

Сергей Рахманинов (1873 – 1943)

[4] Vocalise

Arrangement based on version edited by Raphael Wallfisch for cello and piano

Gustav Schreck (1849 – 1918)

[5]-[7] Sonata in E flat major, Op. 9

Louis Spohr (1784 – 1859)

[8] Adagio in F major

Sir Edward Elgar (1857 – 1934)

[9] Salut d’amour, Op. 12

Arrangement based on version by the composer for cello and piano

Robert Schumann (1810 – 1856)

[10]-[12] Fantasiestücke, Op. 73

Arrangement based on version by Friedrich Grützmacher (1832 – 1903) for cello and piano

Personnel:

Karen Geoghegan - bassoon

Philip Edward Fisher - piano

Bassoonist Karen Geoghegan is new to me, but I see she’s recorded five other discs for Chandos, as well as embarking on a busy concert career. As for her pianist, Philip Edward Fisher, he’s perhaps better known as a concert soloist than as an accompanist, although it doesn’t take long to realise he’s a most thoughtful and discreet partner; only once or twice does he draw attention to himself – quite legitimately, I hasten to add – with some bravura playing. And a quick sample of this CD suggests the sound is well up to the standards of the house. Factor in exhaustive – but very readable – liner-notes and you have a good quality package that promises much.

This talented duo certainly deliver, with a range of works adapted for bassoon and piano; only the Schreck sonata was written for this pairing. Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata – its subtitle derives from the short-lived cello-guitar hybrid for which it was intended – is a most attractive opener. After Fisher’s warm, lyrical introduction Geoghegan’s firm, well-rounded tones are an absolute delight. Articulation is precise, and her playing is full of character and strength; her long, liquid lines are especially alluring. Fisher acquits himself well too, the balance between piano and bassoon entirely natural.

The programme is well chosen with Rachmaninov’s highly wrought Vocalise shifting to the bassoon’s higher registers. That said, there’s no hint of pinched tone and Geoghegan very much in control of the instrument. By contrast, the Schreck piece seems to offer the best of both worlds, combining lyricism with a darkly tempestuous piano part. This is one instance where the focus shifts away from the bassoon; but there’s no sense that Fisher is grandstanding, for Schreck’s writing is pretty florid anyway. It’s still a well-behaved partnership. The music-making is both easeful and eloquent; in short, an ideal combination of virtues.

After all that Sturm und Drang the more classically-shaped Adagio by Spohr – an arrangement of the slow movement of his Sonata concertante, Op. 115, for violin and harp – offers some respite. Geoghegan’s sustained notes and trills are always assured and the velvet tactility of her bassoon is very well caught by the Chandos team. This is easy listening in the very best sense, of relaxing in the company of fine musicians out to beguile and entertain, which they do in equal measure. There’s a delightful buoyancy to Salut d’amour. The strength and individuality of the players ensures that one stays engaged to the very end. Indeed, the rapt close of the Elgar is simply ravishing. I found myself making liberal use of the repeat button. It really isn’t hard to see why Geoghegan has won so many distinguished prizes, for this is playing of an exalted order.

The disc rounds off with a broad, passionate account of the Schumann Fantasiestücke. In this both players are at their rippling, surging best. Once again Fisher makes the most of his emphatically written part, giving a tantalising glimpse of his power as a soloist. For much of this piece I was reminded of Gerald Moore’s lieder accompaniment which, while mostly a model of discretion, is apt to astound with its unexpected insights.

This talented duo certainly deliver, with a range of works adapted for bassoon and piano; only the Schreck sonata was written for this pairing. Schubert’s Arpeggione Sonata – its subtitle derives from the short-lived cello-guitar hybrid for which it was intended – is a most attractive opener. After Fisher’s warm, lyrical introduction Geoghegan’s firm, well-rounded tones are an absolute delight. Articulation is precise, and her playing is full of character and strength; her long, liquid lines are especially alluring. Fisher acquits himself well too, the balance between piano and bassoon entirely natural.

The programme is well chosen with Rachmaninov’s highly wrought Vocalise shifting to the bassoon’s higher registers. That said, there’s no hint of pinched tone and Geoghegan very much in control of the instrument. By contrast, the Schreck piece seems to offer the best of both worlds, combining lyricism with a darkly tempestuous piano part. This is one instance where the focus shifts away from the bassoon; but there’s no sense that Fisher is grandstanding, for Schreck’s writing is pretty florid anyway. It’s still a well-behaved partnership. The music-making is both easeful and eloquent; in short, an ideal combination of virtues.

After all that Sturm und Drang the more classically-shaped Adagio by Spohr – an arrangement of the slow movement of his Sonata concertante, Op. 115, for violin and harp – offers some respite. Geoghegan’s sustained notes and trills are always assured and the velvet tactility of her bassoon is very well caught by the Chandos team. This is easy listening in the very best sense, of relaxing in the company of fine musicians out to beguile and entertain, which they do in equal measure. There’s a delightful buoyancy to Salut d’amour. The strength and individuality of the players ensures that one stays engaged to the very end. Indeed, the rapt close of the Elgar is simply ravishing. I found myself making liberal use of the repeat button. It really isn’t hard to see why Geoghegan has won so many distinguished prizes, for this is playing of an exalted order.

The disc rounds off with a broad, passionate account of the Schumann Fantasiestücke. In this both players are at their rippling, surging best. Once again Fisher makes the most of his emphatically written part, giving a tantalising glimpse of his power as a soloist. For much of this piece I was reminded of Gerald Moore’s lieder accompaniment which, while mostly a model of discretion, is apt to astound with its unexpected insights.

![Roberta Flack - Roberta Flack (2026 Remaster) [Hi-Res] Roberta Flack - Roberta Flack (2026 Remaster) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1772098000_cover.png)

![Larry Coryell - Major Jazz Minor Blues (1998) [CDRip] Larry Coryell - Major Jazz Minor Blues (1998) [CDRip]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771860317_5.jpg)