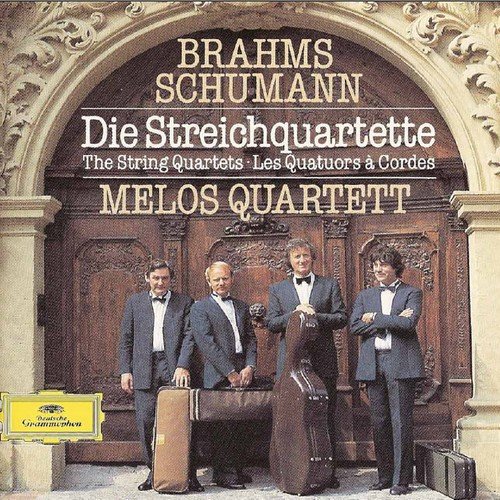

Melos Quartet - Brahms & Schumann - The String Quartets (1988)

Artist: Melos Quartet

Title: Brahms & Schumann - The String Quartets

Year Of Release: 1988 (2007)

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: APE (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 02:57:23

Total Size: 932 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Brahms & Schumann - The String Quartets

Year Of Release: 1988 (2007)

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: APE (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 02:57:23

Total Size: 932 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

CD 1:

01 Schumann - Quartet in a minor op.41 No.1 - I. Introduzione. Andante espressivo - Allegro

02 II. Scherzo, Presto-Intermezzo

03 III. Adagio

04 IV. Presto

05 Schumann - Quartet in F Major op.41 No.2 - I. Allegro vivace

06 II. Andante, quasi Variazioni

07 III. Scherzo Presto

08 IV. Allegro molto vivace

CD 2:

01 Schumann - Quartet in A major op.41 no. 3 - I. Andante espressivo - Allegro molto moderato

02 II. Assai agitato - Un poco Adagio - Tempro risoluto

03 III. Adagio molto

04 IV. Finale, Allegro molto vivace

05 Brahms - Quartet in B major op. 67 - I. Vivace

06 II. Andante

07 III. Agiato (Allegretto non troppo) - Trio - Coda

08 IV. Poco Allegretto con Variazioni

CD 3:

01 Brahms - Quartet in c minor op.51 No.1 - I. Allegro

02 II. Romanze. Poco Adagio

03 III. Allegretto molto moderato e comodo - Un poco piu animato

04 IV. Allegro

05 Brahms - Quartet in a minor op.51 No.2 - I. Allegro non troppo

06 II. Andante moderato

07 III. Quasi Menuetto, moderato - Allegretto vivace

08 IV. Finale. Allegro non assai

Performers:

Melos Quartet

Wilhelm Melcher

Gerhard Voss

Peter Buck

Hermann Voss

Apart from the Takacs Quartet, whose spirited, youthful account for Hungaroton/Conifer (4/88) of Schumann's three quartets was marred by inferior recorded sound, no single group has as yet given us either a complete Schumann or Brahms quartet cycle on CD—and certainly not a composite set of all six works. So all gratitude to the Melos Quartet for filling the gap. Their playing is immediately enjoyable for its warmth, its rhythmic impulse and its very positive directness. To try and place it in sharper perspective I've nevertheless taken the liberty of comparing the two discs with my cherished old LP set of the same works from the Quartetto Italiano (Philips—nla). For even though this has recently been deleted, I wouldn't be at all surprised to find it back in the shops, digitally remastered, before too long.

Perhaps the essential stylistic difference is that the Germans make their points more urgently and assertively, the Italians with more yielding persuasion, as the slow introduction to Schumann's A minor First Quartet, taken faster and more straightforwardly by the Melos, at once makes clear. In the F major Second Quartet the German speeds are in fact marginally slower than those of the Italians (here at their most mercurial). But in general it's nearly always the Italians who allow just a little more time for the music to breathe, and for themselves to enjoy a few more subtleties of melodic grace, textural balance and tonal refinement. As the more feminine of the two composers, I think it is Schumann who most benefits from the tenderer Italian approach, not least in the cajoling lyricism of the Third Quartet in A major. The Melos, with their pungent accentuation, are of course splendid in the tempo risoluto variation of its second movement and in the dancing finale, just as they are in the exuberant vitality of the First Quartet's concluding Presto.

In his own First Quartet in C minor, the 40-year-old Brahms makes scarcely less dramatic a challenge than in the symphony in that key so soon to follow—that's to say in its two flanking movements. Here the Melos players are really in their element, projecting the music at the highest imaginable voltage in comparison with what I can only describe as the inner intensity of their rivals. In the Romanze it is the Italians who again give themselves just a bit more time to prise out inner secrets—with more sensitively accented detail in the dolce second subject. Honours are fairly equally divided in the A minor work, with the Melos perhaps the winners in extrovert rhythmic vitality (not least in the finale) and the Italians, again, in subtleties of phrasing. That is scarcely less true of the Third B flat Quartet, where the Melos make their points without unspecified yieldings of pulse or changes of tempo. In the final variations, for instance, their presentation of the theme may lack the charm of their rivals. But they don't take the liberty of transforming the wonderful molto dolce variation in G flat into a quasi slow movement.

The new recording is forward and vivid. Some people may prefer its vibrant brightness to the mellower, finger-grained Philips sound. For my own part I think it would still be the Italians who'd come with me to my desert island. But let me repeat: the German issue has virtues of its own that could win both composers many new friends.'

Perhaps the essential stylistic difference is that the Germans make their points more urgently and assertively, the Italians with more yielding persuasion, as the slow introduction to Schumann's A minor First Quartet, taken faster and more straightforwardly by the Melos, at once makes clear. In the F major Second Quartet the German speeds are in fact marginally slower than those of the Italians (here at their most mercurial). But in general it's nearly always the Italians who allow just a little more time for the music to breathe, and for themselves to enjoy a few more subtleties of melodic grace, textural balance and tonal refinement. As the more feminine of the two composers, I think it is Schumann who most benefits from the tenderer Italian approach, not least in the cajoling lyricism of the Third Quartet in A major. The Melos, with their pungent accentuation, are of course splendid in the tempo risoluto variation of its second movement and in the dancing finale, just as they are in the exuberant vitality of the First Quartet's concluding Presto.

In his own First Quartet in C minor, the 40-year-old Brahms makes scarcely less dramatic a challenge than in the symphony in that key so soon to follow—that's to say in its two flanking movements. Here the Melos players are really in their element, projecting the music at the highest imaginable voltage in comparison with what I can only describe as the inner intensity of their rivals. In the Romanze it is the Italians who again give themselves just a bit more time to prise out inner secrets—with more sensitively accented detail in the dolce second subject. Honours are fairly equally divided in the A minor work, with the Melos perhaps the winners in extrovert rhythmic vitality (not least in the finale) and the Italians, again, in subtleties of phrasing. That is scarcely less true of the Third B flat Quartet, where the Melos make their points without unspecified yieldings of pulse or changes of tempo. In the final variations, for instance, their presentation of the theme may lack the charm of their rivals. But they don't take the liberty of transforming the wonderful molto dolce variation in G flat into a quasi slow movement.

The new recording is forward and vivid. Some people may prefer its vibrant brightness to the mellower, finger-grained Philips sound. For my own part I think it would still be the Italians who'd come with me to my desert island. But let me repeat: the German issue has virtues of its own that could win both composers many new friends.'

![Marius Neset - Time to Live (2026) [Hi-Res] Marius Neset - Time to Live (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771945711_folder.jpg)

![Eero Koivistoinen - For Children (1970) [2006] Eero Koivistoinen - For Children (1970) [2006]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771615516_ff.jpg)