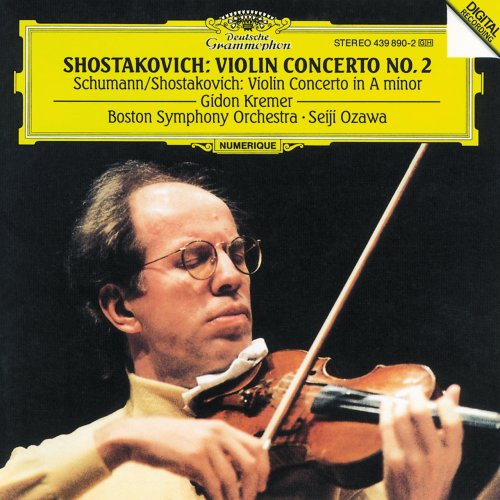

Gidon Kremer, Seiji Ozawa - Schumann, Shostakovich: Violin Concertos (1994)

Artist: Gidon Kremer, Seiji Ozawa

Title: Schumann, Shostakovich: Violin Concertos

Year Of Release: 1994

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 54:25

Total Size: 263 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Schumann, Shostakovich: Violin Concertos

Year Of Release: 1994

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 54:25

Total Size: 263 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906 - 1975)

Violin Concerto No.2 Op.129

1.1. Moderato 13:55

2. 2. Adagio 9:34

3. 3. Adagio - Allegro 8:20

Robert Schumann (1810 - 1856)

Cello Concerto in A Minor, Op. 129

Arr. for Violin by Schumann; Orch. Dmitri Shostakovich

. 1. Nicht zu schnell (Allegro non troppo) 10:44

5. 2. Langsam (Lento) 4:20

6. 3. Sehr lebhaft (Molto vivace) 7:26

Performers:

Gidon Kremer, violin

Boston Symphony Orchestra

Seiji Ozawa, conductor

Gidon Kremer, instead of coupling the Shostakovich Second Concerto with its natural partner, No. 1, enterprisingly chooses a concerto which Shostakovich labelled as his own Op. 129, but which in fact—confusingly enough—is Schumann's Op. 129. This is a novelty on two counts. Not only does it bring us Shostakovich's orchestration of the work, aiming to improve on Schumann's own, but for the first time to my knowledge puts on disc Schumann's violin version of his cello concerto. Shostakovich's aim in renovating the orchestration—with changes predominating in the tuttis—was to improve the work for his protege, Rostropovich.

In fact, as Kremer demonstrates, there is a lot to be said for the solution of using Shostakovich as an accompaniment for the violin version, inevitably lighter and brighter, when the main result of Shostakovich's tinkerings is to give more edge to the orchestral part, making the tuttis cleaner and bolder. Without knowing in advance, you would hardly register Shostakovich's use of two extra horns and piccolo, while even the addition of a harp is so discreet, you might not notice that either. The most noticeable difference comes in the tutti at the end of the exposition (fig. B, track 4, 3'34''), when bassoons take over the staccato triplet figures originally given to violas and second violins, but happily Richard Longman in his insert-notes is careful to specify other detailed differences.

Not surprisingly, the net result is a concerto, not just lighter than the cello version, but lacking the brilliance one usually asks for in a violin concerto, for Schumann's rewriting of the solo part is remarkably discreet, hardly exploiting the potential of the instrument. None the less, Kremer performs the piece with his usual flair and imagination, adopting speeds rather faster than those usual in the cello version, and the orchestra sounds fuller-bodied than in the genuine Shostakovich concerto, which comes as the coupling.

Like the Schumann, it was recorded live, but surprisingly—particularly when I remember Kremer's superb live Teldec recording of the Beethoven Concerto (12/93)—the tensions and concentration of the performance hardly reflect that. Compared with the studio recordings by Sitkovetsky and even more by the Gramophone Award-winning Mordkovitch, this is a relatively low-key performance. It is not so much the fault of Kremer as that of the orchestra, and more particularly the recording of the orchestra, lacking weight and body, and set rather backwardly. Even so, this is a positive and convincing reading of a work which increasingly defies criticism over its spareness, and clearly establishes itself as an inspired successor to the bolder Concerto No. 1. A good, provocative coupling.

In fact, as Kremer demonstrates, there is a lot to be said for the solution of using Shostakovich as an accompaniment for the violin version, inevitably lighter and brighter, when the main result of Shostakovich's tinkerings is to give more edge to the orchestral part, making the tuttis cleaner and bolder. Without knowing in advance, you would hardly register Shostakovich's use of two extra horns and piccolo, while even the addition of a harp is so discreet, you might not notice that either. The most noticeable difference comes in the tutti at the end of the exposition (fig. B, track 4, 3'34''), when bassoons take over the staccato triplet figures originally given to violas and second violins, but happily Richard Longman in his insert-notes is careful to specify other detailed differences.

Not surprisingly, the net result is a concerto, not just lighter than the cello version, but lacking the brilliance one usually asks for in a violin concerto, for Schumann's rewriting of the solo part is remarkably discreet, hardly exploiting the potential of the instrument. None the less, Kremer performs the piece with his usual flair and imagination, adopting speeds rather faster than those usual in the cello version, and the orchestra sounds fuller-bodied than in the genuine Shostakovich concerto, which comes as the coupling.

Like the Schumann, it was recorded live, but surprisingly—particularly when I remember Kremer's superb live Teldec recording of the Beethoven Concerto (12/93)—the tensions and concentration of the performance hardly reflect that. Compared with the studio recordings by Sitkovetsky and even more by the Gramophone Award-winning Mordkovitch, this is a relatively low-key performance. It is not so much the fault of Kremer as that of the orchestra, and more particularly the recording of the orchestra, lacking weight and body, and set rather backwardly. Even so, this is a positive and convincing reading of a work which increasingly defies criticism over its spareness, and clearly establishes itself as an inspired successor to the bolder Concerto No. 1. A good, provocative coupling.

DOWNLOAD FROM ISRA.CLOUD

Gidon Kreme Seiji Ozawa Schumann Shostakovich Violin Concertos 94 1411.rar - 263.9 MB

Gidon Kreme Seiji Ozawa Schumann Shostakovich Violin Concertos 94 1411.rar - 263.9 MB

![Maj Kavšek - MINOR FLAW (2026) [Hi-Res] Maj Kavšek - MINOR FLAW (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/09/8u50qjzftilnmaq7cws2iy3sg.jpg)

![Malene Mortensen & Christian Sands - Malene & Christian (2026) [Hi-Res] Malene Mortensen & Christian Sands - Malene & Christian (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770214038_ye95svxsd11r2_600.jpg)