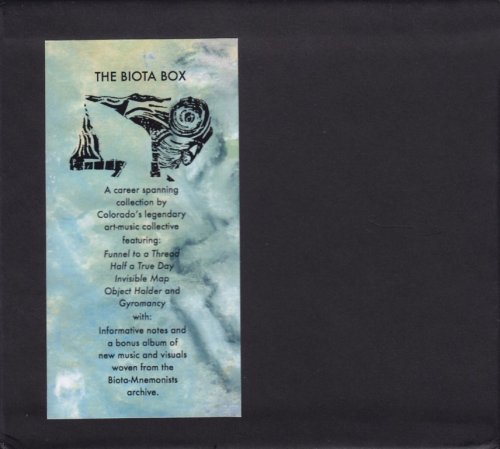

Biota / Mnemonists - The Biota Box (2019) {6CD Box Set}

- 04 Dec, 01:34

- change text size:

Facebook

Twitter

Artist: Biota / Mnemonists

Title: The Biota Box

Year Of Release: 2019

Label: ReR Megacorp #ReR Biota Box

Genre: Art Rock, Avant-Garde, Experimental

Quality: EAC Rip -> WavPack (Img+Cue,Log) / MP3 CBR320

Total Time: 05:48:55

Total Size: 1,9 Gb / 843 Mb (Full Scans ~ 1,2 Gb)

WebSite: Album Preview

Title: The Biota Box

Year Of Release: 2019

Label: ReR Megacorp #ReR Biota Box

Genre: Art Rock, Avant-Garde, Experimental

Quality: EAC Rip -> WavPack (Img+Cue,Log) / MP3 CBR320

Total Time: 05:48:55

Total Size: 1,9 Gb / 843 Mb (Full Scans ~ 1,2 Gb)

WebSite: Album Preview

Without any obvious keystone event, Biota – who started recording in the late 1970’s as the Mnemonist Orchestra – have quietly become a musical fixture, honoured for their uniquely, abstract, layered, polystylistic approach to musical construction - deaf to fashion or possible sales. And it seems, paradoxically, to have been just this art-orientated commercial indifference that has slowly won them loyal followers and surprisingly respectable sales. Now, for a wider audience - and at a congenial price - this box collects five representative releases that span their discography and track the radical evolution of their crystalline aesthetic – with added documentation, a band history, insights into their work process, and a full-length bonus CD embroidered from their archive of rare and unreleased material. Contents: Funnel to a Thread, Half a True Day, Invisible Map, Object Holder and Gyromancy (recorded as the Mnemonist Orchestra), and the box-only bonus Counterbalance.

Historical Notes, Biota, William Sharp

Reflecting on this period of Mnemonists and Biota development as we approach our 40th anniversary, I believe an important sensibility that has been retained by the group since inception is that of radio programming - the idea that marginally related material could be sequenced into a whole that best reflects life experiences.

1979.

The first record explored what a diverse group of instrumentalists from different backgrounds could produce spontaneously, live in the studio and without rehearsal. It was recorded at the studios of KCSU radio at Colorado State University, where a number of us were enrolled and doing on-air programming, sound engineering, visual arts and sciences.

"he four pieces were recorded live - unrehearsed and without retakes. The participants improvised within simple arrangements suggesting temporal and mood variables, as well as the arranger's underlying concepts. Taped environmental sounds were mixed in with live instruments [and spoken word] (ed.) as the improvisations developed. In many cases the element of chance figured significantly in the placement of these pre taped sounds relative to the other instruments."

(from the first press release for Mnemonist Orchestra LP, Dys 01)

1980.

By the second LP, we had taken this fluidity from radio into the studio formally and under more controlled circumstances and we began to experiment with the first digital processing devices we could get our hands on. The DeltaLab and Eventide companies obliged with their Acousticomputer and H949, respectively, though the tiniest digital delays were costly back then. We moved from converting the tile bathroom at the radio studio into a reverb chamber to the acquisition of a rich Great British Spring reverb. Key processing, however, remained mechanical in nature - I remember our engineer Mark Derbyshire wrapping a cylindrical Jim Rodgers loudspeaker in aluminum foil and miking it. Grand piano preparation included placement of small Neumann KM 84's directly on the strings. Similarly, guitarist Steve Scholbe would often set his amp on its back with the guitar resting flat over the speaker grill and play while controlling the feedback. Adults and children recited texts, and engineers wandered the streets with portable Nakamichi decks collecting sounds.

1981.

'Horde' was the first big reach for ambiguity. How far could we push the processing gear and still retain clarity and certainty of purpose? To what extent could we transform nature without an overwhelming sense that it was being done electronically? So, we made sure that most of our sources were acoustic. In this way, location recordings of IBM card-punch and teletype machines might mutate into an audio narrative of turmoil; or, mechanical equipment in the bowels of a building might swell into a larger urban setting via processing. Another challenge in the making of 'Horde' was how meaningfully to integrate medieval and renaissance instrumentation into this alien landscape. And, tape manipulation remained high on our agenda; I remember Mark and I running a loop that spanned a 15-foot room, tensioned by repurposed mike stands... It was at this time, too, that we played our first live concert - to accompany Mnemonist painter James Dixon's solo exhibit at the University. (Parts of the live recording found their way onto the first 'Biota' LP a year later.) In fact, CSU's art department proved a creatively rich resource: seven Mnemonists visual collaborators in addition to Dixon were linked to the program. As Biota evolved out of the larger, multi-media ensemble in later years, the visual component of the group retained the Mnemonists name.

1982.

Biota began as a subgroup of Mnemonists, building density not only from the digital processing of 'Horde' and 'Gyromancy', but also from the wild output of homemade devices created from the pages of 'Popular Electronics.' Steve Emmons and Rolf Goranson built and amassed gadgets from the old mags, with names like Audio Artist and Doomsday Alarm - all powered by 9-volt batteries and built up in layers using public school reel to reel machines we had salvaged from the landfill. Our first project was released on cassette as 'Roto-limbs' under the Mnemonists name which, in hindsight, was inaccurate. The content was something new, far more volatile - and far less refined - than, say, 'Gyromancy' and there was little commonality with the formal Mnemonists work. The 'Roto-limbs' philosophy was carried forward more elegantly in Mnemonists 'Biota' - essentially the first Biota LP. Again, it was rougher and more overtly electronic than earlier releases... and more appropriately Biota.

1983.

'Gyromancy' continued the Mnemonists' work and built on the 'Horde' philosophy. All sources were acoustic and were processed as radically (though often also as sparsely) as possible to achieve an environment that was elusive or perhaps not as it seemed... and not conventionally "electronic." Mark Derbyshire elaborates further on this in Part 2.

1984.

'Rackabones/Vagabones' introduced Biota's Bughouse Studio and our first use of multi-tracking. The group had settled into a working philosophy that explored our radio sensibility: that life was fluid and perturbed by occasional surprises - and that non-musical and musical sounds were continuously intermingled in our daily activities. So, we hit the streets again with mobile equipment; and the hillsides, rolling boulders down slopes and crashing through brush; we captured parks, restaurants, laboratories, concrete stairwells, HVAC rooms, the county fair - anywhere we could manipulate an interface between life's "noise” and musicality.

This was where the ambiguities of 'Horde' and 'Gyromancy' began to influence the Biota subgroup, though this aspect of our working philosophy wasn't to be fully refined for another 30 years.

Late '80s Bughouse.

This saw the move to 8 track and a sub-mix philosophy that carried us through 'Invisible Map'. It grew out of our conservation of tape generations in the earlier projects. We just naturally wanted to compartmentalize compositions into lumps of performance, and environmental vignettes. A main feature of this process was the drum-kit sub-mix. Not for the indecisive. Six tracks were filled with a solo kit (sometimes with single accompaniment, e.g. guitar) and this was processed and then submixed to the two open tracks. The six kit tracks would then slowly be lost as they were overrecorded by new ensemble parts. So, drum sub-mixes were fixed in the moment. The resulting sound became a central feature of our output from the late '80s - ‘90s because, once having been mixed in isolation, the drums tended to dominate final mix - since, when fixed, their accompaniment was not yet known. This translated into general accommodation for the fixed state of the kit as the arrangements around it were built.

Bughouse was a fine working environment, an early 20th c. home with a boxelder insect population and a basement loaded with old tins and tubs for percussive use; a few antique mic stands - and old floor lamps for illumination. We built an enclosure for the kit with mattresses, wood planks, and blankets. The mixing boards and outboard equipment rested on cinder blocks. 'Bellowing Room' and 'Tinct' were recorded under this spell, as was “Early Rest Home" for the 'ReR Quarterly'.

Late '80s Dys.

The subsequent move from Bughouse to the Mulberry studio in Fort Collins saw both refinement of our multi track sub-mix concept, and a gradual move away from the environmental recordings that were key to 'Vagabones' and 'Bellowing Room'. I think the intense interest in a spatial setting for the played parts remained; it was just implemented with increasingly refined digital spatial processors as they became available. The 'Ursa Major Stargate' being an example.

By 'Almost Never', environmental recordings from James Gardner, in Thailand, were themselves being processed into new spaces alien to those of the original. Again, the fluid sequencing of sub-compositions retained from radio was well represented in both this release and its predecessor, 'Tumble'. (Though we broke out of this to some extent for the more self contained compositions on the 'Awry' EP.)

Early '90s.

The full Mnemonists ensemble reformed under Mark and Amy Derbyshire's guidance for a year of composition and rehearsals aimed at live performance. The work was commissioned for the New Music America 1990 festival in Montreal. We set out to transport the full complement of 'Horde'/'Gyromancy' studio equipment to the stage for the event. Fragile outboard processing gear was divided amongst personnel and carried onboard our flights to Canada. In today’s world, I think we'd still be sitting in that special room trying to explain the purpose of those black boxes. The performance was accompanied by a large-screen video presentation above the stage, directed by Heidi Eversley. Live and rehearsal recordings from this event were eventually released as the 'Musique Actuelle 1990' CD.

'Almost Never' and 'Object Holder' involved further solidification of Biota's drum sub-mix methods, as we pressed on with 8 (and later 16) channels of multi-track during the '90s. The former album introduced formally notated wind sections by James Gardner. The latter brought in the singing of Susanne Lewis; percussion and words by Chris Cutler and a continuation of our collaboration with Charles O'Meara (aka Vrtacek) which had begun with 'Tumble' and 'Awry'.

It was during the making of 'Object Holder' that we first overtly witnessed the connections between unrelated performances and the way our studio processes could enable and encourage these сonnections. From the radio experience we were confident of these relationships, and our compositional style - sub-sections interlinked by segueways - allowed us to explore the connections and associated ambiguities. From this point on - and increasingly with each subsequent project - we saw entire ensembles form out of disparate material recorded in isolation and at different times. We began to arrange and "notate" compositions with blocks of performance, rather than the orchestration of notes on paper. For years, Chuck would send us piano recordings that integrated uncannily with our works in progress - works of which he had no knowledge. I remember him commenting on a passage in 'Map', and saying that he wanted to collaborate further with the cellist who wrote the accompaniment to his piano part. He was thrilled to learn that (a) it wasn't a cello, and (b) it was pulled serendipitously from another part of the project. So, there is much understanding and much unsaid among this scattered group of players. I can understand how Oswald, Musci, Venosta and others might see everything in the world as linked. They hear it everywhere. Back in our radio days, prior to forming the group, we would relish the challenge of long, impossible segueways. Decades of rewards were to follow.

"The Fowler" on 'Counterbalance' was built this way out of detached elements. The traditional song was recorded a cappella, with no immediate concept of how it might be arranged. Months later, the singing was joined by an autoharp from 'Funnel to a Thread's "Not a Single Thing" and a Hammond from that album's "More Than Say." These in turn were accompanied by interwoven orchestral fragments taken from two James Gardner compositions, themselves distinct and unrelated to the central song. Yet, all the components in the resulting arrangement are heard as harmonizing naturally without retuning.

Late 90's - present.

'Invisible Map' was our first project at the new mountainside studio. We felt the effects of the environment immediately: a sense of calm and reduced urgency. Genevieve Heistek joined us from Montreal and made the session work seem effortless. Her singing and violin were a perfect fit as we sought to expand the integration of song forms, for which Susanne lewis had provided the catalyst in her equally sympathetic work on 'Object Holder'.

We settled into the mountain environment fully with 'Haif a True Day'. A period of key additions to our range began with Kristianne Gale (singing and songwriting), David Zekman (bowed strings and mandolin), and Randy Miotke (Rhodes, brass, and engineering). This was also a turning point for me personally in becoming comfortable with a compositional language that would carry us forward to the present work. I saw it as a natural identity for the group. It took two decades to get here but, with 'Half a True Day', I felt an affinity for the working process that required no clamoring for technical solutions. It just became a natural way of doing things which, in turn, enabled refinements in other areas such as processing distillation, increased editing complexity and more elaborate arrangements. Both the latter were facilitated to a great degree by newly adopted software and our transition from 16-tracks of ADAT to a hard drive system. I slowly witnessed the mutation of my studio experience from being purely sonic (sound emanating from monitors) to a blend of sonic and visual (visualizations on a computer screen). Presently, I see the music almost as much as I hear it because the software interface has become so critical to the intensive editing process that allows us to assemble arrangements. Our days of razor blade and splicing block seem increasingly distant and remarkable. Looking back, the rewards these tools brought to studio composition were proportional to the hands-on physicality and perseverance involved. Today, their utility fades as liberating methods arise from the new technologies - no less labor intensive in their own way and arguably more powerful... and perhaps less purely musical.

Historical Notes, Mnemonists, Mark Derbyshire

Mnemonist Orchestra.

This was certainly a defining experience for us. While I knew in advance this would not be a typical KCSU live studio event, I arrived with my normal mindset that my role as the engineer was simply to render the performance as best as I could to tape or air. All such events involved some form of chaos, but this was far off the map - while there were a few predetermined ideas, much was to be spontaneously realized. When musicians come in cold to such a scenario, a lot happens by chance, and from an engineering point of view this makes capturing a live performance entirely ambiguous. Everyone in the studio and control room will hear something different, and there is no audience. What perspective does one attempt to capture?

The typical approach would be to drop each microphone/DI on a track and figure it out later. Of course we didn't have that luxury, which was a good thing, because a sterile mixdown session afterwards could never capture the same live "feel" as being there. My session concept quickly evolved to attempts to mix as much as I could with clarity, without letting it degenerate into mud. When a part was interfering too much, it would go down in the mix in relation to parts that were fitting better. This balance changed moment to moment, and maintaining a perspective on the parts buried in the mix was a challenge. How this proceeded was a matter not merely of my perspective, but of interaction between all those present.

Coming away from this was a disappointment to me. My whole reason for being a sound engineer was to record music with quality and accuracy beyond what most were achieving at the time. Much of the equipment used in the session was KCSU's - not of great quality and in marginal condition. Thus the recording was a decent document of the event, but a lot was lost.

'Attributes'.

For me this was a learning project. How should I combine the chance, chaos, and live-ness of our KCSU session with my classical music background and high-end audio bent? To create new soundsand colors for our palette, we were now experimenting with heavy signal processing. Our digital tools were brand new, allowing a near infinite range of adjustment and control. We explored these within practical limits, but a lot of potential was left on the table. Early digital processors introduced both desirable and undesirable artifacts; a lot of effort was invested into emphasizing the former while minimizing the latter. There was much processing of the processing.

One of the tenets I wanted to establish was that sounds we heard in the studio should be the same for the listener. We employed the finest recording equipment money could buy, often modified or built by us. This included most importantly a newly designed, still in construction mixing board, the digital effects processors, and Studer/Revox extra-wide half-track recorders running at higher speeds. Through experimentation I had determined this technology could maintain second-generation recording quality, nearly indistinguishable from first-generation. Thus my objective became that our final master tape should be at most one generation removed from the original recorded sounds. We didn't always follow this to the letter, but the vast majority of what appeared on the masters for each Mnemonists album, starting with 'Attributes' and continuing to the Montreal live performance, adhered to this dictum. At the time, a multitrack recording could never have achieved the sonic accuracy of our master.

This philosophy dictated that the master be a mixdown of live recording combined with playback of previous recordings of clean music and field sounds. That meant virtually all processing had to be done live during the final mix, although splices were acceptable between sections of the music. This was serendipitous in achieving much of the live feel from our first album.

For the field recordings I modified a high-end Nakamichi portable cassette deck with studio grade microphone preamps and phantom power for studio condenser microphones. While the quality was excellent, the limitations and roughness of cassette recordings did not meet my standards. For this reason, 'Attributes' was the last album where we used field recordings in exposed roles, without highly transformative processing.

My classical music background also drove me to plan more of what we wanted in the musical progression, with less dependence on chance. 'Attributes' did not achieve the clarity of our later efforts inasmuch as certain elements were unnecessary, inaudible, or detracted from the whole. However it was more spontaneous and a step along the way.

'Attributes' was our first attempt to cut a record in a high end audio environment. In production we had been cognizant of vinyl's sonic limitations, and the resulting master was expected to present only minor challenges to the cutting engineer. The cut was certainly excellent for the time, but still did not fully reflect the master tape.

'Horde'.

This was the largest Mnemonists leap In technique, technology, and approach. While some marginal source material made it onto the 'Attributes' master, none would appear in 'Horde'. Our concepts for digital processing had been greatly expanded, and we were dialing the Eventide and DeltaLab processors far beyond what they were designed to produce, to achieve the specific sounds we wanted. In some cases the units were "tricked" into working outside their comfort zone, but in other cases we hacked them and/or intertwined multiple devices internally. There was still plenty of straightforward processing, but it now took more of a back seat. Musically the previous albums had been largely improvised, but 'Horde' introduced written parts and arrangements, providing a more comfortable setting for the classically trained musicians without altering improvisational options for those working in that mode. We also incorporated a number of renaissance and medieval wind and string instruments to expand our tone color palette. We strove for a sound that started from acoustical sources, but could be highly processed. In most cases a recognizable acoustic element was retained. Overall, there was a lot more thought and planning put into how the arcs of each record side would proceed apart and together; rather than a collection of pieces or movements, the idea was to build a compositional and emotional path for the listener.

In terms of technology, 'Horde' represented a significant improvement in our ability to accurately render sounds we heard in the studio onto tape. Our tape machines had been further modified and our custom soundboard was becoming more flexible and functional. It was fully analog, without any digital processing or control. However it had been designed for highly complex live events and was generally more capable than contemporary commercial digitally controlled mixers. This gave us a further extension in the range of what we could accomplish in our live master mixdowns.

The process was exhausting and not terribly efficient. I felt we had lost something because of this, making the result a bit more sterile. The record cutting was much better than it had been for 'Attributes'. This was critical, because the master now pushed the limits of what could physically be cut onto vinyl. Still, the digital master recovered years later is closer to the original analog tape, if not quite accurate.

James Dixon Live Event.

This was our first attempt to produce a truly live performance. Many of our studio techniques were retained, but scaled back for practical reasons. The venue was small and acoustically poor, and some of the Mnemonists participants were either not familiar with our work, and/or were only there as a favor. We learned many lessons about the detail of preparation required for such a performance, and what could go wrong with something so complex. But while everything flowed, the result was closer to noise than we had intended. Whether the audience or musicians noticed, I can't say, but I was dissatisfied. Regardless, this performance made the Montreal live event possible, and successful, many years later.

'Gyromancy'.

This album became the culmination of everything we had done before. It was a major step beyond 'Horde', but not as much as 'Horde' was beyond 'Attributes'. 'Gyromancy' was a refinement, but significant enough that it wasn't obvious to me at the time whether the concept could betaken any further without declining into repetition. Many years later this is still ambiguous to me.

The processing gear for 'Gyromancy' was somewhat expanded compared to 'Horde', with factory modifications to existing units and extended digital delay time. The mixing board had long been completed and provided an all-analog soundpath from the microphone, essentially the same as listening to the original acoustic sound. The Studer soundpath electronics had been completely redesigned and coupled with a custom-designed transfer function unit conceptually related to the Dolby A and dbx noise reduction units of the time. Recorded analog sound at 30 ips had reached its zenith. We also enjoyed a bundle of high performance microphones that gave us more freedom to match the sounds of diverse instruments, and record many more instruments at the same time.

'Gyromancy' was conceived as a more precise, perhaps more controlled, version of 'Horde'. Virtually everything that happened on 'Gyromancy' was by design, even though chance still played a role. Compositionally it was more complex and subtle than 'Horde'. The 'Gyromancy' production schedule was streamlined to emphasize a cleaner, more live result than 'Horde', for which the production had been stretched to exhaustion, losing some of its spontaneity to overproduction. In this manner 'Gyromancy' was the result of fewer people working more. Everything was processed in some manner. This resulted in many sounds never before heard, often unrecognizable as coming from the instruments that produced them.

From the beginning, 'Gyromancy' was recorded with little regard to what could be transferred onto vinyl. We had rejected the idea of an early CD release because the A-to-D converters of that era could not have captured the range of the tone colors on the analog master tape. In this way, 'Gyromancy' was designed to be heard best in the future, and not at the time of its release. The only way to cut 'Gyromancy' on vinyl was at 45 rpm, under our supervision, and using our tape machine and studio equipment at the cutting studio. Bill and I drove overnight to California with the gear in the back, cut the record exactly as we intended, and ferried the results across Los Angeles for immediate plating before returning to Colorado. While this transfer was significantly better than anything else we had done, there was still some loss compared to the master. The later transfer to digital is the closest one can hear to the original master, but only in its 24-bit, 48K sampling incarnation. The CD sounds better than the vinyl original, but not quite as good as the full-data digital master.

'Nailed' and 'Tic'.

These were conceived as one-offs for a special Recommended UK project, and it was decided to base these on existing outtakes with fresh processing. Because of time constraints, the plan was to complete this project in an afternoon, and I think that is what happened. This limited the depth of the production and compositional elements, and yielded a much sparser sounding result than anything else we have done, before or after.

Montreal.

In terms of technology and technique refinement, this was the apogee of the Mnemonists work, although I consider 'Gyromancy' more successful overall. The intervening years had brought more capable digital sound processing devices with higher sound quality. At long last we could efficiently transform a sound concept in our heads into reality with our equipment. We still were stretching all of our equipment, new and old, well beyond design limits. The complexities required to produce a live show, exclusively from acoustic sounds and altered through sophisticated processing, were still within the grasp of our all-analog soundboard (unchanged since 'Gyromancy'), yet beyond what humans could reconfigure in real time. Thus we reluctantly added MIDI sequencers and storage devices, not to produce sound, but to switch rapidly between sound processing configurations. A number of our older processors were not MIDI capable and had to be reconfigured by hand, on the fly. Although the newer units could be reconfigured instantly, they were still tuned and adapted to the live music in real time by humans.

We began our preparation by cataloging a wide variety of experimental sound processings, many of which never saw the light of day. This was followed by sessions with the musicians to develop the overall arrangement and logistics of mixing everything live on stage. We further increased the variety of instruments employed, primarily in the realm of renaissance and medieval instruments. These included a number of instruments previously owned and played by the late David Munrow, a celebrated champion of early music.

Because of our limited numbers, no single person mixed the sound and oversaw the digital processing. In many cases several of us were involved simultaneously, even while we played instruments. Following the confusion and desperation of our previous attempt at live music, we adopted a more robust organizational strategy, leading to the creation of a 1-inch thick notebook detailing all the cue sheets required to replicate a performance. Still, no two performances were ever the same. Multiple final rehearsals in Colorado, and a dress rehearsal at the hall, refined the choreography required for both musical and engineering functions, and tweaked the overall sound and flow.

Our trip to Montreal was complicated by the fact that we transported the entire sound setup, excluding amplifiers and speakers, much of which was customized and not designed for the road. We carried most of the critical and irreplaceable gear onboard the airplanes. The soundboard required a custom case that was calculated to be on the edge of airline size and weight limits. Planning for and dealing with customs was also intricate, but nothing went wrong. What did go wrong was a snowstorm that, coupled with airline mistakes, left much of our equipment stuck in Toronto hours before the performance. Without it we would have to cancel, and at best it wasn't clear we would have enough time to set it up. Through luck or effort it arrived at the last minute. A rushed set up followed, leaving barely the time for a run-through of the music, prior to the performance.

The festival's sound engineer was clearly frustrated to find he would only receive a two-channel mix, and nothing more. I assume the video work came off as planned, though I never saw it. In the end, all our preparation paid off, and the music flowed well with only minor hitches. Early on we had realized that there was no way to record the rehearsals or show on analog tape, forcing the difficult decision to instead record to DAT. This guaranteed a decent recording, but it could never fully reproduce the quality of the stage mix. Forthe CD release, we chose a mixture of live and rehearsal material.

Reflecting on this period of Mnemonists and Biota development as we approach our 40th anniversary, I believe an important sensibility that has been retained by the group since inception is that of radio programming - the idea that marginally related material could be sequenced into a whole that best reflects life experiences.

1979.

The first record explored what a diverse group of instrumentalists from different backgrounds could produce spontaneously, live in the studio and without rehearsal. It was recorded at the studios of KCSU radio at Colorado State University, where a number of us were enrolled and doing on-air programming, sound engineering, visual arts and sciences.

"he four pieces were recorded live - unrehearsed and without retakes. The participants improvised within simple arrangements suggesting temporal and mood variables, as well as the arranger's underlying concepts. Taped environmental sounds were mixed in with live instruments [and spoken word] (ed.) as the improvisations developed. In many cases the element of chance figured significantly in the placement of these pre taped sounds relative to the other instruments."

(from the first press release for Mnemonist Orchestra LP, Dys 01)

1980.

By the second LP, we had taken this fluidity from radio into the studio formally and under more controlled circumstances and we began to experiment with the first digital processing devices we could get our hands on. The DeltaLab and Eventide companies obliged with their Acousticomputer and H949, respectively, though the tiniest digital delays were costly back then. We moved from converting the tile bathroom at the radio studio into a reverb chamber to the acquisition of a rich Great British Spring reverb. Key processing, however, remained mechanical in nature - I remember our engineer Mark Derbyshire wrapping a cylindrical Jim Rodgers loudspeaker in aluminum foil and miking it. Grand piano preparation included placement of small Neumann KM 84's directly on the strings. Similarly, guitarist Steve Scholbe would often set his amp on its back with the guitar resting flat over the speaker grill and play while controlling the feedback. Adults and children recited texts, and engineers wandered the streets with portable Nakamichi decks collecting sounds.

1981.

'Horde' was the first big reach for ambiguity. How far could we push the processing gear and still retain clarity and certainty of purpose? To what extent could we transform nature without an overwhelming sense that it was being done electronically? So, we made sure that most of our sources were acoustic. In this way, location recordings of IBM card-punch and teletype machines might mutate into an audio narrative of turmoil; or, mechanical equipment in the bowels of a building might swell into a larger urban setting via processing. Another challenge in the making of 'Horde' was how meaningfully to integrate medieval and renaissance instrumentation into this alien landscape. And, tape manipulation remained high on our agenda; I remember Mark and I running a loop that spanned a 15-foot room, tensioned by repurposed mike stands... It was at this time, too, that we played our first live concert - to accompany Mnemonist painter James Dixon's solo exhibit at the University. (Parts of the live recording found their way onto the first 'Biota' LP a year later.) In fact, CSU's art department proved a creatively rich resource: seven Mnemonists visual collaborators in addition to Dixon were linked to the program. As Biota evolved out of the larger, multi-media ensemble in later years, the visual component of the group retained the Mnemonists name.

1982.

Biota began as a subgroup of Mnemonists, building density not only from the digital processing of 'Horde' and 'Gyromancy', but also from the wild output of homemade devices created from the pages of 'Popular Electronics.' Steve Emmons and Rolf Goranson built and amassed gadgets from the old mags, with names like Audio Artist and Doomsday Alarm - all powered by 9-volt batteries and built up in layers using public school reel to reel machines we had salvaged from the landfill. Our first project was released on cassette as 'Roto-limbs' under the Mnemonists name which, in hindsight, was inaccurate. The content was something new, far more volatile - and far less refined - than, say, 'Gyromancy' and there was little commonality with the formal Mnemonists work. The 'Roto-limbs' philosophy was carried forward more elegantly in Mnemonists 'Biota' - essentially the first Biota LP. Again, it was rougher and more overtly electronic than earlier releases... and more appropriately Biota.

1983.

'Gyromancy' continued the Mnemonists' work and built on the 'Horde' philosophy. All sources were acoustic and were processed as radically (though often also as sparsely) as possible to achieve an environment that was elusive or perhaps not as it seemed... and not conventionally "electronic." Mark Derbyshire elaborates further on this in Part 2.

1984.

'Rackabones/Vagabones' introduced Biota's Bughouse Studio and our first use of multi-tracking. The group had settled into a working philosophy that explored our radio sensibility: that life was fluid and perturbed by occasional surprises - and that non-musical and musical sounds were continuously intermingled in our daily activities. So, we hit the streets again with mobile equipment; and the hillsides, rolling boulders down slopes and crashing through brush; we captured parks, restaurants, laboratories, concrete stairwells, HVAC rooms, the county fair - anywhere we could manipulate an interface between life's "noise” and musicality.

This was where the ambiguities of 'Horde' and 'Gyromancy' began to influence the Biota subgroup, though this aspect of our working philosophy wasn't to be fully refined for another 30 years.

Late '80s Bughouse.

This saw the move to 8 track and a sub-mix philosophy that carried us through 'Invisible Map'. It grew out of our conservation of tape generations in the earlier projects. We just naturally wanted to compartmentalize compositions into lumps of performance, and environmental vignettes. A main feature of this process was the drum-kit sub-mix. Not for the indecisive. Six tracks were filled with a solo kit (sometimes with single accompaniment, e.g. guitar) and this was processed and then submixed to the two open tracks. The six kit tracks would then slowly be lost as they were overrecorded by new ensemble parts. So, drum sub-mixes were fixed in the moment. The resulting sound became a central feature of our output from the late '80s - ‘90s because, once having been mixed in isolation, the drums tended to dominate final mix - since, when fixed, their accompaniment was not yet known. This translated into general accommodation for the fixed state of the kit as the arrangements around it were built.

Bughouse was a fine working environment, an early 20th c. home with a boxelder insect population and a basement loaded with old tins and tubs for percussive use; a few antique mic stands - and old floor lamps for illumination. We built an enclosure for the kit with mattresses, wood planks, and blankets. The mixing boards and outboard equipment rested on cinder blocks. 'Bellowing Room' and 'Tinct' were recorded under this spell, as was “Early Rest Home" for the 'ReR Quarterly'.

Late '80s Dys.

The subsequent move from Bughouse to the Mulberry studio in Fort Collins saw both refinement of our multi track sub-mix concept, and a gradual move away from the environmental recordings that were key to 'Vagabones' and 'Bellowing Room'. I think the intense interest in a spatial setting for the played parts remained; it was just implemented with increasingly refined digital spatial processors as they became available. The 'Ursa Major Stargate' being an example.

By 'Almost Never', environmental recordings from James Gardner, in Thailand, were themselves being processed into new spaces alien to those of the original. Again, the fluid sequencing of sub-compositions retained from radio was well represented in both this release and its predecessor, 'Tumble'. (Though we broke out of this to some extent for the more self contained compositions on the 'Awry' EP.)

Early '90s.

The full Mnemonists ensemble reformed under Mark and Amy Derbyshire's guidance for a year of composition and rehearsals aimed at live performance. The work was commissioned for the New Music America 1990 festival in Montreal. We set out to transport the full complement of 'Horde'/'Gyromancy' studio equipment to the stage for the event. Fragile outboard processing gear was divided amongst personnel and carried onboard our flights to Canada. In today’s world, I think we'd still be sitting in that special room trying to explain the purpose of those black boxes. The performance was accompanied by a large-screen video presentation above the stage, directed by Heidi Eversley. Live and rehearsal recordings from this event were eventually released as the 'Musique Actuelle 1990' CD.

'Almost Never' and 'Object Holder' involved further solidification of Biota's drum sub-mix methods, as we pressed on with 8 (and later 16) channels of multi-track during the '90s. The former album introduced formally notated wind sections by James Gardner. The latter brought in the singing of Susanne Lewis; percussion and words by Chris Cutler and a continuation of our collaboration with Charles O'Meara (aka Vrtacek) which had begun with 'Tumble' and 'Awry'.

It was during the making of 'Object Holder' that we first overtly witnessed the connections between unrelated performances and the way our studio processes could enable and encourage these сonnections. From the radio experience we were confident of these relationships, and our compositional style - sub-sections interlinked by segueways - allowed us to explore the connections and associated ambiguities. From this point on - and increasingly with each subsequent project - we saw entire ensembles form out of disparate material recorded in isolation and at different times. We began to arrange and "notate" compositions with blocks of performance, rather than the orchestration of notes on paper. For years, Chuck would send us piano recordings that integrated uncannily with our works in progress - works of which he had no knowledge. I remember him commenting on a passage in 'Map', and saying that he wanted to collaborate further with the cellist who wrote the accompaniment to his piano part. He was thrilled to learn that (a) it wasn't a cello, and (b) it was pulled serendipitously from another part of the project. So, there is much understanding and much unsaid among this scattered group of players. I can understand how Oswald, Musci, Venosta and others might see everything in the world as linked. They hear it everywhere. Back in our radio days, prior to forming the group, we would relish the challenge of long, impossible segueways. Decades of rewards were to follow.

"The Fowler" on 'Counterbalance' was built this way out of detached elements. The traditional song was recorded a cappella, with no immediate concept of how it might be arranged. Months later, the singing was joined by an autoharp from 'Funnel to a Thread's "Not a Single Thing" and a Hammond from that album's "More Than Say." These in turn were accompanied by interwoven orchestral fragments taken from two James Gardner compositions, themselves distinct and unrelated to the central song. Yet, all the components in the resulting arrangement are heard as harmonizing naturally without retuning.

Late 90's - present.

'Invisible Map' was our first project at the new mountainside studio. We felt the effects of the environment immediately: a sense of calm and reduced urgency. Genevieve Heistek joined us from Montreal and made the session work seem effortless. Her singing and violin were a perfect fit as we sought to expand the integration of song forms, for which Susanne lewis had provided the catalyst in her equally sympathetic work on 'Object Holder'.

We settled into the mountain environment fully with 'Haif a True Day'. A period of key additions to our range began with Kristianne Gale (singing and songwriting), David Zekman (bowed strings and mandolin), and Randy Miotke (Rhodes, brass, and engineering). This was also a turning point for me personally in becoming comfortable with a compositional language that would carry us forward to the present work. I saw it as a natural identity for the group. It took two decades to get here but, with 'Half a True Day', I felt an affinity for the working process that required no clamoring for technical solutions. It just became a natural way of doing things which, in turn, enabled refinements in other areas such as processing distillation, increased editing complexity and more elaborate arrangements. Both the latter were facilitated to a great degree by newly adopted software and our transition from 16-tracks of ADAT to a hard drive system. I slowly witnessed the mutation of my studio experience from being purely sonic (sound emanating from monitors) to a blend of sonic and visual (visualizations on a computer screen). Presently, I see the music almost as much as I hear it because the software interface has become so critical to the intensive editing process that allows us to assemble arrangements. Our days of razor blade and splicing block seem increasingly distant and remarkable. Looking back, the rewards these tools brought to studio composition were proportional to the hands-on physicality and perseverance involved. Today, their utility fades as liberating methods arise from the new technologies - no less labor intensive in their own way and arguably more powerful... and perhaps less purely musical.

Historical Notes, Mnemonists, Mark Derbyshire

Mnemonist Orchestra.

This was certainly a defining experience for us. While I knew in advance this would not be a typical KCSU live studio event, I arrived with my normal mindset that my role as the engineer was simply to render the performance as best as I could to tape or air. All such events involved some form of chaos, but this was far off the map - while there were a few predetermined ideas, much was to be spontaneously realized. When musicians come in cold to such a scenario, a lot happens by chance, and from an engineering point of view this makes capturing a live performance entirely ambiguous. Everyone in the studio and control room will hear something different, and there is no audience. What perspective does one attempt to capture?

The typical approach would be to drop each microphone/DI on a track and figure it out later. Of course we didn't have that luxury, which was a good thing, because a sterile mixdown session afterwards could never capture the same live "feel" as being there. My session concept quickly evolved to attempts to mix as much as I could with clarity, without letting it degenerate into mud. When a part was interfering too much, it would go down in the mix in relation to parts that were fitting better. This balance changed moment to moment, and maintaining a perspective on the parts buried in the mix was a challenge. How this proceeded was a matter not merely of my perspective, but of interaction between all those present.

Coming away from this was a disappointment to me. My whole reason for being a sound engineer was to record music with quality and accuracy beyond what most were achieving at the time. Much of the equipment used in the session was KCSU's - not of great quality and in marginal condition. Thus the recording was a decent document of the event, but a lot was lost.

'Attributes'.

For me this was a learning project. How should I combine the chance, chaos, and live-ness of our KCSU session with my classical music background and high-end audio bent? To create new soundsand colors for our palette, we were now experimenting with heavy signal processing. Our digital tools were brand new, allowing a near infinite range of adjustment and control. We explored these within practical limits, but a lot of potential was left on the table. Early digital processors introduced both desirable and undesirable artifacts; a lot of effort was invested into emphasizing the former while minimizing the latter. There was much processing of the processing.

One of the tenets I wanted to establish was that sounds we heard in the studio should be the same for the listener. We employed the finest recording equipment money could buy, often modified or built by us. This included most importantly a newly designed, still in construction mixing board, the digital effects processors, and Studer/Revox extra-wide half-track recorders running at higher speeds. Through experimentation I had determined this technology could maintain second-generation recording quality, nearly indistinguishable from first-generation. Thus my objective became that our final master tape should be at most one generation removed from the original recorded sounds. We didn't always follow this to the letter, but the vast majority of what appeared on the masters for each Mnemonists album, starting with 'Attributes' and continuing to the Montreal live performance, adhered to this dictum. At the time, a multitrack recording could never have achieved the sonic accuracy of our master.

This philosophy dictated that the master be a mixdown of live recording combined with playback of previous recordings of clean music and field sounds. That meant virtually all processing had to be done live during the final mix, although splices were acceptable between sections of the music. This was serendipitous in achieving much of the live feel from our first album.

For the field recordings I modified a high-end Nakamichi portable cassette deck with studio grade microphone preamps and phantom power for studio condenser microphones. While the quality was excellent, the limitations and roughness of cassette recordings did not meet my standards. For this reason, 'Attributes' was the last album where we used field recordings in exposed roles, without highly transformative processing.

My classical music background also drove me to plan more of what we wanted in the musical progression, with less dependence on chance. 'Attributes' did not achieve the clarity of our later efforts inasmuch as certain elements were unnecessary, inaudible, or detracted from the whole. However it was more spontaneous and a step along the way.

'Attributes' was our first attempt to cut a record in a high end audio environment. In production we had been cognizant of vinyl's sonic limitations, and the resulting master was expected to present only minor challenges to the cutting engineer. The cut was certainly excellent for the time, but still did not fully reflect the master tape.

'Horde'.

This was the largest Mnemonists leap In technique, technology, and approach. While some marginal source material made it onto the 'Attributes' master, none would appear in 'Horde'. Our concepts for digital processing had been greatly expanded, and we were dialing the Eventide and DeltaLab processors far beyond what they were designed to produce, to achieve the specific sounds we wanted. In some cases the units were "tricked" into working outside their comfort zone, but in other cases we hacked them and/or intertwined multiple devices internally. There was still plenty of straightforward processing, but it now took more of a back seat. Musically the previous albums had been largely improvised, but 'Horde' introduced written parts and arrangements, providing a more comfortable setting for the classically trained musicians without altering improvisational options for those working in that mode. We also incorporated a number of renaissance and medieval wind and string instruments to expand our tone color palette. We strove for a sound that started from acoustical sources, but could be highly processed. In most cases a recognizable acoustic element was retained. Overall, there was a lot more thought and planning put into how the arcs of each record side would proceed apart and together; rather than a collection of pieces or movements, the idea was to build a compositional and emotional path for the listener.

In terms of technology, 'Horde' represented a significant improvement in our ability to accurately render sounds we heard in the studio onto tape. Our tape machines had been further modified and our custom soundboard was becoming more flexible and functional. It was fully analog, without any digital processing or control. However it had been designed for highly complex live events and was generally more capable than contemporary commercial digitally controlled mixers. This gave us a further extension in the range of what we could accomplish in our live master mixdowns.

The process was exhausting and not terribly efficient. I felt we had lost something because of this, making the result a bit more sterile. The record cutting was much better than it had been for 'Attributes'. This was critical, because the master now pushed the limits of what could physically be cut onto vinyl. Still, the digital master recovered years later is closer to the original analog tape, if not quite accurate.

James Dixon Live Event.

This was our first attempt to produce a truly live performance. Many of our studio techniques were retained, but scaled back for practical reasons. The venue was small and acoustically poor, and some of the Mnemonists participants were either not familiar with our work, and/or were only there as a favor. We learned many lessons about the detail of preparation required for such a performance, and what could go wrong with something so complex. But while everything flowed, the result was closer to noise than we had intended. Whether the audience or musicians noticed, I can't say, but I was dissatisfied. Regardless, this performance made the Montreal live event possible, and successful, many years later.

'Gyromancy'.

This album became the culmination of everything we had done before. It was a major step beyond 'Horde', but not as much as 'Horde' was beyond 'Attributes'. 'Gyromancy' was a refinement, but significant enough that it wasn't obvious to me at the time whether the concept could betaken any further without declining into repetition. Many years later this is still ambiguous to me.

The processing gear for 'Gyromancy' was somewhat expanded compared to 'Horde', with factory modifications to existing units and extended digital delay time. The mixing board had long been completed and provided an all-analog soundpath from the microphone, essentially the same as listening to the original acoustic sound. The Studer soundpath electronics had been completely redesigned and coupled with a custom-designed transfer function unit conceptually related to the Dolby A and dbx noise reduction units of the time. Recorded analog sound at 30 ips had reached its zenith. We also enjoyed a bundle of high performance microphones that gave us more freedom to match the sounds of diverse instruments, and record many more instruments at the same time.

'Gyromancy' was conceived as a more precise, perhaps more controlled, version of 'Horde'. Virtually everything that happened on 'Gyromancy' was by design, even though chance still played a role. Compositionally it was more complex and subtle than 'Horde'. The 'Gyromancy' production schedule was streamlined to emphasize a cleaner, more live result than 'Horde', for which the production had been stretched to exhaustion, losing some of its spontaneity to overproduction. In this manner 'Gyromancy' was the result of fewer people working more. Everything was processed in some manner. This resulted in many sounds never before heard, often unrecognizable as coming from the instruments that produced them.

From the beginning, 'Gyromancy' was recorded with little regard to what could be transferred onto vinyl. We had rejected the idea of an early CD release because the A-to-D converters of that era could not have captured the range of the tone colors on the analog master tape. In this way, 'Gyromancy' was designed to be heard best in the future, and not at the time of its release. The only way to cut 'Gyromancy' on vinyl was at 45 rpm, under our supervision, and using our tape machine and studio equipment at the cutting studio. Bill and I drove overnight to California with the gear in the back, cut the record exactly as we intended, and ferried the results across Los Angeles for immediate plating before returning to Colorado. While this transfer was significantly better than anything else we had done, there was still some loss compared to the master. The later transfer to digital is the closest one can hear to the original master, but only in its 24-bit, 48K sampling incarnation. The CD sounds better than the vinyl original, but not quite as good as the full-data digital master.

'Nailed' and 'Tic'.

These were conceived as one-offs for a special Recommended UK project, and it was decided to base these on existing outtakes with fresh processing. Because of time constraints, the plan was to complete this project in an afternoon, and I think that is what happened. This limited the depth of the production and compositional elements, and yielded a much sparser sounding result than anything else we have done, before or after.

Montreal.

In terms of technology and technique refinement, this was the apogee of the Mnemonists work, although I consider 'Gyromancy' more successful overall. The intervening years had brought more capable digital sound processing devices with higher sound quality. At long last we could efficiently transform a sound concept in our heads into reality with our equipment. We still were stretching all of our equipment, new and old, well beyond design limits. The complexities required to produce a live show, exclusively from acoustic sounds and altered through sophisticated processing, were still within the grasp of our all-analog soundboard (unchanged since 'Gyromancy'), yet beyond what humans could reconfigure in real time. Thus we reluctantly added MIDI sequencers and storage devices, not to produce sound, but to switch rapidly between sound processing configurations. A number of our older processors were not MIDI capable and had to be reconfigured by hand, on the fly. Although the newer units could be reconfigured instantly, they were still tuned and adapted to the live music in real time by humans.

We began our preparation by cataloging a wide variety of experimental sound processings, many of which never saw the light of day. This was followed by sessions with the musicians to develop the overall arrangement and logistics of mixing everything live on stage. We further increased the variety of instruments employed, primarily in the realm of renaissance and medieval instruments. These included a number of instruments previously owned and played by the late David Munrow, a celebrated champion of early music.

Because of our limited numbers, no single person mixed the sound and oversaw the digital processing. In many cases several of us were involved simultaneously, even while we played instruments. Following the confusion and desperation of our previous attempt at live music, we adopted a more robust organizational strategy, leading to the creation of a 1-inch thick notebook detailing all the cue sheets required to replicate a performance. Still, no two performances were ever the same. Multiple final rehearsals in Colorado, and a dress rehearsal at the hall, refined the choreography required for both musical and engineering functions, and tweaked the overall sound and flow.

Our trip to Montreal was complicated by the fact that we transported the entire sound setup, excluding amplifiers and speakers, much of which was customized and not designed for the road. We carried most of the critical and irreplaceable gear onboard the airplanes. The soundboard required a custom case that was calculated to be on the edge of airline size and weight limits. Planning for and dealing with customs was also intricate, but nothing went wrong. What did go wrong was a snowstorm that, coupled with airline mistakes, left much of our equipment stuck in Toronto hours before the performance. Without it we would have to cancel, and at best it wasn't clear we would have enough time to set it up. Through luck or effort it arrived at the last minute. A rushed set up followed, leaving barely the time for a run-through of the music, prior to the performance.

The festival's sound engineer was clearly frustrated to find he would only receive a two-channel mix, and nothing more. I assume the video work came off as planned, though I never saw it. In the end, all our preparation paid off, and the music flowed well with only minor hitches. Early on we had realized that there was no way to record the rehearsals or show on analog tape, forcing the difficult decision to instead record to DAT. This guaranteed a decent recording, but it could never fully reproduce the quality of the stage mix. Forthe CD release, we chose a mixture of live and rehearsal material.

| |

***************

Track List CD1: Biota – Object Holder (1995)

01. Bumpreader [7:52]

02. Spillway [4:15]

03. Eavesdrop [1:46]

04. Blind Corner [2:22]

05. Under the Hat [1:33]

06. Flatwheel [2:08]

07. Reckoning Falls [2:40]

08. Swallow [0:39]

09. Move [1:15]

10. Steam Trader [2:49]

11. Understander [2:43]

12. Private Wire [3:03]

13. Cinder [1:26]

14. Distraction [5:41]

15. Signal [3:33]

16. This Ridge [0:44]

17. Idea for a Wagon [3:21]

18. More Silence [4:03]

19. Coat [1:58]

20. Gate Climbing [5:31]

21. Protector [3:03]

22. Visible Gap [1:39]

23. The Trunk [4:03]

24. Unknown Title [2:09]

Track List CD2: Biota – Invisible Map (2001)

01. Moment [0:44]

02. The Rapid Color [3:46]

03. Port [2:59]

04. Call [2:37]

05. Landless [2:39]

06. Air on Water [0:29]

07. Mineral [3:20]

08. Common Broom [2:12]

09. Birthday [3:30]

10. Dustman [0:52]

11. Sleeping Car [2:25]

12. Snake Out [3:21]

13. Occurrence [1:36]

14. Top Ray Done [1:59]

15. Glass Lizard [2:09]

16. Telegraph Plant [0:56]

17. Spoonbender's Visit [0:55]

18. Remodel a Whisper [0:33]

19. Measured Not Found [3:22]

20. The Slow Forest [4:30]

21. Canopy [0:46]

22. Red's Big Day [1:32]

23. Lampblack [1:34]

24. There Is Probably Something [0:38]

25. Worry Hill [1:28]

26. Olive Drab Marionette [1:15]

27. Invisible Gap [1:19]

28. Yarn [3:18]

29. Words Disappear [1:23]

30. Ballad Of [2:06]

31. Soil & Token [1:38]

32. Glazed Paper [3:21]

33. Paste [3:09]

34. Truth Table [0:57]

35. Dual [3:24]

36. Flicker [2:39]

37. Presto the Human [1:03]

Track List CD3: Mnemonists – Gyromancy (2004)

01. Gyromancy A [19:48]

02. Gyromancy B [19:03]

03. Nailed [4:21]

04. Tic [4:15]

Track List CD4: Biota – Half A True Day (2007)

01. Figure Question [1:46]

02. Pack-and-Penny Day [1:36]

03. Hidden Compartment [1:33]

04. Angle of Doubt [2:55]

05. Proven Within Half; Half a True Day [8:19]

06. Accidental Photograph [2:44]

07. Winding Nth [10:30]

08. Moth Across [2:56]

09. Silent Grove [2:42]

10. Just Now Maybe [2:22]

11. Another Name [3:53]

12. Turn the Moon [3:11]

13. Globemallow, Left Untold [3:03]

14. Cloud Chamber [2:38]

15. Where No One Knows [2:29]

16. Antimagnet [2:26]

17. Passerine [14:37]

Track List CD5: Biota – Funnel To A Thread (2014)

01. Falling in Wood [3:07]

02. Receptor [1:29]

03. Double Unfound [1:27]

04. Hearsay [4:03]

05. Half Dwelling [3:04]

06. Shed [1:34]

07. Misnoticed [3:29]

08. Understory [2:34]

09. Numberless Years [3:28]

10. A Dozen Moons [3:15]

11. Winder [2:42]

12. Not a Single Thing [4:03]

13. More Than Say [1:34]

14. Take Warning [4:15]

15. The Land Away [3:39]

16. Whirl Round [1:33]

17. Hand Nor Glove [1:40]

18. High Painted Streets [1:13]

19. Till Time and Times [5:01]

20. Usually the Guesser [2:20]

21. Choosehow [1:35]

Track List CD6: Biota - Counterbalance (2019)

01. Lamp [0:44]

02. Fishing Song [1:13]

03. Droplets [4:46]

04. By Turning [4:22]

05. The Fowler [3:49]

06. Only After [2:13]

07. Alight [0:52]

08. Buy Me a Secret [2:20]

09. Welcome to See [2:15]

10. Asterisk [5:22]

![Nils Wülker - Zuversicht (2026) [Hi-Res] Nils Wülker - Zuversicht (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769611944_ahp1eqi4eu7na_600.jpg)

![Dewa Budjana, Czech Symphony Orchestra - PragueNayama (2026) [Hi-Res] Dewa Budjana, Czech Symphony Orchestra - PragueNayama (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/30/svtc5ews9mwy8fxfbhiwifo2f.jpg)

![Cimota - [ˈkɪmɔtɑː] (2026) [Hi-Res] Cimota - [ˈkɪmɔtɑː] (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769770149_b9yit5jywtto9_600.jpg)