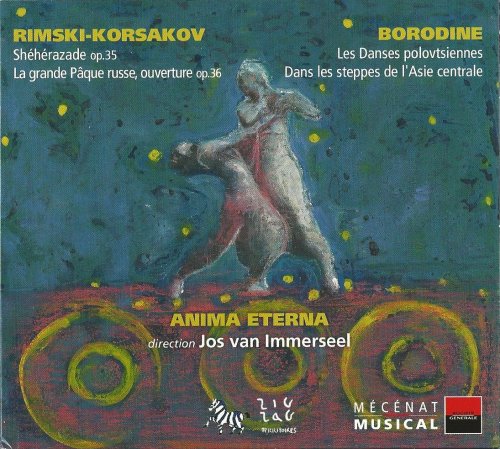

Anima Eterna, Jos van Immerseel - Rimsky-Korsakov: Sheherazade, Borodine (2005)

Artist: Anima Eterna, Jos van Immerseel

Title: Rimsky-Korsakov: Sheherazade, Borodine

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: Zig Zag Territoires

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:16:12

Total Size: 367 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Rimsky-Korsakov: Sheherazade, Borodine

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: Zig Zag Territoires

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:16:12

Total Size: 367 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Scheherazade, symphonic suite for orchestra, Op. 35: La mer et le bateau de Simbad [0:09:33.67]

02. Scheherazade, symphonic suite for orchestra, Op. 35: Le récit du prince Kalender [0:11:55.25]

03. Scheherazade, symphonic suite for orchestra, Op. 35: Le jeune Prince et la Princesse [0:09:50.01]

04. Scheherazade, symphonic suite for orchestra, Op. 35: La fête à Bagdad - la mer - le naufrage du bateau sur les rochers [0:11:55.55]

05. Russian Easter Festival Overture (Svetlïy pazdnik), for orchestra, Op. 36 [0:14:59.39]

06. In the Steppes of Central Asia (V sredney Azii), musical picture for orchestra [0:06:49.30]

07. Prince Igor, opera (completed by Rimsky-Korsakov & Glazunov): Introduction: Danse des jeunes filles [0:00:43.49]

08. Prince Igor, opera (completed by Rimsky-Korsakov & Glazunov): Danse des hommes [0:01:25.53]

09. Prince Igor, opera (completed by Rimsky-Korsakov & Glazunov): Danse collective [0:01:19.69]

10. Prince Igor, opera (completed by Rimsky-Korsakov & Glazunov): Danse des garçons [0:02:04.58]

11. Prince Igor, opera (completed by Rimsky-Korsakov & Glazunov): Danse finale [0:05:40.44]

Performers:

Anima Eterna [on period instruments]

Jos van Immerseel - conductor

I wouldn’t have thought the world was anxiously waiting for a historically informed performance of Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade . Written in 1888 and a masterpiece of orchestration, it would seem that this was one work that really cries out for the full resources of a modern symphony orchestra. So I was surprised when I saw a listing for this new recording with the Bruges-based period-instrument ensemble, Anima Eterna. Despite all the heat generated in some quarters, I remain fairly neutral regarding H.I.P., seeing it neither as the salvation of music from 20th-century excesses nor as the death of music through formalism. At their best, H.I.P. performances throw a different light on the overly familiar. I—and I know many others—hear Beethoven, Bruckner, even Strauss, Elgar and Tchaikovsky a bit differently through the good offices of Zinman, Herreweghe, Harnoncourt, Norrington, and others. But, Scheherazade ? I decided to throw aside preconceptions. I am glad I did, for the experience was truly ear opening.

I thought I knew the works on this disc. These pieces, after all, almost define the term “war-horse.” I was unprepared for the incredible richness these performances offer. Here were colors and harmonies that I simply did not remember hearing in these works before. The experience sent me back to my stacks for a refresher. I listened to a variety of recordings, dating from the 1927 Stokowski to the 2002 Gergiev. What I heard validated Jos van Immerseel’s statement that “frequently performed pieces are often subject to wear.” There were fine performances ranging from the sensuous (Stokowski, Serebrier) to the dramatic (Reiner, Kondrashin) to the charming (Beecham, Mata?i?). All of these, however, emphasized the strings to the detriment of the woodwinds, and sometimes even the brass, in a way I had not noticed before. Where I had expected the modern orchestras to provide the greater resources of color, the opposite turned out to be the case. Only three recordings—the Dorati/Minneapolis Symphony on Mercury 462953 (available on an arkivmusic.com CD reissue), the Mata?i?/Philharmonia on EMI (currently on Testament 1329), and the Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic on Deutsche Grammophon (Originals 463614)—came close to offering the wind detail and exquisite balance between sections and choirs offered by the Anima Eterna orchestra. None of these would be among my first choices, though I like the first two very much. The Dorati, admittedly with a smaller than typical string section, achieves its magic through a very dry acoustic; the Mata?i?, through careful balancing and lower dynamic levels during much of the work; the Karajan, through super-human wind-playing and (I suspect) some brute-force technical manipulation.

None of this is needed by Immerseel and his band. The comparatively small string section (8-8-6-6-5) balances well with the wind choirs at every dynamic level. Minimal vibrato, while it sounds a bit stark to 21st-century ears, creates great transparency. The smaller-bore low brass have great presence, even when playing softly, and snarl marvelously when played forte. French horns are clearly audible without having to blast over a huge string section. As a bassoonist, I was particularly pleased to hear the second bassoon parts balanced with the double basses and trombones. Intonation throughout is exceptional and precision is often amazing.

None of this would matter, of course, if the performances were second-rate. This performance of Scheherazade deserves to be considered in the same company as any of my previous favorites: early Stokowski (Biddulph 10-OP, Cala 521), Beecham (EMI 66998), Reiner (RCA 66377 SACD), Kondrashin (Philips Originals 000708802), Haitink (Philips 420898, out of print, but worth looking for), and Serebrier (Reference 89). Unlike Gergiev in the recent Kirov recording on Philips 470840, the dynamics are observed and climaxes are effectively built. Unlike the generally fine Spano on Telarc 80568, tension does not wane. Though intrinsically smaller scaled than competing recordings, which use orchestras much larger than the 59 players employed here, there is no lack of power at the climaxes. In fact, the lower brass and percussion here are more impressive than on most recordings. And the thrill of hearing all that newly revealed color and detail at all dynamic levels cannot be gainsaid. As compensation for the scale, there is a sense of intimacy in this performance that I have found only in the Beecham and Mata?i?. This is especially evident in the wonderfully poised third movement, which is characterized by some of the most beautiful string tone I have ever heard. Among the highlights of the performance are the violin solos, performed by concertmaster Midori Seiler. She uses vibrato sparingly and expressively. If she is not quite the equal of Krebbers, Friend, or Hilsberg in terms of interpretive imagination, she does not at all embarrass herself in this company.

The performance of the Russian Easter Festival Overture , based on Russian liturgical chants and composed in the same year as Scheherazade , is equally fine and just as much of a surprise. The use of smaller-bore trombones is especially telling in this piece, where they have so prominent a part. Modern instruments can sound bland at lower dynamics, but that is certainly not a problem here. The trombone solos are especially well taken by tenor trombonist Cas Gevers. However, it is the woodwinds, again, that really distinguish this recording. The distinctive coloration of period instruments give an exotic quality to the wind choruses that suggests the sound of Orthodox liturgical chant in a way I’d never noticed before, despite the origins of this work.

A couple of quibbles must be noted here: there was a bit of uncharacteristic scrappiness in the playing of the violins in this work and the trumpets really were not sufficiently powerful to cap a couple of chords effectively. These are very small issues, but deserve mention, given the prevailing high standards.

The Borodin selections sound less startling, though they, too, are very well performed. The high unison violin part at the beginning of In the Steppes of Central Asia , composed for the 25th anniversary of Czar Alexander II’s ascension to the Russian throne, is usually played with little or no vibrato, so this will sound familiar. The proudly marcato approach taken elsewhere by Immerseel is just right for this attractive piece of imperial propaganda. The “Polovtsian Dances,” from the opera Prince Igor , are very familiar to most listeners. Because they depend heavily on wind-writing, with little sustained string-writing, the contrast with modern-instrument performances is less than in the other works on this disc. Bass trombonists and percussionists will love the fourth dance.

There are informative notes regarding all of the works in French, English, and German, as well as comments on performance practice by the conductor. The sound quality is excellent and the presentation attractive. For those allergic to H.I.P. who don’t have a recording of Scheherazade (hard as that is to imagine), any of the favorites listed above should serve. One can almost choose on the basis of need for modern sound and find a happy match. For anyone else who wants to hear this familiar repertoire in an exciting new way, I cannot recommend this release highly enough. -- Ronald E. Grames

I thought I knew the works on this disc. These pieces, after all, almost define the term “war-horse.” I was unprepared for the incredible richness these performances offer. Here were colors and harmonies that I simply did not remember hearing in these works before. The experience sent me back to my stacks for a refresher. I listened to a variety of recordings, dating from the 1927 Stokowski to the 2002 Gergiev. What I heard validated Jos van Immerseel’s statement that “frequently performed pieces are often subject to wear.” There were fine performances ranging from the sensuous (Stokowski, Serebrier) to the dramatic (Reiner, Kondrashin) to the charming (Beecham, Mata?i?). All of these, however, emphasized the strings to the detriment of the woodwinds, and sometimes even the brass, in a way I had not noticed before. Where I had expected the modern orchestras to provide the greater resources of color, the opposite turned out to be the case. Only three recordings—the Dorati/Minneapolis Symphony on Mercury 462953 (available on an arkivmusic.com CD reissue), the Mata?i?/Philharmonia on EMI (currently on Testament 1329), and the Karajan/Berlin Philharmonic on Deutsche Grammophon (Originals 463614)—came close to offering the wind detail and exquisite balance between sections and choirs offered by the Anima Eterna orchestra. None of these would be among my first choices, though I like the first two very much. The Dorati, admittedly with a smaller than typical string section, achieves its magic through a very dry acoustic; the Mata?i?, through careful balancing and lower dynamic levels during much of the work; the Karajan, through super-human wind-playing and (I suspect) some brute-force technical manipulation.

None of this is needed by Immerseel and his band. The comparatively small string section (8-8-6-6-5) balances well with the wind choirs at every dynamic level. Minimal vibrato, while it sounds a bit stark to 21st-century ears, creates great transparency. The smaller-bore low brass have great presence, even when playing softly, and snarl marvelously when played forte. French horns are clearly audible without having to blast over a huge string section. As a bassoonist, I was particularly pleased to hear the second bassoon parts balanced with the double basses and trombones. Intonation throughout is exceptional and precision is often amazing.

None of this would matter, of course, if the performances were second-rate. This performance of Scheherazade deserves to be considered in the same company as any of my previous favorites: early Stokowski (Biddulph 10-OP, Cala 521), Beecham (EMI 66998), Reiner (RCA 66377 SACD), Kondrashin (Philips Originals 000708802), Haitink (Philips 420898, out of print, but worth looking for), and Serebrier (Reference 89). Unlike Gergiev in the recent Kirov recording on Philips 470840, the dynamics are observed and climaxes are effectively built. Unlike the generally fine Spano on Telarc 80568, tension does not wane. Though intrinsically smaller scaled than competing recordings, which use orchestras much larger than the 59 players employed here, there is no lack of power at the climaxes. In fact, the lower brass and percussion here are more impressive than on most recordings. And the thrill of hearing all that newly revealed color and detail at all dynamic levels cannot be gainsaid. As compensation for the scale, there is a sense of intimacy in this performance that I have found only in the Beecham and Mata?i?. This is especially evident in the wonderfully poised third movement, which is characterized by some of the most beautiful string tone I have ever heard. Among the highlights of the performance are the violin solos, performed by concertmaster Midori Seiler. She uses vibrato sparingly and expressively. If she is not quite the equal of Krebbers, Friend, or Hilsberg in terms of interpretive imagination, she does not at all embarrass herself in this company.

The performance of the Russian Easter Festival Overture , based on Russian liturgical chants and composed in the same year as Scheherazade , is equally fine and just as much of a surprise. The use of smaller-bore trombones is especially telling in this piece, where they have so prominent a part. Modern instruments can sound bland at lower dynamics, but that is certainly not a problem here. The trombone solos are especially well taken by tenor trombonist Cas Gevers. However, it is the woodwinds, again, that really distinguish this recording. The distinctive coloration of period instruments give an exotic quality to the wind choruses that suggests the sound of Orthodox liturgical chant in a way I’d never noticed before, despite the origins of this work.

A couple of quibbles must be noted here: there was a bit of uncharacteristic scrappiness in the playing of the violins in this work and the trumpets really were not sufficiently powerful to cap a couple of chords effectively. These are very small issues, but deserve mention, given the prevailing high standards.

The Borodin selections sound less startling, though they, too, are very well performed. The high unison violin part at the beginning of In the Steppes of Central Asia , composed for the 25th anniversary of Czar Alexander II’s ascension to the Russian throne, is usually played with little or no vibrato, so this will sound familiar. The proudly marcato approach taken elsewhere by Immerseel is just right for this attractive piece of imperial propaganda. The “Polovtsian Dances,” from the opera Prince Igor , are very familiar to most listeners. Because they depend heavily on wind-writing, with little sustained string-writing, the contrast with modern-instrument performances is less than in the other works on this disc. Bass trombonists and percussionists will love the fourth dance.

There are informative notes regarding all of the works in French, English, and German, as well as comments on performance practice by the conductor. The sound quality is excellent and the presentation attractive. For those allergic to H.I.P. who don’t have a recording of Scheherazade (hard as that is to imagine), any of the favorites listed above should serve. One can almost choose on the basis of need for modern sound and find a happy match. For anyone else who wants to hear this familiar repertoire in an exciting new way, I cannot recommend this release highly enough. -- Ronald E. Grames

DOWNLOAD FROM ISRA.CLOUD

Anima Eterna Jos van Immerseel Rimsky-Korsakov Sheherazade Borodine 05 1501.rar - 367.3 MB

Anima Eterna Jos van Immerseel Rimsky-Korsakov Sheherazade Borodine 05 1501.rar - 367.3 MB

![Metropole Orkest - Arakatak (2026) [Hi-Res] Metropole Orkest - Arakatak (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772636683_1.jpg)

![Hugh Masekela - The Emancipation Of Hugh Masekela (2026) [Hi-Res] Hugh Masekela - The Emancipation Of Hugh Masekela (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772762847_xwb94ryupobdj_600.jpg)

![Brian Jackson & Masters At Work - EP Two (2026) [Hi-Res] Brian Jackson & Masters At Work - EP Two (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772621441_lhj1cghnuc4bc_600.jpg)

![Peter Rom Trio - Wanting Machine II (2026) [Hi-Res] Peter Rom Trio - Wanting Machine II (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/06/xqb61fir0vlk01ep5rpwh5r1h.jpg)

![Thomas Bergsten Trio - Chill Microtonal Free Jazz and Modern Composition To Study To (2026) [Hi-Res] Thomas Bergsten Trio - Chill Microtonal Free Jazz and Modern Composition To Study To (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772434983_p1cagvb6yegof_600.jpg)

![Ike - Clay EP (2026) [Hi-Res] Ike - Clay EP (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/06/b5v5wuysnriwvsgx2wy37w5t9.jpg)