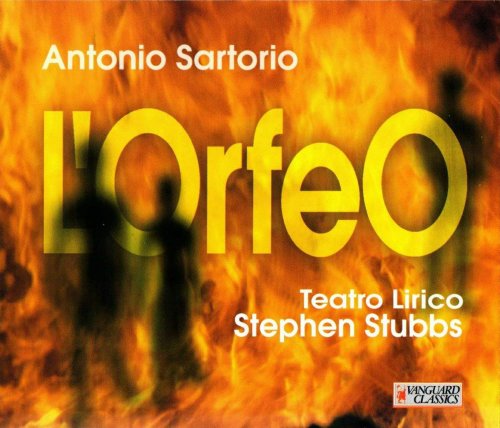

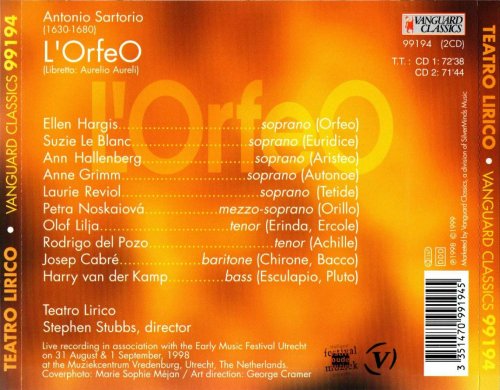

Stephen Stubbs, Teatro Lirico - Sartorio: L'Orfeo (1999)

Artist: Stephen Stubbs, Teatro Lirico

Title: Sartorio: L'Orfeo

Year Of Release: 1999

Label: Vanguard Classics

Genre: Clasical opera

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 02:24:30

Total Size: 652 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Sartorio: L'Orfeo

Year Of Release: 1999

Label: Vanguard Classics

Genre: Clasical opera

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 02:24:30

Total Size: 652 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

CD1

01. Sinfonia

ATTO 1

02. Cara e amabile catena (Euridice, Orfeo, Esculapio)

03. Aita, soccorso, correte, signore (Erinda, Orfeo, Euridice)

04. Arde per Euridice (Erinda)

05. Ruscelletti, che sciogliete (Autonoe)

06. O care selve. O libertà gradita (Orillo, Autonoe)

07. S'atterri, s'ancida (Ercole, Achille, Autonoe, Orillo)

08. Alcide. Achille. Achille (Chirone, Orillo)

09. Sofferenza, mio core (Erinda, Aristeo)

10. Aristeo che t'afflige (Esculapio, Aristeo, Erinda)

11. Riverito signor, qual duol t'opprime (Euridice, Aristeo)

12. Cielo, ch'ascolto (Orfeo, Aristeo, Euridice)

13. Chi geloso non è, non vive amante (Orfeo)

14. Vaghi fiori (Euridice, Erinda)

15. Qual improvviso lampo (Autonoe, Euridice, Erinda, Ninfe)

16. Che rotta fè. Che egizia (Aristeo, Achille, Autonoe, Erinda, Ninfe)

17. Son amante, ma sfortunato (Aristeo)

18. Lieta, amiche, respiro. A fè credei (Erinda)

ATTO 2

19. Sei morto al contento (Orfeo)

20. Anco Orfeo si querela (Esculapio, Orfeo)

21. Misero Orfeo, sono i sospiri e i pianti (Esculapio)

22. Signor, con troppo fretta (Orillo, Chirone, Erinda)

23. Non ho core per mirar (Erinda)

CD2

01. Ecco il sol che m'innamora (Aristeo, Euridice, Autonoe, Orfeo)

02. Tu mi tradisti, amor (Aristeo)

03. Io vi stringo, amici, al petto (Esculapio, Ercole, Achille)

04. Aita (Euridice, Orfeo, Ercole, Achille, Esculapio)

05. Nobili eroi (Autonoe, Ercole, Achille)

06. Pur v'ho colti, o lascivi, in can si porta (Chirone, Ercole, Achille)

07. Crudel, tu m'abbandoni (Erinda, Orillo)

08. Doni chi vuol goder (Erinda)

09. Udisti, a la tua destra (Orfeo, Orillo)

10. Querce annose, piante ombrose (Euridice, Orillo)

11. Ferma, bella cagion de' miei sospiri (Aristeo, Euridice, Orillo)

12. Crudo serpe, che spietato (Aristeo)

13. Ferma Aristeo, che tenti (Bacco, Aristeo)

ATTO 3

14. Sempre dolente (Orfeo)

15. Signor (Orillo, Orfeo)

16. Scelerato Aristeo (Orfeo)

17. Orfeo tu dormi (Euridice, Orfeo)

18. Cessa omai di lacrimar (Erinda, Aristeo)

19. Aristeo. Mio crudel (Autonoe, Aristeo, Erinda)

20. Io sprezzata. Io schernita (Autonoe)

21. Dov'è (Esculapio, Orillo)

22. Vieni, vieni signora (Orillo, Autonoe, Ercole, Achille)

23. Tempo è di studio, Alcide, Achille (Chirone, Orillo)

24. Orfeo, vincesti (Pluto, Orfeo)

25. Numi, che veggio (Euridice, Orfeo)

26. Misero me, che oprai (Orfeo)

27. Bella Autonoe, chi t'offese perira (Achille, Autonoe)

28. Del mio tradito onore (Autonoe, Aristeo, Erinda)

29. E questa è la vendetta (Achille, Tetide, Autonoe, Aristeo, Erinda)

Born in Venice, Antonio Sartorio (1630-1680) composed 14 operas. He often made the long journey from Hanover, where he held the post of Maestro di Capella to the Duke of Brunswick, to compose and present new operas in his native city and recruit musicians for the German court. He is credited with introducing Italian opera to the Hanover court in 1672. Sartorio finally returned to Venice to be Maestro at St Mark’s where he composed sacred music, albeit not as much as the renowned Coffi might have been expected of him in that position.

Judging by this work, two-and-a-half hours long, with almost 50 arias (all brief) and a duet or two, he was a popularist. Clearly not wishing to burden his audience with another sad tale of Orfeo–which had been treated often, even by then–Sartorio and his librettist, Aurelio Aureli (1652-1708), opted to juice up the story, adding a half-dozen characters, some of them comic, and bending the story in such a way that the opera has a happy ending–although that happy ending has nothing to do with Orfeo, who disappears 10 minutes earlier. L'orfeo was premiered in Venice during the 1672-73 carnival season. Both the text and the music are typical of the authors, with complex sub-plots, ten scene changes, six ballets (not included here but in the Venetian score). It is a characteristic, but not particularly distinguished, example of Venetian opera of the second half of the 17th Century.

Aureli transformed the myth so that Orpheus is no longer the heroic lover prepared to travel to Hades to reclaim his beloved Euridice, but a husband whose chief passion is jealousy, so strong that he plots the death of his wife! Even her second death fails to move Orpheus for long although it inspires a fully fledged lament, after which he quickly resigns himself to living without her and, foreswearing all womanhood, he simply disappears. This allows the invented sub-plots to unravel to the conventional happy ending.

Sartorio’s setting of the text reflects his Venetian background and the heritage of Monteverdi and Cavalli. However, the recitatives, the core of Monteverdian operatic expression are replaced by arias of which L’Orfeo contains over 50, with each of the 10 characters given opportunity to express feelings directly to the audience in one or more monologue scenes. These scenes usually consist of two contrasting arias separated by a passage of recitative.

The distorted plot keeps the love between Orfeo and Euridice, but adds Aristeo, Orfeo’s brother, who also loves Euridice. Also in the mix are a princess (dressed as a Gypsy), Autonoe, who unrequitedly loves Aristeo; Euscalopio, a philosopher who muses on the silliness of love; two hunks–Achilles and Hercules (sorry, wrong myth, but who cares–we’re keeping the Venetians happy and paying), who are students of the centaur(!) Chiron and who fall for Autonoe; a shepherd, Orillo, who also finds Autonoe dazzling; and Erinda, an old nurse who is Aristeo’s foster-mother, and who lusts after Orillo.

Orfeo becomes wildly jealous of Euridice when he overhears her paying attention to the half-mad Aristeo and he asks Orillo to kill her(!); but before Orillo can carry out the dastardly deed Euridice goes for a walk and gets bitten by the (familiar) snake and dies. Orfeo goes to the underworld and Pluto gives in with the hitch we all know (don’t look back), which Orfeo can’t live up to. Euridice dies again and Orfeo sings a lament renouncing feminine beauty and goes away. Completely. Autonoe somehow convinces Achilles to kill Aristeo, but in the end, with Erinda asking for mercy, Aristeo is spared and he and Autonoe rekindle their love. Achilles’ mother, the sea-goddess Thetis, shows up (on the shore in Thrace) and admonishes him for being a wimp and whisks him away in a final aria. The opera closes with a two-minute aria by a minor character-ex-machina.

Judging by this work, two-and-a-half hours long, with almost 50 arias (all brief) and a duet or two, he was a popularist. Clearly not wishing to burden his audience with another sad tale of Orfeo–which had been treated often, even by then–Sartorio and his librettist, Aurelio Aureli (1652-1708), opted to juice up the story, adding a half-dozen characters, some of them comic, and bending the story in such a way that the opera has a happy ending–although that happy ending has nothing to do with Orfeo, who disappears 10 minutes earlier. L'orfeo was premiered in Venice during the 1672-73 carnival season. Both the text and the music are typical of the authors, with complex sub-plots, ten scene changes, six ballets (not included here but in the Venetian score). It is a characteristic, but not particularly distinguished, example of Venetian opera of the second half of the 17th Century.

Aureli transformed the myth so that Orpheus is no longer the heroic lover prepared to travel to Hades to reclaim his beloved Euridice, but a husband whose chief passion is jealousy, so strong that he plots the death of his wife! Even her second death fails to move Orpheus for long although it inspires a fully fledged lament, after which he quickly resigns himself to living without her and, foreswearing all womanhood, he simply disappears. This allows the invented sub-plots to unravel to the conventional happy ending.

Sartorio’s setting of the text reflects his Venetian background and the heritage of Monteverdi and Cavalli. However, the recitatives, the core of Monteverdian operatic expression are replaced by arias of which L’Orfeo contains over 50, with each of the 10 characters given opportunity to express feelings directly to the audience in one or more monologue scenes. These scenes usually consist of two contrasting arias separated by a passage of recitative.

The distorted plot keeps the love between Orfeo and Euridice, but adds Aristeo, Orfeo’s brother, who also loves Euridice. Also in the mix are a princess (dressed as a Gypsy), Autonoe, who unrequitedly loves Aristeo; Euscalopio, a philosopher who muses on the silliness of love; two hunks–Achilles and Hercules (sorry, wrong myth, but who cares–we’re keeping the Venetians happy and paying), who are students of the centaur(!) Chiron and who fall for Autonoe; a shepherd, Orillo, who also finds Autonoe dazzling; and Erinda, an old nurse who is Aristeo’s foster-mother, and who lusts after Orillo.

Orfeo becomes wildly jealous of Euridice when he overhears her paying attention to the half-mad Aristeo and he asks Orillo to kill her(!); but before Orillo can carry out the dastardly deed Euridice goes for a walk and gets bitten by the (familiar) snake and dies. Orfeo goes to the underworld and Pluto gives in with the hitch we all know (don’t look back), which Orfeo can’t live up to. Euridice dies again and Orfeo sings a lament renouncing feminine beauty and goes away. Completely. Autonoe somehow convinces Achilles to kill Aristeo, but in the end, with Erinda asking for mercy, Aristeo is spared and he and Autonoe rekindle their love. Achilles’ mother, the sea-goddess Thetis, shows up (on the shore in Thrace) and admonishes him for being a wimp and whisks him away in a final aria. The opera closes with a two-minute aria by a minor character-ex-machina.

![Jamaican Jazz Orchestra - Rain Walk (2019) [Hi-Res] Jamaican Jazz Orchestra - Rain Walk (2019) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/21/snzv0mdiaf2dg21tiqrm87jaq.jpg)

![Santi Vega - Un Instante Infinito (2025) [Hi-Res] Santi Vega - Un Instante Infinito (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/19/xkxaonr6q5o8ydwyf3z1c8tp5.jpg)