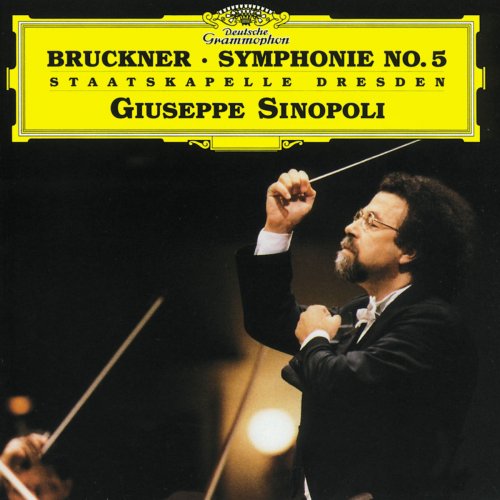

Staatskapelle Dresden - Bruckner: Symphony No.5 (2001)

Artist: Staatskapelle Dresden

Title: Bruckner: Symphony No.5

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: Deutsche Grammophon / Universal Music

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 76:39 min

Total Size: 346 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Bruckner: Symphony No.5

Year Of Release: 2001

Label: Deutsche Grammophon / Universal Music

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 76:39 min

Total Size: 346 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Symphony No.5 in B flat major : 1. Introduction: Adagio - Allegro

02. Symphony No.5 in B flat major : 2. Sehr langsam

03. Symphony No.5 in B flat major : 3. Scherzo: Molto vivace - Trio

04. Symphony No.5 in B flat major : 4. Finale: Adagio - Allegro molto

Publishers publish ‘study’ scores, but no marketing guru has ever come up with the idea of the ‘study’ recording. They exist, of course: recordings which do us the singular honour of providing an interpretation while at the same time allowing us to hear all the notes. This doesn’t suit every piece of music (‘Gentleman,’ Richard Strauss once said, ‘Give me an impression of the music!’), nor does it suit all listeners. How will this new Dresden Bruckner Fifth be listened to? Analytically, score in hand, or half-waking in a favourite armchair waiting for the Grail to descend? I mention these possibilities because this is a study recording par excellence, as close as we have come on record to being provided with a sound facsimile of the symphony’s printed page.

Such an undertaking requires immense discipline from the orchestra, the balance engineer (Klaus Hiemann) and the conductor. On this form the Staatskapelle Dresden have no peer. The sound is characterful, the ensemble exact, the concentration absolute. There must be a quarter of a million notes in this symphony and we hear practically all of them more or less flawlessly delivered. (A hair’s-breadth wobble by a player it would be invidious to identify is an event in itself.)

I described the engineering on Sinopoli’s Bruckner Ninth as ‘intensely concentrated: not cold as such but fiercely analytical’. Whether that entirely suited the Ninth is a moot point. The Fifth, though, is very well suited, for it is arguably the most intricately crafted of all Bruckner’s symphonies. The myriad ways in which themes combine and recombine is a source of endless fascination, albeit one hitherto best examined in the silence of the study.

Sinopoli is here more the alpha-quality Kapellmeister than the Bruckner ‘interpreter’. The text is his passion; his trust in it is absolute, his patience immense. The first movement is one of Bruckner’s most subtle and elusive. What I had not realised until now is how much of it is marked to be delivered in an undertone, with p, pp, and ppp the principal markings. Cynics will argue that Bruckner wrote these in because he did not trust the orchestras and conductors of his time, a theory Sinopoli gives us every reason to doubt.

After the enigma that is the first movement, Sinopoli senses a somewhat easier, more sunlit mood in the Adagio, the limbo-like moments of stasis notwithstanding. He is wary, however, of what some conductors see as the Upper Austrian folksiness of the Scherzo. ‘A formidable human power directly faced with heedless gaiety’ is how Robert Simpson sums up this music, exactly how Sinopoli appears to see it, too.

The finale resolves fugue, chorale and a host of earlier considerations into a glorious home-coming, a process greatly helped here by Sinopoli’s refreshingly swift, clear, beautifully integrated treatment of the main exposition. How splendidly this helps clarify and energise the argument later on! There is here an inevitability about the proceedings that has everything to do with the performance (the orchestra, in the tumultuous final pages, is supremely poised and perfectly balanced), without the performance in any way drawing attention to itself. It is Bruckner and the impeccable logic of his musical thinking we are listening to (and very moving it proves to be).

Such an undertaking requires immense discipline from the orchestra, the balance engineer (Klaus Hiemann) and the conductor. On this form the Staatskapelle Dresden have no peer. The sound is characterful, the ensemble exact, the concentration absolute. There must be a quarter of a million notes in this symphony and we hear practically all of them more or less flawlessly delivered. (A hair’s-breadth wobble by a player it would be invidious to identify is an event in itself.)

I described the engineering on Sinopoli’s Bruckner Ninth as ‘intensely concentrated: not cold as such but fiercely analytical’. Whether that entirely suited the Ninth is a moot point. The Fifth, though, is very well suited, for it is arguably the most intricately crafted of all Bruckner’s symphonies. The myriad ways in which themes combine and recombine is a source of endless fascination, albeit one hitherto best examined in the silence of the study.

Sinopoli is here more the alpha-quality Kapellmeister than the Bruckner ‘interpreter’. The text is his passion; his trust in it is absolute, his patience immense. The first movement is one of Bruckner’s most subtle and elusive. What I had not realised until now is how much of it is marked to be delivered in an undertone, with p, pp, and ppp the principal markings. Cynics will argue that Bruckner wrote these in because he did not trust the orchestras and conductors of his time, a theory Sinopoli gives us every reason to doubt.

After the enigma that is the first movement, Sinopoli senses a somewhat easier, more sunlit mood in the Adagio, the limbo-like moments of stasis notwithstanding. He is wary, however, of what some conductors see as the Upper Austrian folksiness of the Scherzo. ‘A formidable human power directly faced with heedless gaiety’ is how Robert Simpson sums up this music, exactly how Sinopoli appears to see it, too.

The finale resolves fugue, chorale and a host of earlier considerations into a glorious home-coming, a process greatly helped here by Sinopoli’s refreshingly swift, clear, beautifully integrated treatment of the main exposition. How splendidly this helps clarify and energise the argument later on! There is here an inevitability about the proceedings that has everything to do with the performance (the orchestra, in the tumultuous final pages, is supremely poised and perfectly balanced), without the performance in any way drawing attention to itself. It is Bruckner and the impeccable logic of his musical thinking we are listening to (and very moving it proves to be).

![Tomasz Stanko, Polskie Radio - Jazz Rock Company: Live at Akwarium (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 6/6) (2025) [Hi-Res] Tomasz Stanko, Polskie Radio - Jazz Rock Company: Live at Akwarium (Polish Radio Sessions vol. 6/6) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765796554_cover.jpg)