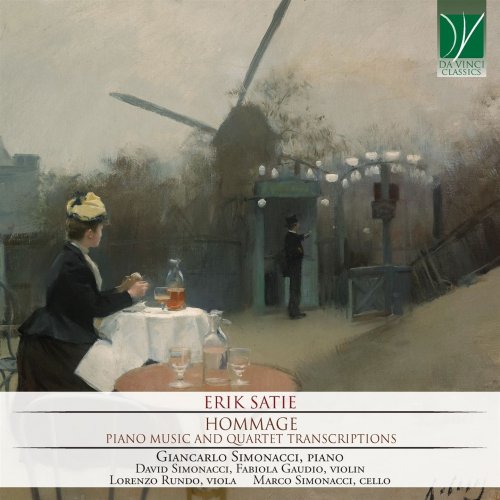

Giancarlo Simonacci, David Simonacci, Fabiola Gaudio, Lorenzo Rundo, Marco Simonacci - Erik Satie - Hommage (Piano Music and Quartet Transcription) (2020)

Artist: Giancarlo Simonacci, David Simonacci, Fabiola Gaudio, Lorenzo Rundo, Marco Simonacci

Title: Erik Satie - Hommage (Piano Music and Quartet Transcription)

Year Of Release: 2020

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless

Total Time: 00:54:59

Total Size: 189 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Erik Satie - Hommage (Piano Music and Quartet Transcription)

Year Of Release: 2020

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Piano

Quality: flac lossless

Total Time: 00:54:59

Total Size: 189 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

---------

01. Gnossiennes: No. 1, Lent

02. Gnossiennes: No. 2, Avec étonnement

03. Gnossiennes: No. 3, Lent

04. Gnossiennes: No. 4, Lent

05. Gnossiennes: No. 5, Modéré

06. Gnossiennes: No. 6, Avec conviction et avec une tristesse rigoureuse

07. Choral pour quatuor à cordes

08. Douze petits chorals: No. 1

09. Douze petits chorals: No. 2

10. Douze petits chorals: No. 3

11. Douze petits chorals: No. 4

12. Douze petits chorals: No. 5

13. Douze petits chorals: No. 6a

14. Douze petits chorals: No. 6b

15. Douze petits chorals: No. 7

16. Douze petits chorals: No. 8

17. Douze petits chorals: No. 9

18. Douze petits chorals: No. 10

19. Douze petits chorals: No. 11

20. Douze petits chorals: No. 12

21. Gnossiennes: No. 1, Lent (Transcr. pour quatuor à cordes)

22. Gnossiennes: No. 2, Avec étonnement (Transcr. pour quatuor à cordes)

23. Gnossiennes: No. 3, Lent (Transcr. pour quatuor à cordes)

24. Gnossiennes: No. 6, Avec conviction et avec une tristesse rigoureuse (Transcr. pour quatuor à cordes)

25. Six pièces de la période 1906-1913: No. 1, Désespoir agréable

26. Six pièces de la période 1906-1914: No. 2, Effronterie

27. Six pièces de la période 1906-1915: No. 3, Poésie

28. Six pièces de la période 1906-1916: No. 4, Prélude canin

29. Six pièces de la période 1906-1917: No. 5, Profondeur

30. Six pièces de la période 1906-1918: No. 6, Songe creux

31. Six pièces de la période 1906-1919: No. 1, Désespoir agréable (Transcr. pour quatuor à cordes)

32. Six pièces de la période 1906-1920: No. 6, Songe creux (Transcr. pour quatuor à cordes)

The transcription of music is always an act of love. Indeed, the choice of transferring a piece of music into a timbral shape different from the original springs from a deep emotional involvement, generated, in turn, by a true interpenetration of the musical object chosen for this transformation. Therefore, one’s decision to revisit the original texture by employing new timbral parameters is dictated by a powerful desire to penetrate into the most intimate peculiarities of the work one loves.

These transcriptions, for string quartet, of four of the six Gnossiennes and of the first (Désespoir agréable) and sixth (Songe creux) pieces from the collection Six pièces de la période 1906-1913 (this title is not by Satie), are some of the fruits of my wanderings in the unfathomable and fascinating planet of the French master’s music.

The string quartet is a habitat very different from the piano; however, here it is possible to differentiate (possibly with a subtler evidence) among several games of references, allusions, and of slight emotional exchanges.

My own Choral pour quatuor à cordes was written in 2016, on the occasion of Satie’s 150th birthday. The sixth of Satie’s Douze petits chorals undergoes twenty elaborations, under the viewpoints of melody and counterpoint. Through a renewed share of dynamics and phrasing, a self-standing, great Choral takes form; only in the conclusion, Satie’s Petit Choral no. 6b appears in its original shape.

Note by Giancarlo Simonacci

One of the main tenets of the Romantic view of music is that it expresses something; and this “something” most often is identified as the composer’s feelings, emotions or affections. And while it is extremely hard to positively define the figure and music of Erik Satie (1866-1925), it is probably much easier to conceive him as the negation of this tenet. In the Romantic view, the expression of feelings through music was made possible by the creation of tensions and distensions, which build up a narrative of musical events, leading the listener to formulate sets of expectations (which may translate into desires and wishes for music to take a certain shape). As in all other forms of organized narration, the logic underlying Romantic music is a form of belief in some kind of “Providence”: the ordering of the musical material with a finality, a goal, a telos is a symbol for the order of all events in time and history, and this ordering is thought of as graspable, at least through intuition.

Satie’s music takes a deliberate stance against this all. His works and aesthetics have been defined as pre-minimalist, pre-ambient music, and many other “pre’s”; however, basically, his music is the embodiment of a powerful nihilism. It may well be summed up by the title of one of his pieces recorded here, “Songe creux”, where “creux” may mean hollow, void or empty. It is almost a musical parallel to T. S. Eliot’s Hollow Men and to the worldview they embody.

Satie’s biography bears witness to his unbridled personality, and to the resistance it offers to all attempts at neat classification. For example, Satie was expelled twice from the Paris Conservatoire, and consequently rebelled against academicism, almost priding himself of his mostly self-taught accomplishments; however, as an adult, he unexpectedly undertook a course in counterpoint at one of the most traditionalist music institutions of the French capital, the Schola Cantorum directed by Vincent d’Indy. Satie earned his life as a cabaret pianist, and yet he (for a while) befriended and inspired many of the greatest French composers of the era (including Debussy, Ravel, and the so-called Groupe des Six), who felt the subtle and undefinable fascination of this elusive artist. He disdainfully mocked the musical establishment, and yet was painfully grieved when it failed to understand and appreciate him. He wrote musical and literary nonsense works, while embarking in pseudo-mystical undertakings and experiences.

The programme in this CD bears witness to many aspects of the multifaceted personality and artistic output of this unique musician. The Gnossiennes are among Satie’s best known works, and are also frequently performed in contexts outside the concert stage. Their very title is a conundrum and has elicited numerous speculations by scholars and researchers. The two most likely hypotheses connect the word either to the Greek gnosis, the “knowledge” pursued by the gnostic sects aiming at the handing down of hidden wisdom, or to Knossos with its labyrinth. In either case (and in both, if the double allusion was intended by Satie), the underlying concept is that of a tortuous, undisclosed and restricted itinerary, penetrating deeply inside some kind of mysterious entity. Satie’s music corresponds closely to this view. The first three Gnossiennes, which were published (not yet as a set) in 1893, and reprinted as a collection twenty years later, set themselves free from many established rules of musical orthography, including the use of bar lines and measures. However (and characteristically), this seeming rhythmic freedom is in turn fictional, since – to a higher or lesser degree – the Gnossiennes display a considerable rhythmical fixity, far exceeding that of many Classical pieces. Indeed, the hypnotic regularity of the beat and the static organization of harmony and melody are among the distinctive features through which Satie manages to refute the dynamics of tension and distension which gave “life” and purpose to Romantic music.

The remaining three Gnossiennes were published posthumously, and did not bear this title in the available sources by the composer; this spurious label, which is rather convincing from the stylistic viewpoint, is nonetheless debatable especially since it suggests a unity of concept which is in fact missing in Satie’s documented activity. The Gnossiennes seem also to allude to dance-rhythms and styles, though, once more, this is a mere conjecture; musically, they suggest references to a stylized and mythical past of Grecian marble-like purity (not unlike Debussy’s Danseuses de Delphes), while deliberately infecting it with freer and more seductive embellishments of a Middle-Eastern flavour. All of this, of course, is observed from far away, with a detachment which attempts at hiding a deep nostalgia, almost a longing for a time when music was still allowed to be “expressive” and touching.

A similar nostalgia is found in the Douze petits chorals, twelve short Chorale harmonisations dating from Satie’s years at the Schola cantorum. They resemble academic exercises, sung prayers and, sometimes, ironic deformations of the traditional harmonic structures, and yet cannot be simply identified as any of the above. Here too the musical surface seems to reveal an immediately denied desire for the musical world where chords “knew” how to follow each other, and music “knew” how to express the common religious feeling of a community. It is not by chance that these Chorales inspired John Cage’s Chorals: Cage’s admiration for Satie is well known, though, possibly, the American composer acknowledged only Satie’s satire (if the word-pun is allowed), perhaps ignoring the pain it attempted to conceal. For Cage, the “emptiness” of a nihilistic world was already a component of the contemporaneous zeitgeist; for Satie, it still had the bitter feeling of a newly discovered anguish.

And this is precisely what is declared, rather clearly, in the titles and content of the other pieces recorded here. Under the collective (and once more apocryphal) label of Six pièces de la période 1906-1913, we find such works as the “enjoyable despair”, the already mentioned “hollow dream”, a “canine prelude” but also, significantly, a “poem”. Indeed, Poésie (published in 1968 with Effronterie as Deux choses) can be interpreted as Satie’s anticipation of yet another composer; in this case, the comparison is daring indeed, as it involves a musician whose worldview, musical style and personality were antithetic to Satie’s, i.e. Olivier Messiaen. While the younger composer favoured magniloquence and the elder is known for his minimalist style; while Messiaen was a devout Catholic and Satie’s religious beliefs are contradictory and unorthodox; while Messiaen lived a very orderly life, animated by ornithology and theology, and Satie’s was a very chaotic existence; nonetheless, arguably, Satie’s influence extended even to this most unlikely of his disciples. Messiaen was fascinated by symbolist poetry, and was famous for his synesthetic experiences which led him to attribute colours to sounds, chords and harmonies; and, in this Poésie by Satie, the expression indications are replaced by such puzzling labels as “rather blue”, “whiter”, and – fascinatingly, given Messiaen’s religious penchant – “cloîtrement”, which may be translated as “cloisterly”. Of course, Satie’s labels must always be taken with a grain of salt; the “infectious irony” (“avec une ironie contagieuse”) found in Désespoir agréable is hardly discernible from the très triste (“very sad”) which preceded it by a few bars.

Love it or hate it, Satie’s music is so unique and original, so recognizable in spite of its mishmash of inspirations and of its composer’s chaotic life, that it represents one of the most idiosyncratic creations of its era. Many of Satie’s most famous and representative works are written for the piano, and this destination is rather unsurprising: not only was Satie a pianist, but the possibility of achieving a kind of expressive neutrality when playing the piano’s black and white keys seems to be particularly well suited for the inexpressive quality of much of Satie’s music. In spite of this, several musicians have attempted to “colour” Satie’s piano pieces, following in the footsteps of Debussy who orchestrated two of the Gymnopédies. The transcriptions for string quartet recorded here, and juxtaposed to Satie’s original in a game reminiscent of Warhol’s art, cast a new light on these pieces: on the one hand, different from an orchestration proper, the versions for string quartet feature an ensemble with a certain homogeneity of sound; on the other, the warmth of the strings’ sound encourages the listener to notice the “human” (and touching) quality of Satie’s music – to hear, in other words, that nostalgia which Satie tried to conceal behind the veil of irony.