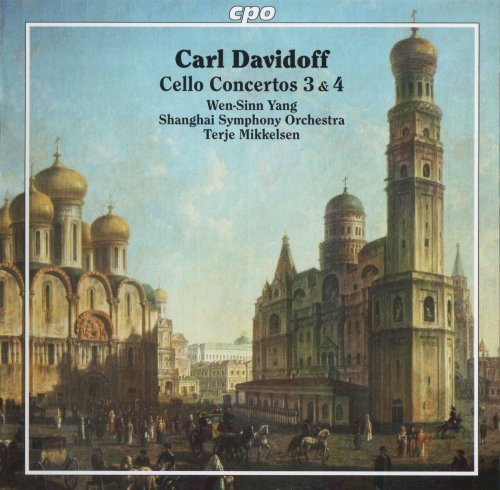

Wen-Sinn Yang - Carl Davidoff: Cello Concertos Nos. 3 & 4 (2010)

Artist: Wen-Sinn Yang

Title: Carl Davidoff: Cello Concertos Nos. 3 & 4

Year Of Release: 2010

Label: CPO

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:11:33

Total Size: 383 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Carl Davidoff: Cello Concertos Nos. 3 & 4

Year Of Release: 2010

Label: CPO

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 01:11:33

Total Size: 383 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

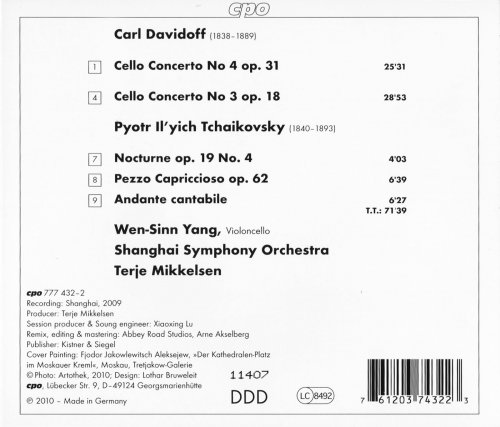

Carl Davidoff (1838-1889):

01. Concerto for cello & orchestra, No. 4 in E minor, Op. 31: Allegro [0:10:39.66]

02. Concerto for cello & orchestra, No. 4 in E minor, Op. 31: Lento [0:07:41.55]

03. Concerto for cello & orchestra, No. 4 in E minor, Op. 31: Finale. Vivace [0:07:11.09]

04. Concerto for cello &oOrchestra, No. 3 in D major, Op. 18: Allegro moderato [0:14:30.49]

05. Concerto for cello &oOrchestra, No. 3 in D major, Op. 18: Andante [0:06:51.22]

06. Concerto for cello &oOrchestra, No. 3 in D major, Op. 18: Allegro vivace [0:07:32.29]

Piotr Ilitch Tchaikovsky (1840-1893):

07. Nocturne, for cello & small orchestra (or piano) in D minor, Op. 19/4 [0:04:03.29]

08. Pezzo capriccioso, for cello & orchestra (or cello & piano) in B minor, Op. 62 [0:06:39.28]

09. Andante cantabile, for cello and string orchestra in D major (arr. of 2nd mvt. from String Quartet No.1) [0:06:27.25]

Performers:

Wen-Sinn Yang - cello

Shangai Symphony Orchestra

Terje Mikkelsen - conductor

Born in what is now part of Latvia, Carl Davidoff (1838–89) completed a degree in mathematics at the St. Petersburg University before he enrolled at the Leipzig Conservatory to study composition. He had been playing cello, however, since he was 12; after renowned cellist Friedrich Wilhelm Grutzmacher departed his post, Davidoff, at 22, was offered his cello professorship at the Leipzig Conservatory. In 1876, after internal squabbling among the administrators of the St. Petersburg Conservatory, Davidoff was appointed that institution’s director, no doubt to the displeasure of Tchaikovsky, who had been a candidate for the position. I suspect this was the irritant that caused Tchaikovsky to turn to Fitzenhagen instead of Davidoff for assistance with his Rococo Variations . The rest, as they say, is history. Davidoff, along with David Popper, became one of the most celebrated cellists of the second half of the 19th century, and was honored as the dedicatee of Dvo?ák’s famous concerto.

It’s not in the least far-fetched to draw parallels between Davidoff, the virtuoso cellist, and Wienawski (1835–80), the virtuoso violinist. Not only were they near contemporaries, but more significantly, at the invitation of Anton Rubinstein, Wieniawski moved to St. Petersburg, where he lived from 1860 to 1872, teaching violin in Rubinstein’s Russian Music Society. Davidoff had been teaching cello at the St. Petersburg Conservatory since 1863, so it’s almost certain that during Wieniawski’s years in the city the two men would have crossed paths.

The compositions written by both of them for their respective instruments represent a next phase in the development of the virtuoso concerto after Paganini. Hair-raising pyrotechnics and high-wire daredevil cadenzas still abound, but now there is at least some semblance of more serious, expansive concerted scores in which the orchestra plays more than a barrel-organ accompanimental role. Contrasting lyrical passages vie for attention more convincingly amid the miles of blistering runs up and down the fingerboard, joint-dislocating double-stops, bow-bending arpeggios, artificial harmonics, and flying staccato.

As music, I would tend to agree with Godell’s “of dubious value” judgment. But the technical innovations and challenges are not of dubious value, for they opened the door to works, like the cello concertos of Dvo?ák, Elgar, Shostakovich, Myaskovsky, and many others that would take those innovations for granted and make them an integral part of the composition.

Of such insignificance, apparently, are the three Tchaikovsky fillers on the disc that not a single word about them is to be found in eight pages of vanishingly small print by note author Eckhardt van den Hoogen who, nonetheless, finds it important to ramble on for a full page about Davidoff’s 1712 Stradivarius cello. So, to fill in the blank, Tchaikovsky’s Nocturne in C?-Minor has long been a favorite of cellists. It’s the fourth piece from the six Morceaux, op. 19, originally for solo piano. The Pezzo Capriccioso is an original piece for cello and orchestra written in 1887. Its title belies its depressive B-Minor mood, which is generally attributed to Tchaikovsky’s tending to a dying friend, Nikolay Kondratyev, who was nearing the end in his battle against syphilis. The Andante cantabile will of course be recognized as an arrangement for cello and orchestra of the second movement from Tchaikovsky’s D-Major String Quartet, op. 11.

At present, there does not appear to be any recorded competition for these two Davidoff concertos, so it’s good news that Wenn-Sinn Yang can be recommended without reservation to those who take pleasure in cello gymnastics of the most demanding kind. Yang never once loses composure, and even manages to play these extremely difficult works with a good deal of tonal beauty and, where the music allows it, with considerable emotional expressivity. Norwegian maestro Terje Mikkelsen, who studied under Mariss Jansons, and who has led the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra since 2006, is a conductor who made quite an impression on me with a recent recording he made with the Latvian National Symphony Orchestra for Sterling of two symphonies by Norwegian Romantic composer Eyvind Alnæs. I expect we will be hearing a lot more from Mikkelsen in the not-too-distant future.

In sum, this cpo release is an excellent recording, and one that may be strongly recommended to those with an appreciation for this type of repertoire. -- Jerry Dubins

It’s not in the least far-fetched to draw parallels between Davidoff, the virtuoso cellist, and Wienawski (1835–80), the virtuoso violinist. Not only were they near contemporaries, but more significantly, at the invitation of Anton Rubinstein, Wieniawski moved to St. Petersburg, where he lived from 1860 to 1872, teaching violin in Rubinstein’s Russian Music Society. Davidoff had been teaching cello at the St. Petersburg Conservatory since 1863, so it’s almost certain that during Wieniawski’s years in the city the two men would have crossed paths.

The compositions written by both of them for their respective instruments represent a next phase in the development of the virtuoso concerto after Paganini. Hair-raising pyrotechnics and high-wire daredevil cadenzas still abound, but now there is at least some semblance of more serious, expansive concerted scores in which the orchestra plays more than a barrel-organ accompanimental role. Contrasting lyrical passages vie for attention more convincingly amid the miles of blistering runs up and down the fingerboard, joint-dislocating double-stops, bow-bending arpeggios, artificial harmonics, and flying staccato.

As music, I would tend to agree with Godell’s “of dubious value” judgment. But the technical innovations and challenges are not of dubious value, for they opened the door to works, like the cello concertos of Dvo?ák, Elgar, Shostakovich, Myaskovsky, and many others that would take those innovations for granted and make them an integral part of the composition.

Of such insignificance, apparently, are the three Tchaikovsky fillers on the disc that not a single word about them is to be found in eight pages of vanishingly small print by note author Eckhardt van den Hoogen who, nonetheless, finds it important to ramble on for a full page about Davidoff’s 1712 Stradivarius cello. So, to fill in the blank, Tchaikovsky’s Nocturne in C?-Minor has long been a favorite of cellists. It’s the fourth piece from the six Morceaux, op. 19, originally for solo piano. The Pezzo Capriccioso is an original piece for cello and orchestra written in 1887. Its title belies its depressive B-Minor mood, which is generally attributed to Tchaikovsky’s tending to a dying friend, Nikolay Kondratyev, who was nearing the end in his battle against syphilis. The Andante cantabile will of course be recognized as an arrangement for cello and orchestra of the second movement from Tchaikovsky’s D-Major String Quartet, op. 11.

At present, there does not appear to be any recorded competition for these two Davidoff concertos, so it’s good news that Wenn-Sinn Yang can be recommended without reservation to those who take pleasure in cello gymnastics of the most demanding kind. Yang never once loses composure, and even manages to play these extremely difficult works with a good deal of tonal beauty and, where the music allows it, with considerable emotional expressivity. Norwegian maestro Terje Mikkelsen, who studied under Mariss Jansons, and who has led the Shanghai Symphony Orchestra since 2006, is a conductor who made quite an impression on me with a recent recording he made with the Latvian National Symphony Orchestra for Sterling of two symphonies by Norwegian Romantic composer Eyvind Alnæs. I expect we will be hearing a lot more from Mikkelsen in the not-too-distant future.

In sum, this cpo release is an excellent recording, and one that may be strongly recommended to those with an appreciation for this type of repertoire. -- Jerry Dubins

![Hugh Masekela - You Told Your Mama Not To Worry (2026) [Hi-Res] Hugh Masekela - You Told Your Mama Not To Worry (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772763505_wgq166vg6nqpm_600.jpg)

![Mike Casey - The Complete In The Before: Live at the Side Door (2026) [Hi-Res] Mike Casey - The Complete In The Before: Live at the Side Door (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/06/jhudb8a5ewf26xo1l0a9smyu2.jpg)

![VA - Women of Jazz '26 (2026) [Hi-Res] VA - Women of Jazz '26 (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772719876_cover.jpg)