Luca Fanfoni, Reale Concerto - Antonio Lolli: Violin Concertos (2007)

Artist: Luca Fanfoni, Reale Concerto

Title: Antonio Lolli: Violin Concertos

Year Of Release: 2007

Label: Dynamic

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 02:56:20

Total Size: 952 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Antonio Lolli: Violin Concertos

Year Of Release: 2007

Label: Dynamic

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 02:56:20

Total Size: 952 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

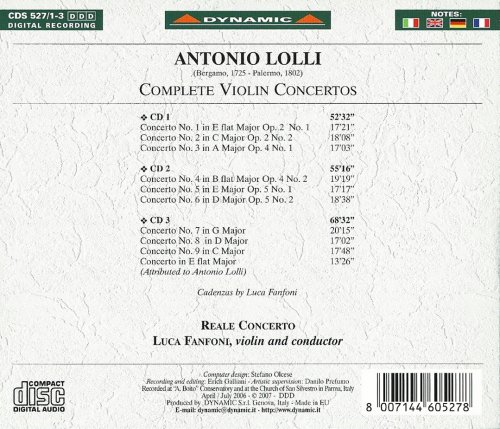

CD 1:

01. Violin Concerto No. 1 in E flat major, Op. 2-1- Allegro [0:07:10.00]

02. Violin Concerto No. 1 in E flat major, Op. 2-1- Adagio [0:03:40.00]

03. Violin Concerto No. 1 in E flat major, Op. 2-1- Allegro assai [0:06:31.00]

04. Violin Concerto No. 2 in C major, Op. 2-2- Andante [0:07:12.00]

05. Violin Concerto No. 2 in C major, Op. 2-2- Adagio [0:05:16.00]

06. Violin Concerto No. 2 in C major, Op. 2-2- Allegro [0:05:40.00]

07. Violin Concerto No. 3 in A major, Op. 4-1- Allegretto [0:07:06.00]

08. Violin Concerto No. 3 in A major, Op. 4-1- Andante [0:03:18.00]

09. Violin Concerto No. 3 in A major, Op. 4-1- Allegro [0:06:40.00]

CD 2:

01. Violin Concerto No. 4 in B flat major, Op. 4-2- Allegretto [0:08:16.02]

02. Violin Concerto No. 4 in B flat major, Op. 4-2- Adagio [0:04:54.00]

03. Violin Concerto No. 4 in B flat major, Op. 4-2- Allegro [0:06:09.11]

04. Violin Concerto No. 5 in E major, Op. 5-1- Andante [0:07:27.29]

05. Violin Concerto No. 5 in E major, Op. 5-1- Adagio [0:03:56.00]

06. Violin Concerto No. 5 in E major, Op. 5-1- Allegro [0:05:57.47]

07. Violin Concerto No. 6 in D major, Op. 5-2- Allegro [0:08:26.00]

08. Violin Concerto No. 6 in D major, Op. 5-2- Andante [0:03:30.00]

09. Violin Concerto No. 6 in D major, Op. 5-2- Allegro [0:06:43.00]

CD 3:

01. Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major- Allegro spiritoso [0:08:54.00]

02. Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major- Adagio cantabile [0:03:48.00]

03. Violin Concerto No. 7 in G major- Allegro [0:07:33.38]

04. Concerto No. 8 in D major, for violin, 2 oboes & 2 horns- Allegro moderato [0:06:58.00]

05. Concerto No. 8 in D major, for violin, 2 oboes & 2 horns- Largo [0:04:48.00]

06. Concerto No. 8 in D major, for violin, 2 oboes & 2 horns- Allegro [0:05:16.00]

07. Concerto No. 9 in C major, for violin & 2 horns- Allegro moderato [0:08:08.00]

08. Concerto No. 9 in C major, for violin & 2 horns- Andante [0:04:08.00]

09. Concerto No. 9 in C major, for violin & 2 horns- Rondò tempo di Minuetto [0:05:32.00]

10. Concerto for violin & 2 horns in E flat major- Moderato [0:06:18.00]

11. Concerto for violin & 2 horns in E flat major- Adagio [0:02:54.00]

12. Concerto for violin & 2 horns in E flat major- Allegro [0:04:15.00]

Performers:

Luca Fanfoni - violin and direction

Reale Concerto

Lolli has received relatively little attention in modern times. I haven’t, for example, been able to trace a single reference to him in the pages of MusicWeb International. Despite this he holds a rather prominent place in that line of Italian violin virtuosi which runs from a figure such as Biagio Marini through Corelli and Tartini to Paganini and Viotti. The musicologist Albert Mell has, not unreasonably, written of him that he “was from many points of view the most important violin virtuoso before Paganini” (Musical Quarterly, Vol. 44, 1958) and Simon McVeigh (in The Cambridge Companion to the Violin) has described him as “the archetypal travelling virtuoso”.

Lolli was born in Bergamo, at a date not precisely known. Nor do we know anything of his early musical training or associations. Real knowledge of him begins only with documents relating to his appointment as solo violinist in the Stuttgart Kapelle in 1758. From surviving correspondence it is clear that his friends and supporters included Padre Giovanni Battista Martini - could Lolli have studied with him in Bologna? - and Niccolò Jommelli. Lolli was based in Stuttgart until 1774, though he also toured and performed in many other parts of Europe during these years. He had a spectacular success in 1764, playing as a soloist at the Concerts Spirituels in Paris. The year before that he had met with considerable success in Vienna – Dittersdorf, who had been in Italy at the time, writes in his autobiography that on his return his older brother “could not say enough about the sensation caused everywhere by his playing”. From 1774 to 1777, and again from 1780-1784, Lolli worked in St. Petersburg as ‘concertmaster’, performing, composing and teaching. Not all his energies went into music, however. For a while at least he was numbered amongst the lovers of Catherine the Great – until warned off by the secret police, supposedly acting under instructions to kill him, stuff him and mount him in a display case!

While many admired his playing, and while his showmanship guaranteed plenty of popular success, there seem always to have been some who found his performances too ostentatiously showy and gimmicky. Salieri wrote of the “ravishing, magical energy of Lolli’s playing” at his best, but felt that, especially later in his career, he was prone to the excessive use of portamento. Other contemporaries talked of his playing in terms of eccentricity and oddity. In the booklet notes to the present CD Danilo Prefumo quotes Charles Burney’s observation that “so eccentric was his style of composition and execution, that he was regarded as a madman by most of his hearers. Yet I am convinced that in his lucid intervals he was, in a serious style, a very great, expressive, and admirable performer. In his freaks nothing can be imagined so wild, grotesque, and even ridiculous as his compositions and performances”. It should be remembered, however, that Burney was writing after hearing a performance in 1785, when Lolli seems to have been past his best and increasingly given to attracting attention by his ability to use his instrument to imitate a variety of improbable sounds, such as bagpipes, the crowing of a cock and the barking of a dog.

We don’t know what music Burney heard him play in 1785. It is hard to believe that it can have been the concertos heard on these discs, to which no one, surely, would apply the adjective eccentric. These, surely, are examples of what Burney thought of as his “serious style”. There are no farmyard impressions to be heard here. All of the concertos are in three movements, and in the quicker movements there is much that is pretty orthodox galant style. There are substantial technical demands, since the soloist is required to spend a good deal of time at the higher end of the fingerboard and there are many double-stopped passages. But this never seems to be mere bravura – it comes closest to being so in the first two concertos. But even here there is a certain (admittedly not exceptionally individual) poetry, and in almost all of the slow central movements there is some attractively lyrical writing. But, in truth, this is, for the most part, pleasant, rather than dazzling music, very much of its time. If it was with these concertos that Lolli wowed his audiences he must, one presumes, have played with greater freedom, with more sheer self-display, than the excellent Luca Fanfoni allows himself. Fanfoni plays throughout with great assurance and control, with lucid phrasing and purity of tone. I wonder, indeed, if he doesn’t play too ‘correctly’, given what we know (or think we know) about Lolli’s performance strategies?

Lolli was a man addicted to gambling, who thereby lost much of the fortune he had acquired as a virtuoso. Perhaps there was more ‘gambling’ in his playing than our contemporary expectations encourage? Or, on the other hand, should we assume that – as both Salieri and Burney seem to imply – that there was a serious, ‘straight’ side to Lolli and, on the other hand, a vulgarising side, ready to put on a freak show for those best satisfied by such? In that case, one has to say that Lolli the serious composer was, on the evidence of these concertos, less distinguished than Lolli the virtuoso.

One slight puzzle remains. In addition to the nine published concertos by Lolli, Fantoni and his ensemble play an additional concerto apparently discovered in Dubrovnik by the soloist. On what grounds he attributes it to Lolli we are not told. Even Prefumo, in his notes, comments that “the authenticity of this concerto, whose writing and style are significantly different from those of the previous nine concertos, must at present be considered doubtful”.

All in all, this is a useful and pleasant set, a valuable documentation of an unduly neglected figure. Yet, in all honesty, it may not be one that the listener rushes to take from the shelves all that often. Fanfoni’s evident talents might, dare one say it, have been employed on more substantial materials. -- Glyn Pursglove

Lolli was born in Bergamo, at a date not precisely known. Nor do we know anything of his early musical training or associations. Real knowledge of him begins only with documents relating to his appointment as solo violinist in the Stuttgart Kapelle in 1758. From surviving correspondence it is clear that his friends and supporters included Padre Giovanni Battista Martini - could Lolli have studied with him in Bologna? - and Niccolò Jommelli. Lolli was based in Stuttgart until 1774, though he also toured and performed in many other parts of Europe during these years. He had a spectacular success in 1764, playing as a soloist at the Concerts Spirituels in Paris. The year before that he had met with considerable success in Vienna – Dittersdorf, who had been in Italy at the time, writes in his autobiography that on his return his older brother “could not say enough about the sensation caused everywhere by his playing”. From 1774 to 1777, and again from 1780-1784, Lolli worked in St. Petersburg as ‘concertmaster’, performing, composing and teaching. Not all his energies went into music, however. For a while at least he was numbered amongst the lovers of Catherine the Great – until warned off by the secret police, supposedly acting under instructions to kill him, stuff him and mount him in a display case!

While many admired his playing, and while his showmanship guaranteed plenty of popular success, there seem always to have been some who found his performances too ostentatiously showy and gimmicky. Salieri wrote of the “ravishing, magical energy of Lolli’s playing” at his best, but felt that, especially later in his career, he was prone to the excessive use of portamento. Other contemporaries talked of his playing in terms of eccentricity and oddity. In the booklet notes to the present CD Danilo Prefumo quotes Charles Burney’s observation that “so eccentric was his style of composition and execution, that he was regarded as a madman by most of his hearers. Yet I am convinced that in his lucid intervals he was, in a serious style, a very great, expressive, and admirable performer. In his freaks nothing can be imagined so wild, grotesque, and even ridiculous as his compositions and performances”. It should be remembered, however, that Burney was writing after hearing a performance in 1785, when Lolli seems to have been past his best and increasingly given to attracting attention by his ability to use his instrument to imitate a variety of improbable sounds, such as bagpipes, the crowing of a cock and the barking of a dog.

We don’t know what music Burney heard him play in 1785. It is hard to believe that it can have been the concertos heard on these discs, to which no one, surely, would apply the adjective eccentric. These, surely, are examples of what Burney thought of as his “serious style”. There are no farmyard impressions to be heard here. All of the concertos are in three movements, and in the quicker movements there is much that is pretty orthodox galant style. There are substantial technical demands, since the soloist is required to spend a good deal of time at the higher end of the fingerboard and there are many double-stopped passages. But this never seems to be mere bravura – it comes closest to being so in the first two concertos. But even here there is a certain (admittedly not exceptionally individual) poetry, and in almost all of the slow central movements there is some attractively lyrical writing. But, in truth, this is, for the most part, pleasant, rather than dazzling music, very much of its time. If it was with these concertos that Lolli wowed his audiences he must, one presumes, have played with greater freedom, with more sheer self-display, than the excellent Luca Fanfoni allows himself. Fanfoni plays throughout with great assurance and control, with lucid phrasing and purity of tone. I wonder, indeed, if he doesn’t play too ‘correctly’, given what we know (or think we know) about Lolli’s performance strategies?

Lolli was a man addicted to gambling, who thereby lost much of the fortune he had acquired as a virtuoso. Perhaps there was more ‘gambling’ in his playing than our contemporary expectations encourage? Or, on the other hand, should we assume that – as both Salieri and Burney seem to imply – that there was a serious, ‘straight’ side to Lolli and, on the other hand, a vulgarising side, ready to put on a freak show for those best satisfied by such? In that case, one has to say that Lolli the serious composer was, on the evidence of these concertos, less distinguished than Lolli the virtuoso.

One slight puzzle remains. In addition to the nine published concertos by Lolli, Fantoni and his ensemble play an additional concerto apparently discovered in Dubrovnik by the soloist. On what grounds he attributes it to Lolli we are not told. Even Prefumo, in his notes, comments that “the authenticity of this concerto, whose writing and style are significantly different from those of the previous nine concertos, must at present be considered doubtful”.

All in all, this is a useful and pleasant set, a valuable documentation of an unduly neglected figure. Yet, in all honesty, it may not be one that the listener rushes to take from the shelves all that often. Fanfoni’s evident talents might, dare one say it, have been employed on more substantial materials. -- Glyn Pursglove

![Black Viiolet - Dark Blue (2026) [Hi-Res] Black Viiolet - Dark Blue (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771144440_cover.jpg)