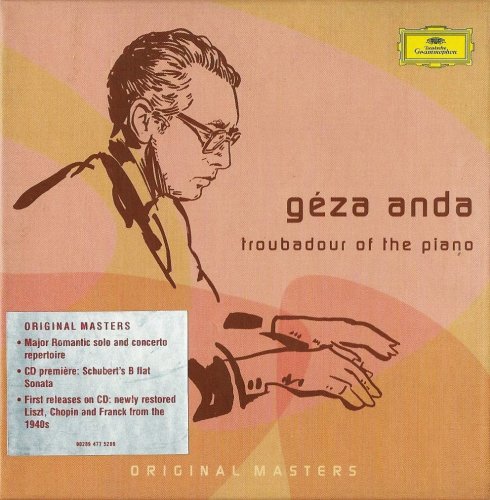

Géza Anda - Troubadour Of The Piano (5CD) (2005)

Artist: Géza Anda

Title: Troubadour Of The Piano

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 06:27:03

Total Size: 1.7 Gb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Troubadour Of The Piano

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: Deutsche Grammophon

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 06:27:03

Total Size: 1.7 Gb

WebSite: Album Preview

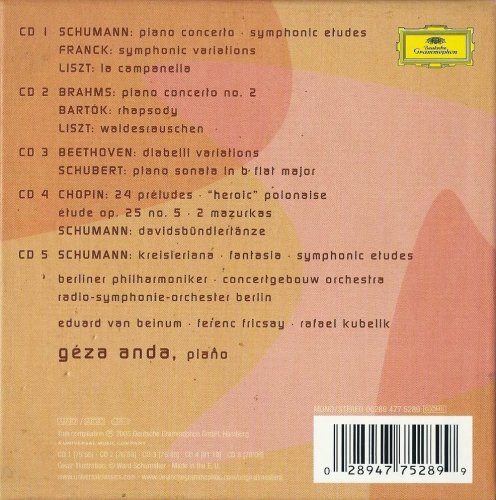

CD 1:

Robert Schumann (1810-1856):

Piano Concerto in A minor op.54

Symphonic Etudes op.13

César Franck (1822-1890):

Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra

Franz Liszt (1811-1886):

Etudes d'exécution transcendentes - La Campanella S 140 No.3

Berliner Philharmoniker

Concertgebouw Orchestra

Rafal Kubelik - conductor

Eduard van Beinum - conductor

CD 2:

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897):

Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No.2 in B flat major op.83

Béla Bartók (1881-1945):

Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra SZ 27

Franz Liszt (1811-1886):

Concert Study No.1 S 145 - Forest Murmures

Berliner Philharmoniker

Radio-Symphonie-Orchester Berlin

Ferenc Fricsay - conductor

CD 3:

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827):

33 Variations on a Waltz of Diabelli in C major op.120

Franz Schubert (177-1828):

Piano Sonata in B flat major D 920

CD 4:

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849):

24 Preludes op.28

Polonaise No.6 in A flat major op.53

Robert Schumann (1810-1856):

Davidsbündler Dances op.6

Fryderyk Chopin (1810-1849):

Etude in E minor op.25 no.5

Mazurka No.4 in A minor op.67

Mazurka No.2 in A minor op.68

CD 5:

Robert Schumann (1810-1856):

Kreisleriana op.16

Fantasia in C major op.17

Symphonic Etudes op.13

Géza Anda - piano

Anda retrospectives continue to prove salutary. Testament has devoted a number of important re-releases to him, and there is fortunately not much duplication between them and this DG boxed set of five discs – Kreisleriana and the later Symphonic Etudes. The kernel of this set is Schumann augmented by Bartók, though not one of the more well-known Anda recordings, and his famed Brahms B flat major Concerto, and a wartime record of which he was greatly proud, the Franck Symphonic Variations. There’s also the not inconsiderable pleasure of listening to him in Chopin, in the Diabelli variations, a Schubert sonata and in some Liszt recorded at various times during his career.

The Brahms is a majestic performance not without some idiosyncrasy. The initial horn statement is certainly personalised – tone, pitch – and the playing of the Berlin Philharmonic under Fricsay is imposing and sometimes almost rhetorical. Some of the brass work is also a little self-regarding but Anda’s passagework is alive to the merest detail, excellently contoured and with great tonal variety not least in the right hand. The left hand makes strong dynamic incursions, and the one or two split notes are of no account given the dynamism of the playing. The deliberate retardation of rhythm in the first movement is notable, as well as the vibrant and convulsive staccato Anda cultivates in the treble. Clarity is paramount in the second movement, not taken too fast, and the slow movement sees constant liveliness of colour and texture, a fusion of the active and the passive, and chamber sensitivity in his responses to Ottmar Borwitzky’s cello solo. The finale is capricious and leisurely – cheeky winds and a relaxed winsomeness.

The Bartók Rhapsody is again with Fricsay in 1960, but this time with the Berlin Radio Symphony. It’s magnificently and generously dramatic, with the piano certainly balanced well (and too) forward. Still there’s blithe wit here, rhythmic tang, Hungarian folk snap and cimbalom imitation.

Turning to his Schumann we are fortunate to have his Kreisleriana from 1966. This is a deft, subtly inflected and very characterful reading. Diminuendi irradiate the opening whilst (2) is elegant yet forward moving. (5) is crystalline and light of texture and the Sehr Langsam (6) gains in cumulative weight and sonority. The Fantasia is a slightly earlier recording, taped in Berlin, and one that possesses a controlled directness of approach and an especially powerful middle movement albeit one that possesses an unusually sensitive contrastive central section. The all-Schumann disc is completed by the 1963 Symphonic Etudes. Fascinating comparisons can be set up between this taping and the wartime recording on 78 also made in Berlin in the Polydor studios. The first recording, made when he was in his very early twenties, is that much more impetuous; speeds are pushed that bit harder, corners turned with a greater sense of youthful zest. That said I prefer the more refined temper of the later traversal – listen to the exquisite left hand voicings in Etude III or the drivingly witty sixth, much less the superiority of his treble sonorities cultivated in Variation V. The finale is delightfully warm even though the youthful Anda was that much more incisive and driving.

The Davidsbündler is another winning example of Anda’s way with the composer. Listen to the real legato delicacy of No.2, the drama and fire of No.4, and the sheer dynamism of No.8. Then again No.13 has splendidly controlled rhythm and bass etching and 14. has a caressing lullaby beauty.

The Concerto with Kubelík has a lyric elasticity that convinces from first to last. The conductor is not one to stint on some heft either which means the first movement goes wonderfully well, the intermezzo has great warmth but no specious lingering and the finale sports some particularly deft orchestral interplay. In later years Anda looked back at his 1943 Amsterdam recording of the Franck Symphonic Variations with unselfconscious admiration, wondering whether he could ever have played as well. With van Beinum an astute collaborator this is certainly an exceptionally rewarding reading – for the sense of an absolutely right weight of touch, for the feeling for direction and for real charm in the Allegretto section. Digitally there seems no hindrance at all.

The Diabelli variations date from a Lucerne session in 1961. As much as the faster variations go so well, Anda explores the slower more intimate ones with sagacity and tonal nuance. He’s alive to the pomposo march of the first variation as much as the sheer dynamism of the fifth or indeed the pawky and earthy humour of the ninth. Nor does he stint the touching lyricism of twenty-nine which he explores with especial sensitivity. There is an example of his Schubert as well – the sonata in B flat major D960, moderate in tempo but plentiful in colour, and also tempo modifications, this is a personalised but in many ways convincing reading (though not everyone will be convinced it has to be said). There’s sufficient tonal amplitude and depth in the slow movement, and it’s not over-emotive, but the scherzo is rather slow in the trio section. The finale is buoyant and graceful.

The Chopin Preludes are winning if not necessarily at the topmost echelon. The fourth is just a touch conventional and lacks the last ounce of feeling. The eighth has great clarity and rhythmic impetus, the fifteenth again a touch sec, the seventeenth sports fine left hand pointing, the twenty-first dynamic shading of a high order and so on. The good very much outweighs the more idiosyncratic. There’s also a genuinely terpsichorean Polonaise (from 1959) with not too much pedal but a strange blip (missed note? bad edit?) along the way. There are three other Chopin pieces from 1943 but with rather high residual shellac noise.

Altogether this is a worthy tribute to Anda. Not only that but it’s valuable in its sweep and in its selection priorities, in its transfer skill and in astutely giving the collector a consolidated collection of real musical value. The poetry and the power can be heard throughout; as much as he was a troubadour he was surely every bit as much the poet. -- Jonathan Woolf

The Brahms is a majestic performance not without some idiosyncrasy. The initial horn statement is certainly personalised – tone, pitch – and the playing of the Berlin Philharmonic under Fricsay is imposing and sometimes almost rhetorical. Some of the brass work is also a little self-regarding but Anda’s passagework is alive to the merest detail, excellently contoured and with great tonal variety not least in the right hand. The left hand makes strong dynamic incursions, and the one or two split notes are of no account given the dynamism of the playing. The deliberate retardation of rhythm in the first movement is notable, as well as the vibrant and convulsive staccato Anda cultivates in the treble. Clarity is paramount in the second movement, not taken too fast, and the slow movement sees constant liveliness of colour and texture, a fusion of the active and the passive, and chamber sensitivity in his responses to Ottmar Borwitzky’s cello solo. The finale is capricious and leisurely – cheeky winds and a relaxed winsomeness.

The Bartók Rhapsody is again with Fricsay in 1960, but this time with the Berlin Radio Symphony. It’s magnificently and generously dramatic, with the piano certainly balanced well (and too) forward. Still there’s blithe wit here, rhythmic tang, Hungarian folk snap and cimbalom imitation.

Turning to his Schumann we are fortunate to have his Kreisleriana from 1966. This is a deft, subtly inflected and very characterful reading. Diminuendi irradiate the opening whilst (2) is elegant yet forward moving. (5) is crystalline and light of texture and the Sehr Langsam (6) gains in cumulative weight and sonority. The Fantasia is a slightly earlier recording, taped in Berlin, and one that possesses a controlled directness of approach and an especially powerful middle movement albeit one that possesses an unusually sensitive contrastive central section. The all-Schumann disc is completed by the 1963 Symphonic Etudes. Fascinating comparisons can be set up between this taping and the wartime recording on 78 also made in Berlin in the Polydor studios. The first recording, made when he was in his very early twenties, is that much more impetuous; speeds are pushed that bit harder, corners turned with a greater sense of youthful zest. That said I prefer the more refined temper of the later traversal – listen to the exquisite left hand voicings in Etude III or the drivingly witty sixth, much less the superiority of his treble sonorities cultivated in Variation V. The finale is delightfully warm even though the youthful Anda was that much more incisive and driving.

The Davidsbündler is another winning example of Anda’s way with the composer. Listen to the real legato delicacy of No.2, the drama and fire of No.4, and the sheer dynamism of No.8. Then again No.13 has splendidly controlled rhythm and bass etching and 14. has a caressing lullaby beauty.

The Concerto with Kubelík has a lyric elasticity that convinces from first to last. The conductor is not one to stint on some heft either which means the first movement goes wonderfully well, the intermezzo has great warmth but no specious lingering and the finale sports some particularly deft orchestral interplay. In later years Anda looked back at his 1943 Amsterdam recording of the Franck Symphonic Variations with unselfconscious admiration, wondering whether he could ever have played as well. With van Beinum an astute collaborator this is certainly an exceptionally rewarding reading – for the sense of an absolutely right weight of touch, for the feeling for direction and for real charm in the Allegretto section. Digitally there seems no hindrance at all.

The Diabelli variations date from a Lucerne session in 1961. As much as the faster variations go so well, Anda explores the slower more intimate ones with sagacity and tonal nuance. He’s alive to the pomposo march of the first variation as much as the sheer dynamism of the fifth or indeed the pawky and earthy humour of the ninth. Nor does he stint the touching lyricism of twenty-nine which he explores with especial sensitivity. There is an example of his Schubert as well – the sonata in B flat major D960, moderate in tempo but plentiful in colour, and also tempo modifications, this is a personalised but in many ways convincing reading (though not everyone will be convinced it has to be said). There’s sufficient tonal amplitude and depth in the slow movement, and it’s not over-emotive, but the scherzo is rather slow in the trio section. The finale is buoyant and graceful.

The Chopin Preludes are winning if not necessarily at the topmost echelon. The fourth is just a touch conventional and lacks the last ounce of feeling. The eighth has great clarity and rhythmic impetus, the fifteenth again a touch sec, the seventeenth sports fine left hand pointing, the twenty-first dynamic shading of a high order and so on. The good very much outweighs the more idiosyncratic. There’s also a genuinely terpsichorean Polonaise (from 1959) with not too much pedal but a strange blip (missed note? bad edit?) along the way. There are three other Chopin pieces from 1943 but with rather high residual shellac noise.

Altogether this is a worthy tribute to Anda. Not only that but it’s valuable in its sweep and in its selection priorities, in its transfer skill and in astutely giving the collector a consolidated collection of real musical value. The poetry and the power can be heard throughout; as much as he was a troubadour he was surely every bit as much the poet. -- Jonathan Woolf

DOWNLOAD FROM ISRA.CLOUD

CD1 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 358.6 MB

CD2 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 370.3 MB

CD3 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 320.1 MB

CD4 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 374.4 MB

CD5 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 337.2 MB

CD1 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 358.6 MB

CD2 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 370.3 MB

CD3 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 320.1 MB

CD4 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 374.4 MB

CD5 Géza Anda Troubadour Of The Piano 05 0105.rar - 337.2 MB

![Casper Tovgaard Christensen & Patrieck Bonnet - Wildflower (2026) [Hi-Res] Casper Tovgaard Christensen & Patrieck Bonnet - Wildflower (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1773374655_dt63w3jqssarr_600.jpg)

![Herbie Mann - Flamingo (1955) [2013 Bethlehem Album Collection 1000] Herbie Mann - Flamingo (1955) [2013 Bethlehem Album Collection 1000]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1773347877_folder.jpg)

![Modha - At Your Pace (2026) [Hi-Res] Modha - At Your Pace (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1773389738_cover.jpg)