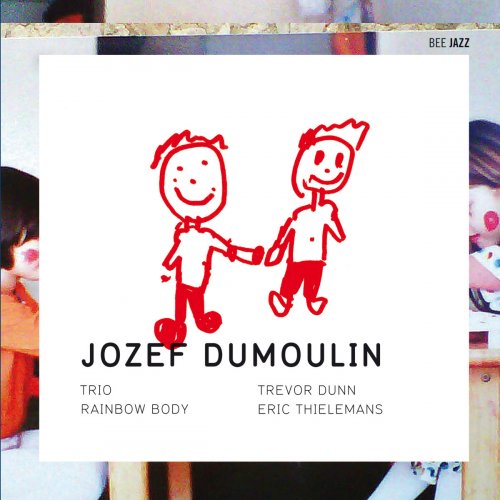

Jozef Dumoulin Trio - Rainbow Body (2011) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Jozef Dumoulin Trio

Title: Rainbow Body

Year Of Release: 2011

Label: BEE JAZZ

Genre: Contemporary Jazz

Quality: FLAC (tracks) 24/44,1

Total Time: 1:04:25

Total Size: 648 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Rainbow Body

Year Of Release: 2011

Label: BEE JAZZ

Genre: Contemporary Jazz

Quality: FLAC (tracks) 24/44,1

Total Time: 1:04:25

Total Size: 648 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Mata (Dumoulin-Dunn-Thielemans) - 4:45

02. For the Monsters Under Our Beds (Dumoulin-Dunn-Thielemans) - 2:01

03. Fuga X (Dumoulin) - 4:38

04. Mei (Dumoulin) - 5:56

05. Shinji (Dumoulin-Dunn-Thielemans) - 3:32

06. The Dragon Warrior (Dumoulin) - 3:53

07. Volkan (Dumoulin) - 8:35

08. Somayeh (Dumoulin) - 0:34

09. Sosuke (Dumoulin) - 3:22

10. Birthday Cake (Dumoulin) - 4:44

11. Sachiko (Dumoulin) - 13:49

12. Venkataraman (Dumoulin-Dunn-Thielemans) - 4:30

13. Asia (aka La Pivellina) (Dumoulin) - 4:06

Belgian pianist Jozef Dumoulin's début release with his band Lidlboj, Trees Are Always Right (Bee Jazz, 2009), revealed this one-time John Taylor student to be something of an aficionado of farting around. This is not meant pejoratively, necessarily; farting around is an honorable activity in some quarters of improvised music, and can give rise to good work (think of Marion Brown's Afternoon of a Georgia Faun (ECM, 1970), for example). That said, the results were encouraging when Dumoulin, as a sideman on reed player Magic Malik's strong Short Cuts (Bee Jazz, 2011), was obliged to keep the farting around in check.

Rainbow Body—essentially an electric-trio record—imposes a further formal discipline on Dumoulin that energizes the proceedings with a focus and coherence missing from Trees.

Rainbow Body's interest and raison d'être derive from its jarring juxtapositions, both in its musical pedigree and in its arrangements and organization. At times Dumoulin solos like an overexcited Chick Corea, but other times his playing more closely resembles Pierre Boulez and the brainy IRCAM crowd. It's jazz in that it's a small group improvising on musical themes, but it also draws upon various generations of electronic and prog-rock sounds and procedures.

In terms of the arrangements, too, there are brash (and sometimes brusque) contrasts. It is rarely the case that all three musicians will pull in different directions, but almost always two are pitted against one: emphatically arrhythmic or atonal (or both) musical materials on one hand, against a conventional and easy-to-grasp framework on the other.

The starkest and probably most successful example is "The Dragon Warrior." Over a cloyingly smooth rhythm track that sounds like a 1980s soft-rock number, solos built from highly-distorted sounds are provided by Dumoulin (certainly) and bassist Trevor Dunn (probably). The contrast is striking, but by the end of the number, the freer- jazz soloists are apparently attempting to hew to the line dictated by the soft-rock number, both in terms of the placement of their rude sound-clusters and in the rising and falling of the notes they play.

On some tracks the keyboards play the straight man, alongside idiosyncratic drumming (as on the subtle "Sosuke," where drummer Eric Thielemans sounds a bit like Paul Motian); on others bassist Dunn anchors the piece (as with " Venkataraman"'s ostinato bass figure). On "Fuga X," (simultaneously an homage to Bach and to Ornette Coleman and Pat Metheny's "Song X," (from Song X (Nonesuch, 1986)?), Dumoulin plays a veritable fugue while the drum and bass turn out a marvelous and entirely straightforward shuffle. The result is not always a success, but the overall effort is always undertaken with intelligence and empathy among the musicians.

The album's overall success and coherence owes a lot to its good sound. Not just Frédéric Carrayol's pristine and full recording, but especially the keyboard sound, upon which Dumoulin lavishes loving attention. Sometimes he sounds like a dated be-beeping 1970s computer, at others he coaxes the chunkiest possible Fender Rhodes sound, with all of its connotations of a diversity of records past.

Rainbow Body—essentially an electric-trio record—imposes a further formal discipline on Dumoulin that energizes the proceedings with a focus and coherence missing from Trees.

Rainbow Body's interest and raison d'être derive from its jarring juxtapositions, both in its musical pedigree and in its arrangements and organization. At times Dumoulin solos like an overexcited Chick Corea, but other times his playing more closely resembles Pierre Boulez and the brainy IRCAM crowd. It's jazz in that it's a small group improvising on musical themes, but it also draws upon various generations of electronic and prog-rock sounds and procedures.

In terms of the arrangements, too, there are brash (and sometimes brusque) contrasts. It is rarely the case that all three musicians will pull in different directions, but almost always two are pitted against one: emphatically arrhythmic or atonal (or both) musical materials on one hand, against a conventional and easy-to-grasp framework on the other.

The starkest and probably most successful example is "The Dragon Warrior." Over a cloyingly smooth rhythm track that sounds like a 1980s soft-rock number, solos built from highly-distorted sounds are provided by Dumoulin (certainly) and bassist Trevor Dunn (probably). The contrast is striking, but by the end of the number, the freer- jazz soloists are apparently attempting to hew to the line dictated by the soft-rock number, both in terms of the placement of their rude sound-clusters and in the rising and falling of the notes they play.

On some tracks the keyboards play the straight man, alongside idiosyncratic drumming (as on the subtle "Sosuke," where drummer Eric Thielemans sounds a bit like Paul Motian); on others bassist Dunn anchors the piece (as with " Venkataraman"'s ostinato bass figure). On "Fuga X," (simultaneously an homage to Bach and to Ornette Coleman and Pat Metheny's "Song X," (from Song X (Nonesuch, 1986)?), Dumoulin plays a veritable fugue while the drum and bass turn out a marvelous and entirely straightforward shuffle. The result is not always a success, but the overall effort is always undertaken with intelligence and empathy among the musicians.

The album's overall success and coherence owes a lot to its good sound. Not just Frédéric Carrayol's pristine and full recording, but especially the keyboard sound, upon which Dumoulin lavishes loving attention. Sometimes he sounds like a dated be-beeping 1970s computer, at others he coaxes the chunkiest possible Fender Rhodes sound, with all of its connotations of a diversity of records past.