Oliver Triendl, Quatuor Sine - Dora Pejačević: Chamber Works (2013)

Artist: Oliver Triendl, Quatuor Sine

Title: Dora Pejačević: Chamber Works

Year Of Release: 2013

Label: CPO

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 90:54

Total Size: 469 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Dora Pejačević: Chamber Works

Year Of Release: 2013

Label: CPO

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 90:54

Total Size: 469 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Dora Pejačević (1885-1923)

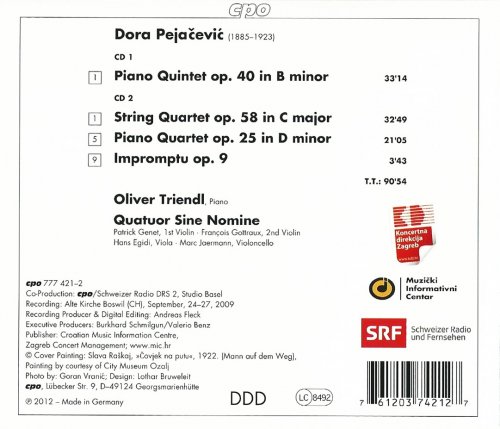

CD 1:

01. Piano Quintet in B minor op.40 - I. Allegro ma non troppo e con energia [0:09:07.23]

02. Piano Quintet in B minor op.40 - II. Poco sostenuto [0:07:50.63]

03. Piano Quintet in B minor op.40 - III. Scherzo. Molto vivace [0:09:02.43]

04. Piano Quintet in B minor op.40 - IV. Allegro moderato [0:07:11.43]

CD 2:

01. String Quartet in C major op.58 - I. Allegro [0:10:42.36]

02. String Quartet in C major op.58 - II. Adagio [0:08:33.28]

03. String Quartet in C major op.58 - III. Minuetto. Allegretto [0:05:37.57]

04. String Quartet in C major op.58 - IV. Rondo. Allegro [0:08:05.39]

05. Piano Quartet in D minor op.25 - I. Allegro ma non tanto [0:07:41.04]

06. Piano Quartet in D minor op.25 - II. Andante con moto [0:04:43.25]

07. Piano Quartet in D minor op.25 - III. Allegretto grazioso [0:04:18.49]

08. Piano Quartet in D minor op.25 - IV. Allegro comodo [0:04:15.01]

09. Impromptu op.9 [0:03:41.37]

Performers:

Oliver Triendl - piano

Quatuor Sine Nomine

It has been just a little over a year-and-a-half since CPO introduced us to Dora Pejacevic (1885–1923), a late-Romantic, Croatian composer, with a recording of her Symphony in F#-Minor (see Fanfare 35:2). That was followed in the very next issue (35:3) by a second CPO release of a Piano Trio and a Cello Sonata by pejacevic. Then, as recently as 36:3, there appeared on the same label a disc of the composer’s songs, reviewed very favorably by Henry Fogel. By now, pejacevic is no longer an unfamiliar name or a novelty, and here, once again from CPO, comes this time a two-disc set adding immeasurably to our knowledge of her chamber music output.

It’s tempting to draw certain parallels between Pejacevic and the French female composer, Louise Farrenc (1804–1875). Though she died 10 years before Pejacevic was born, and wrote music in a style strongly suggestive of Mendelssohn, Farrenc, like pejacevic, was an unusual case among women composers of the period. Both donned the britches reserved for their menfolk—large-scale symphonic, orchestral, and chamber works, and they both proved themselves quite adept at competing with the boys in the same game and on the same playing field.

The B-Minor Piano Quintet occupied Pejacevic from 1915 to 1918. You could say that for its time it’s a fairly conservative work with roots extending well back into the 19th century. But the same could be said of a lot of romantic-styled music still being written into the first and second decades of the 20th century. The quintet is a big work, not only in size—33 minutes—but in boldness of gesture and discourse. Echoes of Brahms ripple through the first movement as Pejacevic revels in the B-Minor-ness of the thing. It’s eruptive and tragic in cast. But occasional flashes of more contemporary lightning illuminate the score.

It’s hard to know exactly what influences Pejacevic was exposed to, but she did receive formal training in Dresden and Munich, and from 1918 on, she traveled extensively in Europe, visiting Vienna, Budapest, and Prague. My guess is that during her studies in Munich around 1907 she would have heard some of the early chamber works by Richard Strauss, particularly his C-Minor Piano Quartet, op. 13. Whether she might also have heard Fauré’s C-Minor Piano Quartet, op. 15, or his D-Minor Piano Quintet, op. 89, it’s impossible to say, but there’s definitely more than a whiff of the French composer’s harmonic and rhythmic fluidity in Pejacevic ’s quintet.

The C-Major String Quartet dates from 1922, and in the time that elapsed between it and completion of the earlier 1918 quintet, musically speaking, Pejacevic has traveled the equivalent of a lightyear or more. Other than the F#-Minor Symphony, which dates from just about the same time as the quintet, it would be really interesting to hear some of the composer’s transitional works that fill in the gap between the quintet and the quartet, for by 1922 Pejacevic ’s style is largely transformed.

Again, it’s really hard to know the composers and music she came into contact with—there’s no mention in the notes about travel to France or a French connection—but this quartet gives off a strong French scent; and I’m not talking about the obvious Debussy and Ravel brands, but rather the almost unmistakable imprint of Vincent d’Indy’s D-Major Quartet, op. 35, of 1890. But another element makes itself felt in Pejacevic ’s quartet as well, and that is the ethno-musical harmonies and rhythms of Croatian folk song and dance, which, at times, sound not all that distantly removed from the Hungarian and Transylvanian sources drawn upon by Bartók.

Setting the calendar back to 1908 and Pejacevic’s earliest chamber work, we come to the Piano Quartet in D Minor, op. 25. Brahms is part sire to this work, but to continue the analogy, it was impregnated more than once, so multiple fathers are responsible for child support. In some of the climactic cadences, the paternity test detects sperm from Tchaikovsky’s A-Minor Piano Trio, as well as from Saint-Saëns’s Bb-Major Piano Quartet, op. 41—strong genetic stock, no doubt, but the question is, did Pejacevic herself know who the daddy was? It’s easy, in retrospect, to say that a given piece of music bears resemblances to this or that written previously by someone else. But in Pejacevic’s case, at least, we can’t really say what she knew or when she knew it.

Her bio tells us that she was essentially a private person, somewhat of a loner, actually, who was uncomfortable in the company of the aristocratic social milieu into which she was born. Many details of her short life are still not known, including the circumstances of her death. One source claims she wrote a suicide note to her husband when she discovered she was with child; another source claims she died giving birth to the child.

Oliver Triendl is one of CPO’s most reliable pianists, but the Sine Nomine Quartet hasn’t been heard from in a long time, at least not by me. My last encounter with these fine Swiss players was in Fanfare 32:3 when I reviewed the ensemble’s release of string quartets by Goldmark. Prior to that, the Sine Nomine Quartet made my 2006 Want List for its recordings of Beethoven’s middle quartets, a set which, sadly, was never followed up with the early and late quartets. Be that as it may, with Triendl and the Sine Nomine Quartet as her advocates, Dora Pejacevic is in the very best of hands.

The more of Pejacevic’s music that becomes known the more it becomes clear that hers was a significant talent and that her contributions to a still viable romantic tradition in the first two decades of the 20th century are well worth hearing. Recommended.

It’s tempting to draw certain parallels between Pejacevic and the French female composer, Louise Farrenc (1804–1875). Though she died 10 years before Pejacevic was born, and wrote music in a style strongly suggestive of Mendelssohn, Farrenc, like pejacevic, was an unusual case among women composers of the period. Both donned the britches reserved for their menfolk—large-scale symphonic, orchestral, and chamber works, and they both proved themselves quite adept at competing with the boys in the same game and on the same playing field.

The B-Minor Piano Quintet occupied Pejacevic from 1915 to 1918. You could say that for its time it’s a fairly conservative work with roots extending well back into the 19th century. But the same could be said of a lot of romantic-styled music still being written into the first and second decades of the 20th century. The quintet is a big work, not only in size—33 minutes—but in boldness of gesture and discourse. Echoes of Brahms ripple through the first movement as Pejacevic revels in the B-Minor-ness of the thing. It’s eruptive and tragic in cast. But occasional flashes of more contemporary lightning illuminate the score.

It’s hard to know exactly what influences Pejacevic was exposed to, but she did receive formal training in Dresden and Munich, and from 1918 on, she traveled extensively in Europe, visiting Vienna, Budapest, and Prague. My guess is that during her studies in Munich around 1907 she would have heard some of the early chamber works by Richard Strauss, particularly his C-Minor Piano Quartet, op. 13. Whether she might also have heard Fauré’s C-Minor Piano Quartet, op. 15, or his D-Minor Piano Quintet, op. 89, it’s impossible to say, but there’s definitely more than a whiff of the French composer’s harmonic and rhythmic fluidity in Pejacevic ’s quintet.

The C-Major String Quartet dates from 1922, and in the time that elapsed between it and completion of the earlier 1918 quintet, musically speaking, Pejacevic has traveled the equivalent of a lightyear or more. Other than the F#-Minor Symphony, which dates from just about the same time as the quintet, it would be really interesting to hear some of the composer’s transitional works that fill in the gap between the quintet and the quartet, for by 1922 Pejacevic ’s style is largely transformed.

Again, it’s really hard to know the composers and music she came into contact with—there’s no mention in the notes about travel to France or a French connection—but this quartet gives off a strong French scent; and I’m not talking about the obvious Debussy and Ravel brands, but rather the almost unmistakable imprint of Vincent d’Indy’s D-Major Quartet, op. 35, of 1890. But another element makes itself felt in Pejacevic ’s quartet as well, and that is the ethno-musical harmonies and rhythms of Croatian folk song and dance, which, at times, sound not all that distantly removed from the Hungarian and Transylvanian sources drawn upon by Bartók.

Setting the calendar back to 1908 and Pejacevic’s earliest chamber work, we come to the Piano Quartet in D Minor, op. 25. Brahms is part sire to this work, but to continue the analogy, it was impregnated more than once, so multiple fathers are responsible for child support. In some of the climactic cadences, the paternity test detects sperm from Tchaikovsky’s A-Minor Piano Trio, as well as from Saint-Saëns’s Bb-Major Piano Quartet, op. 41—strong genetic stock, no doubt, but the question is, did Pejacevic herself know who the daddy was? It’s easy, in retrospect, to say that a given piece of music bears resemblances to this or that written previously by someone else. But in Pejacevic’s case, at least, we can’t really say what she knew or when she knew it.

Her bio tells us that she was essentially a private person, somewhat of a loner, actually, who was uncomfortable in the company of the aristocratic social milieu into which she was born. Many details of her short life are still not known, including the circumstances of her death. One source claims she wrote a suicide note to her husband when she discovered she was with child; another source claims she died giving birth to the child.

Oliver Triendl is one of CPO’s most reliable pianists, but the Sine Nomine Quartet hasn’t been heard from in a long time, at least not by me. My last encounter with these fine Swiss players was in Fanfare 32:3 when I reviewed the ensemble’s release of string quartets by Goldmark. Prior to that, the Sine Nomine Quartet made my 2006 Want List for its recordings of Beethoven’s middle quartets, a set which, sadly, was never followed up with the early and late quartets. Be that as it may, with Triendl and the Sine Nomine Quartet as her advocates, Dora Pejacevic is in the very best of hands.

The more of Pejacevic’s music that becomes known the more it becomes clear that hers was a significant talent and that her contributions to a still viable romantic tradition in the first two decades of the 20th century are well worth hearing. Recommended.

DOWNLOAD FROM ISRA.CLOUD

Oliver Triendl Quatuor Sine Dora Pejačević Chamber Works 13 2305.rar - 469.5 MB

Oliver Triendl Quatuor Sine Dora Pejačević Chamber Works 13 2305.rar - 469.5 MB

![Orchestra of the Upper Atmosphere - Theta Seven (2026) [Hi-Res] Orchestra of the Upper Atmosphere - Theta Seven (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/11/jvowq9y359p2p8nxadl42bkes.jpg)

![Natalie Duncan - Black Moon (2026) [Hi-Res] Natalie Duncan - Black Moon (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1773103343_b23479te9yvqr_600.jpg)