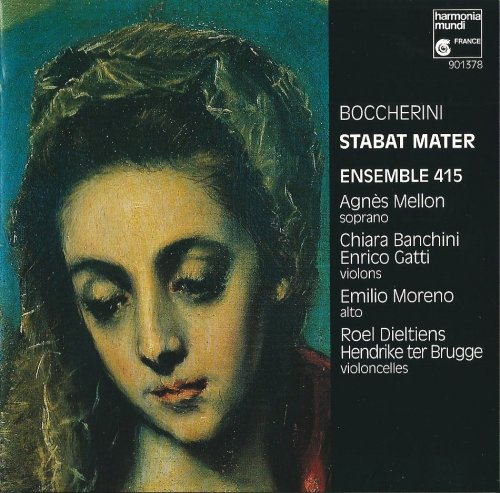

Ensemble 415, Chiara Banchini & Agnes Mellon - Boccherini: Stabat Mater; Symphonies (1992/2001)

Artist: Ensemble 415, Chiara Banchini, Agnes Mellon

Title: Boccherini: Stabat Mater; Symphonies

Year Of Release: 1992 / 2001

Label: Harmonia Mundi

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, artwork)

Total Time: 59:13 min

Total Size: 249 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Boccherini: Stabat Mater; Symphonies

Year Of Release: 1992 / 2001

Label: Harmonia Mundi

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image + .cue, log, artwork)

Total Time: 59:13 min

Total Size: 249 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Stabat Mater, G.532 (1781)

01. Stabat Mater dolorosa: Grave assai

02. Cujus animam gementem: Allegro

03. Quae moerebat et dolebat: Allegretto con motto

04. Quis est homo: Adagio assai

05. Pro peccatis suae gentis: Allegretto

06. Eja mater, fons amoris: Larghetto non tanto

07. Tui nati vulnerati: Allegro vivo

08. Virgo virginum praeclara: Andantino

09. Fac ut portem Christi mortem: Larghetto

10. Fac me plagis vulnerari: Allegro commodo

11. Quando corpus morietur: Andante lento

Quintet in C minor, G.328 (1780)

12. I. Preludio: Adagio

13. II. Allegro vivo

14. III. Adagio

15. IV. Allegro ma non troppo

A quite exceptionally fine disc, which I firmly recommend to anyone with an interest in Boccherini.

Boccherini wrote two versions of his much admired Stabat mater. The original dates from 1781 and is for solo voice; then, 20 years later, he revised it, on a larger scale, using three voices, in order (he said) to avoid the monotony of the single voice and the fatigue to the singer, and also adding a symphony movement to it. This 1801 version was published during his lifetime and in several later editions and seems to have eclipsed the earlier one altogether (which survives only in the autograph manuscript). Yet on hearing this new recording of the original I feel that it conveys the message of the work much more potently than does the more elaborate later version. The fact that it is treated here as an intimate chamber work, with one player to a part, whereas in all others I have heard it is treated as orchestral music, the sources are ambiguous, though quite likely single strings were intended in both versions, is certainly a factor: it comes over much more as a personal expression of contemplation and grief.

This performance, in fact, is of a different order of sensitivity from any other (there are actually four available of the 1801 version). Agnes Mellon has a gentle coolness and a forwardness of tone not unlike Emma Kirkby's, though in certain numbers, for example the "Quae moerebat", where there are real chances to open up the voice in broad melodic spans, she shows a soprano of some amplitude. There is pathos in her singing of the "Quis est homo" and precise and refined detail in the cheerful "Pro peccatis", while in the "Virgo virginum" her floating of the melody, softly accompanied, with pizzicato basses, shows Boccherini at his most exquisitely touching. There is also a fine fugal "Fac me plagis" setting. But the essence of the work belongs in the F minor movements that begin and end it, sombre, deeply felt music of much sensibility. The string playing by Ensemble 415 catches its mood to perfection.

They do well, too, in the String Quintet that serves as a fill-up, a C minor work aptly paired with the Slabat. It starts with a dark-toned Adagio, an extended fugal movement, which (characteristically for Boccherini) recurs after the Allegro, a sturdy yet in a way playful C major piece; lastly there is a C minor Allegro, still quite sombre and pensive. Altogether an unusual work, in a vein not altogether typical of Boccherini's melancholy side and in a way more uncompromising. It makes up a quite exceptionally fine disc, which I firmly recommend to anyone with an interest in Boccherini. -- Gramophone, (September, 1992)

Boccherini wrote two versions of his much admired Stabat mater. The original dates from 1781 and is for solo voice; then, 20 years later, he revised it, on a larger scale, using three voices, in order (he said) to avoid the monotony of the single voice and the fatigue to the singer, and also adding a symphony movement to it. This 1801 version was published during his lifetime and in several later editions and seems to have eclipsed the earlier one altogether (which survives only in the autograph manuscript). Yet on hearing this new recording of the original I feel that it conveys the message of the work much more potently than does the more elaborate later version. The fact that it is treated here as an intimate chamber work, with one player to a part, whereas in all others I have heard it is treated as orchestral music, the sources are ambiguous, though quite likely single strings were intended in both versions, is certainly a factor: it comes over much more as a personal expression of contemplation and grief.

This performance, in fact, is of a different order of sensitivity from any other (there are actually four available of the 1801 version). Agnes Mellon has a gentle coolness and a forwardness of tone not unlike Emma Kirkby's, though in certain numbers, for example the "Quae moerebat", where there are real chances to open up the voice in broad melodic spans, she shows a soprano of some amplitude. There is pathos in her singing of the "Quis est homo" and precise and refined detail in the cheerful "Pro peccatis", while in the "Virgo virginum" her floating of the melody, softly accompanied, with pizzicato basses, shows Boccherini at his most exquisitely touching. There is also a fine fugal "Fac me plagis" setting. But the essence of the work belongs in the F minor movements that begin and end it, sombre, deeply felt music of much sensibility. The string playing by Ensemble 415 catches its mood to perfection.

They do well, too, in the String Quintet that serves as a fill-up, a C minor work aptly paired with the Slabat. It starts with a dark-toned Adagio, an extended fugal movement, which (characteristically for Boccherini) recurs after the Allegro, a sturdy yet in a way playful C major piece; lastly there is a C minor Allegro, still quite sombre and pensive. Altogether an unusual work, in a vein not altogether typical of Boccherini's melancholy side and in a way more uncompromising. It makes up a quite exceptionally fine disc, which I firmly recommend to anyone with an interest in Boccherini. -- Gramophone, (September, 1992)

![Gal Golob - Gal Golob Trio Live at Jazz Cerkno (Live) (2025) [Hi-Res] Gal Golob - Gal Golob Trio Live at Jazz Cerkno (Live) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/09/0sr1cx835g04x8g6nfpgvtips.jpg)

![Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong - The Complete Ella And Louis On Verve [3CD] (1997) Ella Fitzgerald, Louis Armstrong - The Complete Ella And Louis On Verve [3CD] (1997)](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770703124_600.jpg)

![Dela Hüttner’s SwingThing - Pause for a moment (2026) [Hi-Res] Dela Hüttner’s SwingThing - Pause for a moment (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770561049_cover.jpg)