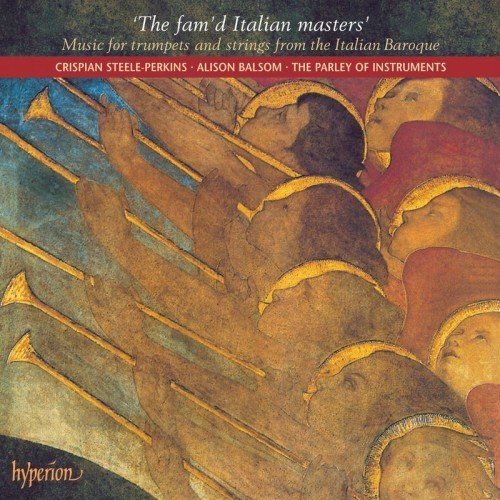

Crispian Steele-Perkins, Alison Balsom - Fam'd Italian Masters: Music for trumpets and strings from the Italian Baroque (2003)

Artist: Crispian Steele-Perkins, Alison Balsom

Title: Fam'd Italian Masters: Music for trumpets and strings from the Italian Baroque

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical / trumpets and strings

Quality: APE (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 62'28

Total Size: 283 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Fam'd Italian Masters: Music for trumpets and strings from the Italian Baroque

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: Hyperion

Genre: Classical / trumpets and strings

Quality: APE (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 62'28

Total Size: 283 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Sonata a 6 in D major Ferdinando Lazzari (1678-1754)

1 Movement 1: Presto e spicco [1:58]

2 Movement 2: Grave [0:35]

3 Movement 3: Canzona [0:59]

4 Movement 4: Grave [0:31]

5 Movement 5: Presto [1:40]

6 Sonata a 4 in G minor 'La sampiera' [3:36] Maurizio Cazzati (1620-1677)

Sonata a 5 in D major, Op 3 No 10 Andrea Grossi (fl1680-1690)

7 Movement 1: Vivace [1:11]

8 Movement 2: Adagio [2:06]

9 Movement 3: Grave [0:59]

10 Movement 4: Presto [1:13]

Sonata a 5 in D major Giuseppe Maria Jacchini (c1663-1727)

11 Movement 1: Grave – Allegro [1:08]

12 Movement 2: Grave [0:38]

13 Movement 3: Allegro [1:06]

14 Movement 4: Grave – Allegro [1:16]

15 Sonata in A minor 'La sassatelli', Op 5 No 10 [3:06] Giovanni Vitali (1632-1692)

Sonata a 5 in C major Alessandro Melani (1639-1703)

16 Movement 1: Adagio – Allegro [2:01]

17 Movement 2: Allegro [3:14]

18 Movement 3: Canzona – Grave [2:42]

19 Movement 4: Vivace [2:22]

20 Sonata in E minor, Op 10 No 17 [5:15] Giovanni Legrenzi (1626-1690)

Il barcheggio Alessandro Stradella (1639-1682)

21 Sinfonia in D major. Movement 1: [Allegro] [0:56]

22 Sinfonia in D major. Movement 2: Andante [2:13]

23 Sinfonia in D major. Movement 3: Allegro ma non troppo [1:16]

24 Sinfonia in D major. Movement 4: Allegro [1:36]

Sonata a 5 in D major, G7 Giuseppe Torelli (1658-1709)

25 Movement 1: Grave – Allegro [1:02]

26 Movement 2: Adagio [1:26]

27 Movement 3: Allegro [1:11]

28 Movement 4: Grave – Allegro [1:44]

Sonata a 4 No 1 in F minor Alessandro Scarlatti (1660-1725)

29 Movement 1: Grave [0:51]

30 Movement 2: Allegro [1:38]

31 Movement 3: Larghetto [2:09]

32 Movement 4: Allemanda [1:08]

Concerto in C major, RV537 Antonio Vivaldi (1678-1741)

33 Movement 1: Vivace [2:52]

34 Movement 2: Largo [0:33]

35 Movement 3: Allegro [3:16]

Until the middle of the seventeenth century, the trumpet was essentially a ceremonial instrument, played by soldiers and courtly attendants rather than musicians; it was normally used in trumpet-and-drum bands, in which fanfares and popular tunes were clothed in improvised drone accompaniments. However, German composers such as Michael Praetorius and Heinrich Schütz began to experiment with using trumpets in composed art music around 1620, and soon after 1650 composers began to write concerted sonatas for one or two trumpets with strings and continuo—the repertory that is explored in this disc.

It is normally thought that the first trumpet sonatas were written in Bologna. The earliest printed trumpet sonatas were certainly published in 1665 by Maurizio Cazzati, maestro di capella at San Petronio in Bologna between 1657 and 1671, and the archives at San Petronio contain a large repertory of sonatas, sinfonias and concertos with trumpets, some of which are included on this CD. However, there are trumpet sonatas surviving in manuscripts in northern European libraries that may be just as early or even earlier. A case in point is the sonata by the Roman composer and singer Alessandro Melani. It is found in manuscript at Uppsala in Sweden, probably copied in the 1680s or ’90s though a shorter version for a single trumpet in an Oxford manuscript may go back to the middle of the century. The piece is in an early style and is in C major rather than D major, the standard key for later Italian trumpet music. The piece is also unusual in that the violin parts are in scordatura (using violins tuned b-e'-b'-e'' instead of g-d'-a'-e''). It is not clear whether that was part of Melani’s original conception, though it certainly creates an unusual and attractive sonority.

Alessandro Stradella was another important early composer of trumpet music. Like Melani, he worked in Rome for much of his career, though by 1681, when he wrote the wedding cantata Il barcheggio, he was living in Genoa; he was murdered in a Genoese street the following February and Il barcheggio is said to have been his last work. Its self-contained sinfonia sounds remarkably modern, partly because it uses a bright scoring with three equal treble parts, and partly because it has a clear four-movement structure, with logical harmonic patterns.

Another early trumpet work is the sonata by Andrea Grossi, published in his Op 3 of 1682. It has a some archaic features—for instance, the trumpet tends to alternate rather than combine with the upper strings—though the central adagio, featuring the trumpet in an expressive rather than virtuosic role, is unusual for the time. Little is known about Grossi, though he is known to have been a violinist in the service of the Duke of Mantua around 1680.

The three trumpet works in this programme by Bologna composers offer a sample of forms and styles around 1700. The sonata by Giuseppe Maria Jacchini has the same three-treble scoring as the Stradella sinfonia, though it is more old-fashioned in its structure and musical language: it is relatively short-winded and is a patchwork of six short, contrasted sections. Jacchini was a cellist in the musical establishment at San Petronio from 1680 until his death in 1727, and may have been partly responsible for developing the cello as a solo instrument in concerted sonatas; in the present sonata the central trumpet solo has a soloistic bass part that is clearly intended for his instrument.

In the sonatas by Lazzari and Torelli the cello is given a proper solo accompanied by a separate continuo part; in the Lazzari it has an expressive duet with the first violin, while in the Torelli it has a duet with the trumpet. Both works illustrate the trend around 1700 to more virtuosic and idiomatic writing, and for longer, more logically organized separate movements instead of the old ‘patchwork’ structures. Lazzari was a Franciscan monk who worked in his native Bologna throughout his life, with the exception of two periods spent in Venice. Torelli was also a native of Bologna and worked there until 1696, though he spent most of his later career in Germany.

We do not know where and when Vivaldi wrote his well-known concerto, his only work for trumpets and strings. It is similar in idiom to some Bologna works, though it is in C major rather than D major—a distinctive feature found in other works by Vivaldi with trumpet.

As a contrast to the major-key and generally lively trumpet works, we have included some contemporary examples of four-part string sonatas. The sonata à quattro was less popular at the time than the ubiquitous trio sonata, and is rather neglected today, though it contains a wealth of fine music with a preponderance of introspective, minor-key works—as this CD demonstrates. It is also of interest in that the genre is the true ancestor of the Classical string quartet. The sonatas by Cazzati and Vitali are typical examples of Bolognese four-part sonatas: they are relatively brief, are full of dense counterpoint and have chromatic sections. Vitali was born in Bologna and studied with Cazzati, though he spent most of his career at the Modenese court.

The sonatas by Legrenzi and Scarlatti are also densely contrapuntal, though they are quite different in style. Legrenzi was working in Venice in 1673, when he published his Op 10, and dedicated the collection to the Austrian emperor Leopold I, which is presumably why it includes two sonatas for four viols and continuo. Viols were largely obsolete in Italy at the time, but were still cultivated a good deal in Austria. This is probably why the sonata recorded here was printed in a double-clef format, allowing it to be played in C minor on viols and in E minor by a string quartet. In the work Legrenzi achieves a remarkable synthesis between the contrapuntal idiom of the Renaissance and the chromatic harmony of his own time. We do not know anything about the origins of Alessandro Scarlatti’s work, except that it is found in manuscripts in Paris and Münster as a sonata for string quartet ‘senza cembalo’, but as a concerto with continuo and additional ripieno string parts as the first of a set of Six Concertos published in London around 1740. It is likely, however, that the concerto version is not Scarlatti’s work, and was cobbled together in eighteenth-century England; the additional parts certainly do not add anything to the original.

Two features of this recording are worthy of comment. First, all the works are played one to a part. There is no doubt that the sonata à quattro was essentially thought of as chamber music rather than orchestral music around 1700, even though the genre was often used in church. Furthermore, Richard Maunder has recently argued that the concerto was normally a one-to-a-part genre during the Baroque period; the vast majority of all Baroque concertos survive only in single sets of parts, even in places such as San Petronio in Bologna, where other genres were performed with large forces. Second, it has become fashionable in recent years to use large continuo groups of plucked instruments in all sort of Baroque music. However, the printed and manuscript sources of the repertory recorded here normally only have a single continuo part, most commonly labelled ‘organo’. For this reason we have used a fine Italian-style organ by Goetze and Gwynn for this recording. It is typical of the single-manual instruments used in Italian Baroque churches, and is much more powerful than the small portable chest instruments usually heard in modern performances and recordings.

It is normally thought that the first trumpet sonatas were written in Bologna. The earliest printed trumpet sonatas were certainly published in 1665 by Maurizio Cazzati, maestro di capella at San Petronio in Bologna between 1657 and 1671, and the archives at San Petronio contain a large repertory of sonatas, sinfonias and concertos with trumpets, some of which are included on this CD. However, there are trumpet sonatas surviving in manuscripts in northern European libraries that may be just as early or even earlier. A case in point is the sonata by the Roman composer and singer Alessandro Melani. It is found in manuscript at Uppsala in Sweden, probably copied in the 1680s or ’90s though a shorter version for a single trumpet in an Oxford manuscript may go back to the middle of the century. The piece is in an early style and is in C major rather than D major, the standard key for later Italian trumpet music. The piece is also unusual in that the violin parts are in scordatura (using violins tuned b-e'-b'-e'' instead of g-d'-a'-e''). It is not clear whether that was part of Melani’s original conception, though it certainly creates an unusual and attractive sonority.

Alessandro Stradella was another important early composer of trumpet music. Like Melani, he worked in Rome for much of his career, though by 1681, when he wrote the wedding cantata Il barcheggio, he was living in Genoa; he was murdered in a Genoese street the following February and Il barcheggio is said to have been his last work. Its self-contained sinfonia sounds remarkably modern, partly because it uses a bright scoring with three equal treble parts, and partly because it has a clear four-movement structure, with logical harmonic patterns.

Another early trumpet work is the sonata by Andrea Grossi, published in his Op 3 of 1682. It has a some archaic features—for instance, the trumpet tends to alternate rather than combine with the upper strings—though the central adagio, featuring the trumpet in an expressive rather than virtuosic role, is unusual for the time. Little is known about Grossi, though he is known to have been a violinist in the service of the Duke of Mantua around 1680.

The three trumpet works in this programme by Bologna composers offer a sample of forms and styles around 1700. The sonata by Giuseppe Maria Jacchini has the same three-treble scoring as the Stradella sinfonia, though it is more old-fashioned in its structure and musical language: it is relatively short-winded and is a patchwork of six short, contrasted sections. Jacchini was a cellist in the musical establishment at San Petronio from 1680 until his death in 1727, and may have been partly responsible for developing the cello as a solo instrument in concerted sonatas; in the present sonata the central trumpet solo has a soloistic bass part that is clearly intended for his instrument.

In the sonatas by Lazzari and Torelli the cello is given a proper solo accompanied by a separate continuo part; in the Lazzari it has an expressive duet with the first violin, while in the Torelli it has a duet with the trumpet. Both works illustrate the trend around 1700 to more virtuosic and idiomatic writing, and for longer, more logically organized separate movements instead of the old ‘patchwork’ structures. Lazzari was a Franciscan monk who worked in his native Bologna throughout his life, with the exception of two periods spent in Venice. Torelli was also a native of Bologna and worked there until 1696, though he spent most of his later career in Germany.

We do not know where and when Vivaldi wrote his well-known concerto, his only work for trumpets and strings. It is similar in idiom to some Bologna works, though it is in C major rather than D major—a distinctive feature found in other works by Vivaldi with trumpet.

As a contrast to the major-key and generally lively trumpet works, we have included some contemporary examples of four-part string sonatas. The sonata à quattro was less popular at the time than the ubiquitous trio sonata, and is rather neglected today, though it contains a wealth of fine music with a preponderance of introspective, minor-key works—as this CD demonstrates. It is also of interest in that the genre is the true ancestor of the Classical string quartet. The sonatas by Cazzati and Vitali are typical examples of Bolognese four-part sonatas: they are relatively brief, are full of dense counterpoint and have chromatic sections. Vitali was born in Bologna and studied with Cazzati, though he spent most of his career at the Modenese court.

The sonatas by Legrenzi and Scarlatti are also densely contrapuntal, though they are quite different in style. Legrenzi was working in Venice in 1673, when he published his Op 10, and dedicated the collection to the Austrian emperor Leopold I, which is presumably why it includes two sonatas for four viols and continuo. Viols were largely obsolete in Italy at the time, but were still cultivated a good deal in Austria. This is probably why the sonata recorded here was printed in a double-clef format, allowing it to be played in C minor on viols and in E minor by a string quartet. In the work Legrenzi achieves a remarkable synthesis between the contrapuntal idiom of the Renaissance and the chromatic harmony of his own time. We do not know anything about the origins of Alessandro Scarlatti’s work, except that it is found in manuscripts in Paris and Münster as a sonata for string quartet ‘senza cembalo’, but as a concerto with continuo and additional ripieno string parts as the first of a set of Six Concertos published in London around 1740. It is likely, however, that the concerto version is not Scarlatti’s work, and was cobbled together in eighteenth-century England; the additional parts certainly do not add anything to the original.

Two features of this recording are worthy of comment. First, all the works are played one to a part. There is no doubt that the sonata à quattro was essentially thought of as chamber music rather than orchestral music around 1700, even though the genre was often used in church. Furthermore, Richard Maunder has recently argued that the concerto was normally a one-to-a-part genre during the Baroque period; the vast majority of all Baroque concertos survive only in single sets of parts, even in places such as San Petronio in Bologna, where other genres were performed with large forces. Second, it has become fashionable in recent years to use large continuo groups of plucked instruments in all sort of Baroque music. However, the printed and manuscript sources of the repertory recorded here normally only have a single continuo part, most commonly labelled ‘organo’. For this reason we have used a fine Italian-style organ by Goetze and Gwynn for this recording. It is typical of the single-manual instruments used in Italian Baroque churches, and is much more powerful than the small portable chest instruments usually heard in modern performances and recordings.

![Larry Nocella - Everything Happens To Me (Remastered) (2026) [Hi-Res] Larry Nocella - Everything Happens To Me (Remastered) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770910166_cover.jpg)

![Tomeka Reid - dance! skip! hop! (2026) [Hi-Res] Tomeka Reid - dance! skip! hop! (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770830819_v46zfbrujdggb_600.jpg)