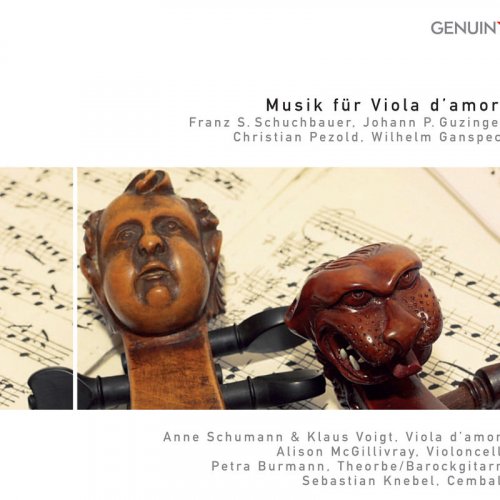

Klaus Voigt - Music for Viola d'amore (2010)

Artist: Klaus Voigt

Title: Music for Viola d'amore

Year Of Release: 2010

Label: Genuin

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks+booklet)

Total Time: 76:27 min

Total Size: 436 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Title: Music for Viola d'amore

Year Of Release: 2010

Label: Genuin

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks+booklet)

Total Time: 76:27 min

Total Size: 436 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. I. Preludio: Allegro

02. II. Adagio

03. III. Allegro

04. IV. Aria

05. V. Giga: Allegro

06. I. Fantasia: Andante

07. II. Rigadon I-II

08. III. Menuet

09. IV. Gigue

10. I. Allegro

11. II. Gavotte

12. III. Menuett

13. I. Sonata: Adagio

14. II. Allegro

15. III. Musette

16. IV. Aria inglese

17. IV. Rondeaux

18. VI. Gigue: Allegro

19. I. Intrada

20. II. Allemande

21. III. Courante

22. IV. Saraband

23. V. Menuet

24. VI. Gigue

25. VII. Aria

26. VIII. Gavotte

27. IX. Bouree

28. X. Rondeau

29. XI. Menuet

30. I. Overture (Passepied)

31. II. Gavotte

32. III. Menuet

33. IV. Bouree

34. V. Hornepipe

35. VI. Gigue

36. VII. Chaccone

Even to the knowledgeable readers of this journal, I’d venture that the history of music in Germany up to the time of Bach is largely a blank slate. A few of Bach’s predecessors, such as Schütz, Schein, Scheidt, Froberger, Böhm, and Buxtehude, may come to mind; but for many Bach still represents the beginning and the end of the German Baroque. In large part, I think this is due to the fact that from the very start of the 17th century it was Italy where innovation in opera and concerted instrumental music flowered, while Germany lagged somewhat behind. Generally, we are more familiar with developments in Italy during this time—say from Monteverdi through Corelli—than we are with the parallel developments in Germany. One of the genuine surprises this disc holds in store for us is that all of the music it contains is by composers not prior to Bach but his almost exact contemporaries, yet their names are figuratively as well as literally (see the headnote) anonymous.

With the exception of the suite by Johann Peter Guzinger (1683–1773), all of the pieces on the disc are found in the collection of music assembled by the Dresden court concertmaster Johann Georg Pisendel (1687–1755), a student of Torelli and one of the most famous German violin and viola d’amore virtuosos of his day. Not all of the composers named in the headnote, however, were attached to the Dresden court orchestra or direct associates of Pisendel. Wilhelm Ganspeck (1687–1770), son of Munich court musician Johann Kaspar Ganspeck, appears in the records of the Ranshoven convent as a composer of sacred works, while Franz Simon Schuchbauer (d. 1743) is noted as a member of the Elector’s orchestra in Munich. Christian Pezold (1677–1733), on the other hand, led two lives. He was organist at Dresden’s Sophienkirche and also an official court composer who traveled with Pisendel and the orchestra to Venice. Guzinger, whose suite is not part of Pisendel’s collection, was employed as a chamber musician and known as a player of the “grand viole d’amour” at the Bavarian court of the Bishop of Eichstätt.

All of these works have two things in common: (1) Stylistically, they are influenced by earlier Italian composers, particularly Corelli and Torelli, whose music was rapidly spreading to Germany and throughout the Continent; and (2) Formally, they fall into the dance suite category with an as yet unfixed number and order of movements.

Defining the physical properties of the viola d’amore and detailing its characteristics are best left to Genuin’s informative booklet note authored by Manfred Fechner. The gist of it is that we are not dealing with a single instrument but with one that comes in a variety of configurations and tunings, and has a chameleon-like ability to change its tonal colorations. Simply put, it’s an instrument whose primary set of strings, most commonly six or seven, are underlain by a secondary set of corresponding sympathetic strings, usually tuned to the same pitches as the playing strings, which then vibrate in resonance with the primary string set, producing a kind of silvery, glistening sound. However, the number and type of strings employed, in combination with various tuning options, makes for a mathematically enormous number of possibilities. In the anonymous D-Major Trio, for example, we hear two violas d’amore fitted with metal strings made, respectively, of iron, brass, and iron with copper winding.

Unlike other 17th- and early 18th-century instruments that either became obsolete or evolved into their modern-day counterparts, the viola d’amore survived pretty much unchanged up to the present by going into a period of temporary hibernation. But for a few notable exceptions—Albrechtsberger, Hoffmeister, the Stamitzes father and son, and a small number of others—composers lost interest in the instrument during the latter half of the 18th century. Interest was rekindled in the 19th century with the famous viola d’amore solo by Meyerbeer in Les Huguenots , and then by similar solos in operas by Massenet, Erkel, and Puccini. The trend continued into the 20th century with more than just isolated opera interludes—Charpentier’s Louise (1900), Massenet’s Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame (1902), and Pfitzner’s Palestrina (1917). Now it became the featured solo or obbligato instrument in a number of extended orchestral works—Loeffler’s La Mort de Tintagiles for viola d’amore and orchestra, Hindemith’s Sonata for Viola d’amore and Piano and Kammermusik No. 6, and too many others to begin to name.

The soloists constituting the current ensemble are an eclectic mix. Anne Schumann, a former member of the Leipzig Gewnadhaus Orchestra, and Klaus Voigt, cofounder of the Telemannisches Collegium Michaelstein, are of German background and training. Allison McGillivray is a native Scot who studied in Glasgow and has performed with the English Concert and the Academy of Ancient Music. Currently, she is a professor on the faculty of London’s Guildhall School. Petra Burmann studied guitar in Magdeburg, but came to the U.S. to study historical lute instruments with Nigel North at the Early Music Institute at Indiana University. She currently resides in Halle/Saale, where she chairs the guitar department at the George Frederick Handel Conservatory. Sebastian Knebel, as a resident of Dresden, is closest geographically to the music on this CD. He is a distinguished harpsichordist and organist who has devoted himself to the preservation of historic organs in addition to managing a full calendar as a widely in-demand performing artist.

Those with an interest in and taste for German Baroque music under the sway of Italian influences will find much to enjoy in this release. Though all of these works date from approximately the same time as Telemann and Bach, they are not as advanced or sophisticated in their writing as is that of either the more cosmopolitan Hamburg master or the great Leipzig cantor. Rather, similarities abound with the music of Johann David Heinichen (1683–1729), who was also active in Dresden around the same time.

Performances and recording are wonderful. Strongly recommended for opening ears to obscure composers and music that have been eclipsed by more famous names of the period, just as have later 18th- and 19th-century composers and music been eclipsed by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. This one gets a gold star.

With the exception of the suite by Johann Peter Guzinger (1683–1773), all of the pieces on the disc are found in the collection of music assembled by the Dresden court concertmaster Johann Georg Pisendel (1687–1755), a student of Torelli and one of the most famous German violin and viola d’amore virtuosos of his day. Not all of the composers named in the headnote, however, were attached to the Dresden court orchestra or direct associates of Pisendel. Wilhelm Ganspeck (1687–1770), son of Munich court musician Johann Kaspar Ganspeck, appears in the records of the Ranshoven convent as a composer of sacred works, while Franz Simon Schuchbauer (d. 1743) is noted as a member of the Elector’s orchestra in Munich. Christian Pezold (1677–1733), on the other hand, led two lives. He was organist at Dresden’s Sophienkirche and also an official court composer who traveled with Pisendel and the orchestra to Venice. Guzinger, whose suite is not part of Pisendel’s collection, was employed as a chamber musician and known as a player of the “grand viole d’amour” at the Bavarian court of the Bishop of Eichstätt.

All of these works have two things in common: (1) Stylistically, they are influenced by earlier Italian composers, particularly Corelli and Torelli, whose music was rapidly spreading to Germany and throughout the Continent; and (2) Formally, they fall into the dance suite category with an as yet unfixed number and order of movements.

Defining the physical properties of the viola d’amore and detailing its characteristics are best left to Genuin’s informative booklet note authored by Manfred Fechner. The gist of it is that we are not dealing with a single instrument but with one that comes in a variety of configurations and tunings, and has a chameleon-like ability to change its tonal colorations. Simply put, it’s an instrument whose primary set of strings, most commonly six or seven, are underlain by a secondary set of corresponding sympathetic strings, usually tuned to the same pitches as the playing strings, which then vibrate in resonance with the primary string set, producing a kind of silvery, glistening sound. However, the number and type of strings employed, in combination with various tuning options, makes for a mathematically enormous number of possibilities. In the anonymous D-Major Trio, for example, we hear two violas d’amore fitted with metal strings made, respectively, of iron, brass, and iron with copper winding.

Unlike other 17th- and early 18th-century instruments that either became obsolete or evolved into their modern-day counterparts, the viola d’amore survived pretty much unchanged up to the present by going into a period of temporary hibernation. But for a few notable exceptions—Albrechtsberger, Hoffmeister, the Stamitzes father and son, and a small number of others—composers lost interest in the instrument during the latter half of the 18th century. Interest was rekindled in the 19th century with the famous viola d’amore solo by Meyerbeer in Les Huguenots , and then by similar solos in operas by Massenet, Erkel, and Puccini. The trend continued into the 20th century with more than just isolated opera interludes—Charpentier’s Louise (1900), Massenet’s Le Jongleur de Notre-Dame (1902), and Pfitzner’s Palestrina (1917). Now it became the featured solo or obbligato instrument in a number of extended orchestral works—Loeffler’s La Mort de Tintagiles for viola d’amore and orchestra, Hindemith’s Sonata for Viola d’amore and Piano and Kammermusik No. 6, and too many others to begin to name.

The soloists constituting the current ensemble are an eclectic mix. Anne Schumann, a former member of the Leipzig Gewnadhaus Orchestra, and Klaus Voigt, cofounder of the Telemannisches Collegium Michaelstein, are of German background and training. Allison McGillivray is a native Scot who studied in Glasgow and has performed with the English Concert and the Academy of Ancient Music. Currently, she is a professor on the faculty of London’s Guildhall School. Petra Burmann studied guitar in Magdeburg, but came to the U.S. to study historical lute instruments with Nigel North at the Early Music Institute at Indiana University. She currently resides in Halle/Saale, where she chairs the guitar department at the George Frederick Handel Conservatory. Sebastian Knebel, as a resident of Dresden, is closest geographically to the music on this CD. He is a distinguished harpsichordist and organist who has devoted himself to the preservation of historic organs in addition to managing a full calendar as a widely in-demand performing artist.

Those with an interest in and taste for German Baroque music under the sway of Italian influences will find much to enjoy in this release. Though all of these works date from approximately the same time as Telemann and Bach, they are not as advanced or sophisticated in their writing as is that of either the more cosmopolitan Hamburg master or the great Leipzig cantor. Rather, similarities abound with the music of Johann David Heinichen (1683–1729), who was also active in Dresden around the same time.

Performances and recording are wonderful. Strongly recommended for opening ears to obscure composers and music that have been eclipsed by more famous names of the period, just as have later 18th- and 19th-century composers and music been eclipsed by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. This one gets a gold star.

![Eck Adahg Jeff Armstrong & Ra Kalam Bob Moses - Freedom is Now (2026) [Hi-Res] Eck Adahg Jeff Armstrong & Ra Kalam Bob Moses - Freedom is Now (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1767358838_qkuy7nuk29ov3_600.jpg)

![Manny Albam and His Jazz Greats - Play Music from West Side Story (Remastered Edition) (2025) [Hi-Res] Manny Albam and His Jazz Greats - Play Music from West Side Story (Remastered Edition) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1767257208_maws500.jpg)