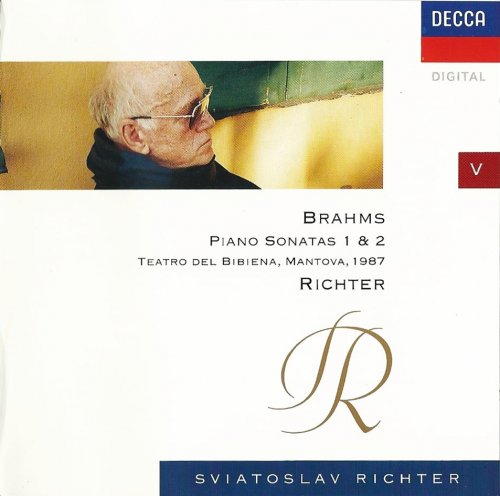

Sviatoslav Richter - Brahms: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 & 2 (1993)

Artist: Sviatoslav Richter

Title: Brahms: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 & 2

Year Of Release: 1993

Label: Decca

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 58:55

Total Size: 206 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Brahms: Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 & 2

Year Of Release: 1993

Label: Decca

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 58:55

Total Size: 206 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

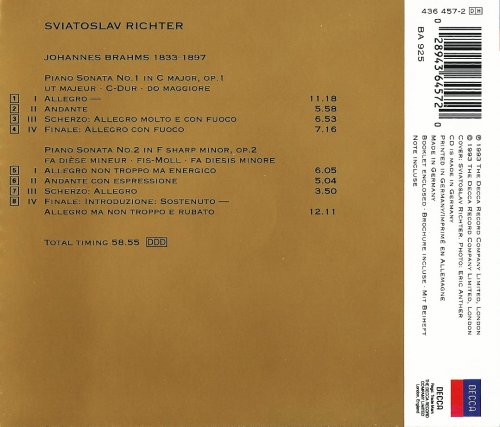

01. Piano Sonata No. 1 in C major, Op. 1: I. Allegro [0:11:20.00]

02. Piano Sonata No. 1 in C major, Op. 1: II. Andante [0:05:57.70]

03. Piano Sonata No. 1 in C major, Op. 1: III. Scherzo: Allegro molto e con fuoco [0:06:54.55]

04. Piano Sonata No. 1 in C major, Op. 1: IV. Finale: Allegro con fuoco [0:07:23.37]

05. Piano Sonata No. 2 in F-sharp minor, Op. 2: I. Allegro non troppo ma energico [0:06:10.38]

06. Piano Sonata No. 2 in F-sharp minor, Op. 2: II. Andante con espressione [0:05:03.67]

07. Piano Sonata No. 2 in F-sharp minor, Op. 2: III. Scherzo: Allegro [0:03:53.58]

08. Piano Sonata No. 2 in F-sharp minor, Op. 2: IV. Finale: Introduzione: Sostenuto - Allegro ma non troppo e rubato [0:12:11.12]

Performers:

Sviatoslav Richter - piano

When assessing any performance by Richter it's a good idea to try, so far as the thing is possible, to forget who is playing. The man has been subjected to so much undiscriminating and copycat adulation that the things that make him genuinely special are easily obscured. In fact these two performances of the early Brahms sonatas are completely without idiosyncrasies. They are live performances, by a top-flight virtuoso and general legend then in his eighth decade, that seem to me to come close to the classic performances from Katchen, now I believe available only as part of his omnibus Brahms edition.

Richter's speeds, with one exception, are a little slower than Katchen's. However the real difference is that the feeling of youthfulness from Katchen is not to be heard from a man of 70-odd. Technically there is very little to choose. Richter doesn't quite equal Katchen in the trills and filigree right-hand work in the early part of the finale of the F# minor, but that is the only significant difference in the technical respect. In other respects where Richter differs from Katchen this is obviously by his choice. I'm inclined to go along with that choice in the first movement of the C major, the very first track on the disc. Here Richter's steadier tempo helps in keeping the outlines of the movement clear for a listener whose wits are not as quick as Katchen's are. Again, in the sets of variations that comprise the slow movements of both sonatas, many will doubtless prefer Richter's more introverted manner. For me, there's not much to choose between them in the op 1 set, but I miss from Richter the highlighted tonal contrasts that Katchen brings to the corresponding set in op 2.

As for the rest, it's basically Katchen all the way for me. Richter's accounts do not present any greatly different outlook on the two sonatas, and they are first-class in their own right. For me the overriding consideration is that these sonatas are the stupefyingly great works of a composer barely 20. His maturity, scholarship, technical command, self-assurance and sense of his own destiny at such an age are maybe without parallel or equal in all the 19th century. At the same time he was an exuberant youngster, and where Katchen, taken from us in his prime, scores for me is in his exuberant youthfulness. The matter defines itself most clearly in the scherzo and in the last movement of op 1, respectively `allegro molto' and `allegro con brio'. It's pretty obvious to me which performance more epitomises those instructions, top-class though both are.

One interesting thing I think I have discovered from the liner-note here is the origin of a recurrent theme in the writings of Richter's supporters' club. Richter is often said to possess and exhibit a capacity for exceptional `unity', or some equivalent expression, in his accounts. This will seem highly questionable to any listener for whom the sense of unity in a work of music is a matter for the composer in all ways that count, not for the interpreter. The concept seems to date back to Richter's understandably enthusiastic teacher Neuhaus. What I believe the expression meant from Neuhaus was that when Richter offered a novel interpretation he could sustain the novelty in a coherent way. What I believe the expression means from those who have subsequently recycled it is precisely nothing. There is any amount of true gold to be found in the work of this colossus of the 20th century piano, but we need to be prepared to think about it and exercise our critical faculties and not to find mares' nests and repeat meaningless formulae. Richter has left us very little Brahms, and I am only too grateful for what I have here. These are probably not pieces that give scope for the kind of insights that make Richter one of the ultimate greats, and if they don't give scope for that we should not pretend to be finding it. This is another major memorial to a unique artist, unique not least in his unpredictability. Where he has surprised me this time is in being so mainstream.

Richter's speeds, with one exception, are a little slower than Katchen's. However the real difference is that the feeling of youthfulness from Katchen is not to be heard from a man of 70-odd. Technically there is very little to choose. Richter doesn't quite equal Katchen in the trills and filigree right-hand work in the early part of the finale of the F# minor, but that is the only significant difference in the technical respect. In other respects where Richter differs from Katchen this is obviously by his choice. I'm inclined to go along with that choice in the first movement of the C major, the very first track on the disc. Here Richter's steadier tempo helps in keeping the outlines of the movement clear for a listener whose wits are not as quick as Katchen's are. Again, in the sets of variations that comprise the slow movements of both sonatas, many will doubtless prefer Richter's more introverted manner. For me, there's not much to choose between them in the op 1 set, but I miss from Richter the highlighted tonal contrasts that Katchen brings to the corresponding set in op 2.

As for the rest, it's basically Katchen all the way for me. Richter's accounts do not present any greatly different outlook on the two sonatas, and they are first-class in their own right. For me the overriding consideration is that these sonatas are the stupefyingly great works of a composer barely 20. His maturity, scholarship, technical command, self-assurance and sense of his own destiny at such an age are maybe without parallel or equal in all the 19th century. At the same time he was an exuberant youngster, and where Katchen, taken from us in his prime, scores for me is in his exuberant youthfulness. The matter defines itself most clearly in the scherzo and in the last movement of op 1, respectively `allegro molto' and `allegro con brio'. It's pretty obvious to me which performance more epitomises those instructions, top-class though both are.

One interesting thing I think I have discovered from the liner-note here is the origin of a recurrent theme in the writings of Richter's supporters' club. Richter is often said to possess and exhibit a capacity for exceptional `unity', or some equivalent expression, in his accounts. This will seem highly questionable to any listener for whom the sense of unity in a work of music is a matter for the composer in all ways that count, not for the interpreter. The concept seems to date back to Richter's understandably enthusiastic teacher Neuhaus. What I believe the expression meant from Neuhaus was that when Richter offered a novel interpretation he could sustain the novelty in a coherent way. What I believe the expression means from those who have subsequently recycled it is precisely nothing. There is any amount of true gold to be found in the work of this colossus of the 20th century piano, but we need to be prepared to think about it and exercise our critical faculties and not to find mares' nests and repeat meaningless formulae. Richter has left us very little Brahms, and I am only too grateful for what I have here. These are probably not pieces that give scope for the kind of insights that make Richter one of the ultimate greats, and if they don't give scope for that we should not pretend to be finding it. This is another major memorial to a unique artist, unique not least in his unpredictability. Where he has surprised me this time is in being so mainstream.

![Kobert - Off the Hook (2011) [Hi-Res] Kobert - Off the Hook (2011) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772434077_lnz36qc7wmx6u_600.jpg)

![Teresa Brewer - In London (2016) [Hi-Res] Teresa Brewer - In London (2016) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2021-03/1617164538_teresa-brewer-in-london-2016.jpg)

![Julius Hemphill - Dogon A.D. (Remastered) (1972/2026) [Hi-Res] Julius Hemphill - Dogon A.D. (Remastered) (1972/2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772427281_cover.png)

![Ben Williams - No Words. (Between Church & State instrumentals)(2026) [Hi-Res] Ben Williams - No Words. (Between Church & State instrumentals)(2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-03/04/cq7j2c1y36lc3fseqjfx3r2qi.jpg)

![Mehmet Ali Sanlikol - The Electric Oud Man Speaks and You Listen... (2026) [Hi-Res] Mehmet Ali Sanlikol - The Electric Oud Man Speaks and You Listen... (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/28/0areq907i6p8nj96306jai1a0.jpg)