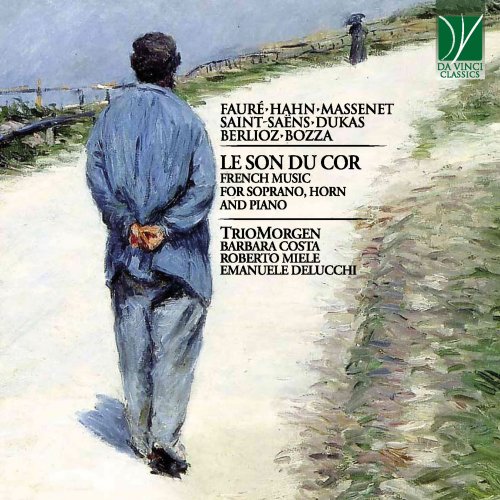

Barbara Costa, Emanuele Delucchi, Roberto Miele, TrioMorgen - Fauré, Hahn, Massenet, Saint-Saëns, Dukas, Berlioz, Bozza: Le son du cor (2020)

Artist: Barbara Costa, Emanuele Delucchi, Roberto Miele, TrioMorgen

Title: Fauré, Hahn, Massenet, Saint-Saëns, Dukas, Berlioz, Bozza: Le son du cor

Year Of Release: 2020

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless

Total Time: 01:04:55

Total Size: 237 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Fauré, Hahn, Massenet, Saint-Saëns, Dukas, Berlioz, Bozza: Le son du cor

Year Of Release: 2020

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless

Total Time: 01:04:55

Total Size: 237 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. 2 Duets, Op. 10 No. 2, Tarentelle

02. 3 Songs, Op. 8 No. 1 in C-Sharp Minor, Au bord de l'eau

03. Romance in F Major, Op. 36

04. Danse macabre in G Minor, Op. 40

05. Pleurs d'or, Op. 72

06. Morceau de concert, Op. 94

07. Les yeux clos

08. Quand je fus pris au pavillon in F-Sharp Major

09. Etudes latines No. 7, Tyndaris

10. Villanelle

11. Le jeune patre breton in E-Flat Major, H. 65

12. 2 songs, Op. 46 No. 2, Clair de lune

13. Amour benis

14. En foret, Op. 40

15. Trois melodies, Op. 7 No. 1, Apres un reve

16. La Damnation de Faust, Op. 24, H. 111, Act IV D'amour l'ardente flamme (Marguerite)

Playing with timbre and with the specific and idiosyncratic features of instruments and voices is one of the most fascinating aspects of musical composition. Even though it is always dangerous to simplistically equate one sensorial sphere with another, undeniably many musicians and listeners are tempted to define timbre as the “colour” of music. “The notes” may be seen as the drawing underlying a composition; but this is brought to life only when timbre is added. In turn, virtually no instrument has “one” timbre, and even though listeners familiar with the Western tradition will easily recognize a particular instrument’s timbre, it is also true that every instrument and every human voice possesses an entire timbral palette of its own. Moreover, from the interaction of two or more instruments and voices many more timbral combinations and possibilities blossom, which the skilled composer can adroitly exploit, sometimes in a very surprising fashion.

Seen from a certain viewpoint, it might be argued that the French horn’s timbre may represent a kind of point of encounter between the piano and the human voice. The combination of voice and piano is one of the most frequently employed in the history of music: the piano can provide for the harmonic support and musical frame needed by the human voice whose melodic potential is unequalled. Clearly enough, pianos can acquire a “singing” quality under the fingers of very gifted pianists; however, they are and remain instruments based on a percussive principle, and the impossibility to sustain the sound or to produce a vibrato is a condition painfully felt by many pianists. On the other hand, the human voice can create an extreme variety of sounds, including some which may be no less pointed and harsh than the most brutal piano sound; however, in most cases to “sing” is to smoothly sustain a tune, and an accomplished singer will be able to play with every single note precisely in the fashion which is unattainable by even the best pianists. The French horn shares many qualities with the human voice: both are based on breathing, both are capable of modifying a tone’s sound, volume or intonation during its entire duration, and both may be characterized by a particular roundness of timbre, a mellow quality which inspires and soothes the listener. On the other hand, the French horn’s range is much wider than that of the human voice, and the horn’s capability to articulate every sound in a very clear fashion brings it rather close to the piano.

In spite of all this, these three means of sound production are not frequently found together. Voice and piano, as said, is a beloved combination; French horn and piano is a less common pairing, but which boasts many masterpieces; voice and French horn are combined in countless arias from the operatic or oratorio repertoire. In this Da Vinci Classics album, these three partners continuously interact, at times all together, at times two by two; however, even when one of the three is temporarily missing, its presence continues to be felt, thanks to the astute choice of all the pieces recorded here.

The repertoire comes entirely from the French tradition (“French” indicating here much more than a nationality, which is in fact not shared by all composers; it is rather a mode of being and a school of thought). And it is common knowledge that the French were particularly fascinated by timbre: Hector Berlioz (represented here by two of his works) was one of the greatest orchestrators of all times, and Maurice Ravel (who is not represented here but whose presence is acutely felt in the most modern of these pieces) was his worthy successor. Between these two musicians, however, many other French composers are unanimously acknowledged as being among the greatest geniuses of timbre: Camille Saint-Saëns, represented here by three pieces, is another case in point, but many more could be cited.

It comes as no wonder, therefore, that this compilation includes some of the finest examples of the French tradition of the mélodie, the French counterpart to the German Lied, and that the treatment of the French horn in some of these pieces reaches levels of exquisite refinement. The programme opens with Tarentelle op. 10 no. 2 by Gabriel Fauré. Originally a vocal duet with piano accompaniment, set to lyrics by Marc Monnier, this piece is dedicated to Claudie Chamerot and Marianne Viardot, the two daughters of Pauline Viardot. Fauré was in love with Marianne at that time, and this may explain the extreme care he took in setting to music this seemingly unpretentious poem; the result is a brilliant, enthralling and exciting piece, where all musicians can display their value while, at the same time, having fun together. Au bord de l’eau op. 8 no. 1, by the same composer, could not be more different from the preceding piece; here, the contemplation of water flowing under the poet’s eyes becomes a symbol for the transience and fleetingness of life. The lyrics come from the pen of Sully Prudhomme, and Fauré had discovered them almost by chance; evidently, they inspired him to compose this piece whose tight musical structure seems indeed to “flow” effortlessly from the composer’s creative imagination, but whose extreme harmonic and melodic refinement reveals instead his extreme mastery of compositional techniques.

The very title of Saint-Saëns’ Romance op. 36 shows that the composer was considering the French horn as akin to the human voice; indeed, it is the singing quality of this instruments which comes to the fore throughout this short but touching work, and the accompaniment is as discreet and as delicate as possible. The compositional style clearly alludes to that of a Song without Words, and the choice to include it within this album is entirely consistent with the overall concept of the programme. As if trying to counterbalance it, the following piece by Saint-Saëns, a song on lyrics by Henri Cazalis, seems to treat the human voice as an instrument. Saint-Saëns was clearly aware of this feature: indeed, he later turned this song into an extremely famous orchestral piece, relinquishing the words in favour of very daring timbral explorations.

The Dance of Death, in which two distinct though close traditions merge (that of Halloween night and the medieval danse macabre) is represented in the orchestral version through thrilling and efficacious timbral ideas, including the use of the xylophone to symbolize the rattling bones of the skeletons.

The following piece was also initially a vocal duet. Gabriel Fauré wrote Pleurs d’Or op. 72 on lyrics by Albert Samain, originally titled Larmes – but Fauré changed the piece’s name because he had already composed another mélodie by the same title. The main musical idea structuring the piece is a stroke of genius: the waving accompaniment in 12/8 is punctuated by syncopated notes, gently dripping from the pianist’s fingers like “golden tears”. The overall atmosphere is seducing, caressing, and exquisitely romantic. By way of contrast with the other piece for French horn by Saint-Saëns recorded here, the Morceau de concert (existing in two versions, one with orchestral accompaniment) is a highly virtuosic and spectacular piece, created by the composer in dialogue with Henri Chaussier, one of the greatest horn players of the time. Chaussier had designed an omnitonic horn of his own invention, responding to what he perceived as the drawbacks of the German valve horns; Saint-Saëns fully endorsed his friend’s innovations and this brilliant work is almost a demonstration of their potential.

The musical language of Jules Massenet’s Les yeux clos is a skillful combination of typical topoi indicating hope and grief, desire and deception: the ascending triadic arpeggios suggest longing, while the descending chromaticism is a symbol for pain. An entirely different kind of love is depicted in Quand je fus pris au pavillon by Reynaldo Hahn, a picturesque, colourful and slightly ironic representation of a coup de foudre. The other song by the same composer, Tyndaris on lyrics by Leconte de Lisle, belongs instead in a collection of Etudes latines, inspired by a mythical classicising past, an exotic place of the soul imagined rather than remembered.

The use of reinterpreted ancient modes gives a mysterious and touching air to this masterpiece of a mélodie. Similar to Saint-Saëns’ Romance, also Paul Dukas’ Villanelle for horn reveals its vocal inspiration since its very title, alluding to a traditional vocal genre found in Renaissance Italy. A very virtuosic and brilliant piece, written for the final examinations of the Paris Conservatoire (1906), it gives the players the possibility of displaying the full range of their technical skill without renouncing a charming musicality. Another kind of “picturesque” imagination is that found in Berlioz’s Le jeune pâtre Breton, a mélodie originally scored for French horn, voice and piano. Here the horn represents the enchantment of nature, and its tone and typical melodic movements are borrowed by the voice, in a continuing reciprocal exchange. Nature is evoked also in Fauré’s Clair de lune, on lyrics by Paul Verlaine (which would also inspire Debussy’s piano piece); the mystery of masquerading corresponds to the mystery of moonlight and of night, in a graceful and seducing atmosphere. Tenderness and longing are also expressed in Massenet’s Amours bénis, vividly depicting the increasing proximity of a loving couple. The voice sings at first in very broken phrases, while towards the end of the piece it conquers long melodic stretches, poignantly symbolizing the achieved unity. Another work written as an examination piece for the Paris Conservatoire is En Forêt by Eugène Bozza, and in turn it seems to eschew none of the difficulties of horn technique, from large intervals to trills and including the full palette of technical complexities. In spite of this, it is a beautiful composition evoking, once more, the sounds of nature and the horn’s tradition as a symbol for the woods, for hunting and for nature in general. To conclude this album, we find two more gems: Fauré’s Après un rêve op. 7 no. 1 is probably the most famous and best loved of his many songs, and recounts the unattainable reality of a dreamed love; and Berlioz’s D’amour l’ardente flamme, one of the most celebrated of his operatic arias, and an astonishing depiction of the contrasting feelings stirred in the soul by an impossible love. The unity of love symbolized in many of these pieces through musical strategies seems therefore to evoke (and to be evoked by) the unity of sound achieved by the two instruments with the voice: a unique aural experience, which becomes a touching and intense symbol for poetry itself.

![Abraham Réunion - Jaden an nou (2026) [Hi-Res] Abraham Réunion - Jaden an nou (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770745777_folder.jpg)

![Cannonball Adderley - Somethin' Else (1958) [2022 DSD256] Cannonball Adderley - Somethin' Else (1958) [2022 DSD256]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770877615_folder.jpg)