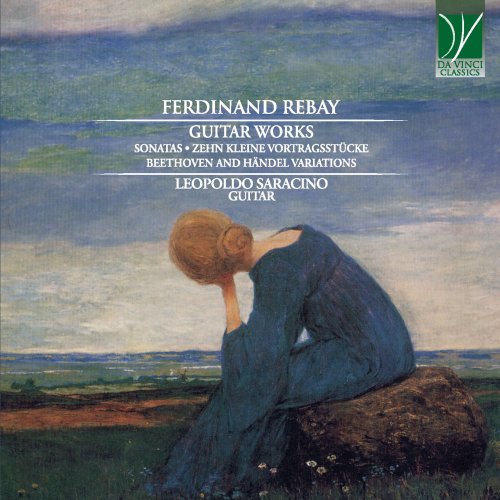

Leopoldo Saracino - Ferdinand Rebay: Guitar Works (2020)

Artist: Leopoldo Saracino

Title: Ferdinand Rebay: Guitar Works

Year Of Release: 2020

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless

Total Time: 01:01:32

Total Size: 245 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Ferdinand Rebay: Guitar Works

Year Of Release: 2020

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical Guitar

Quality: flac lossless

Total Time: 01:01:32

Total Size: 245 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

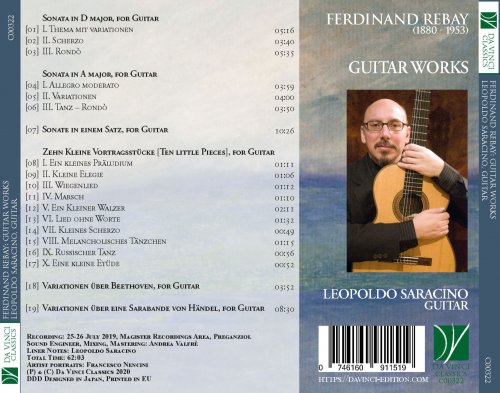

01. Sonate in D Major: I. Thema mit variationen

02. Sonate in D Major: II. Scherzo

03. Sonate in D Major: III. Rondò

04. Sonate in A für Gitarre: I. Allegro moderato

05. Sonate in A für Gitarre: II. Variationen

06. Sonate in A für Gitarre: III. Tanz-Rondò

07. Sonate in einem Satz

08. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 1, Ein kleines Präludium

09. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 2, Kleine Elegie

10. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 3, Wiegenlied

11. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 4, Marsch

12. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 5, Ein Kleiner Walzer

13. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 6, Lied ohne Worte

14. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 7, Kleines Scherzo

15. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 8, Melancholisches Tänzchen

16. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 9, Russischer Tanz

17. Zehn Kleine Vortragsstücke: No. 10, Eine kleine Etüde

18. Variationen über Beethoven

19. Variationen über eine Sarabande von Händel

Only in relatively recent times the figure of Ferdinand Rebay (Vienna, June 11th, 1880 – Vienna, November 6th, 1953) began to resurface from the oblivion in which it had remained for more than half a century. He was born in a very musical family: his father owned a music shop and his mother, a pianist, had studied with no less a musician than Anton Bruckner. Consequently, he received an excellent musical education: once he had learned to play the violin and the piano, he was admitted as a chorister in the Abbey of Heiligenkreuz, and, later, his cultural interests widened to include the study of visual arts (he obtained a specialist degree at the School of the Austrian Museum in Vienna). However, professional studies in the field of music remained at the core of his interests: in fact, he learnt to play the horn too and he started composing Lieder, choral and operatic music. In 1901 he entered the Conservatory of Vienna in the class of J. Hofmann, and, most importantly, in the class of composition led by the eminent pedagogue Robert Fuchs. Rebay’s work for symphonic orchestra, Erlkönig, which he presented for the completion of his studies in 1904, led Fuchs to affirm that in his twenty-nine years as a Conservatory teacher he had never seen a better work than that. This was not all: by that time, Rebay had already written about a hundred pieces in all the various genres. Strengthened by such an intense preparation, he was appointed at first to the direction of the Wiener Chorverein, and later of the Wiener Schubertbund. In 1920 he obtained the Chair of Piano at the Musikakademie; at the same time, he successfully continued his compositional activity, particularly in the field of vocal music. He wrote about a hundred choral works, at least four hundred Lieder and two operas. When the Nazis came to power in 1938, with the tragic Hitlerian Anschluss, Rebay fell into disgrace. He was removed from his prestigious office and even his pension was withdrawn. He died in 1953 in Vienna, in poverty and entirely forgotten.

With the exception of this bitter epilogue, Rebay’s career mirrors that of the ideal musician: a family environment filled with music, a complete education, a great culture, an indefatigable activity and prestigious appointments. According to what Fritz Niedermann wrote in 1953 for Rebay’s obituary on the journal Gitarrenfreund, Rebay composed around six hundred guitar works, both for solo guitar and in the field of chamber music. Rebay’s musical features are clearly marked by the Neoclassical traits characterizing the first half of the twentieth century, and are very far from the trends of the so-called Second Vienna School. His style is very personal and reminiscent of the Viennese atmospheres of that era. It includes the last echoes of a Germanic late Romanticism imbued with lyricism (as in the case of Richard Strauss), impressionistic and Ravelian ethereal atmospheres (one is reminded of the quartet and of the works for strings and piano by the great Maurice), as well as the clear Neoclassical and German connotations by Hindemith. In sum, this is the same artistic, cultural and musical substrate from which other names known well by the guitarists (such as those of Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Ponce) drew fully.

The three Sonatas opening this album are paradigmatic as concerns what has been said above, since they appear to have been clearly modelled upon the structure of the Sonata, i.e. the principal form of the Classical period, and, consequently, of the Neoclassical one. Following the most established tradition, in two of them the first movement is rigorously structured in Sonata form, even though it is articulated in a twentieth-century (or, if one prefers, in a modernist) fashion. The third Sonata, the Sonate in D marjor (1943), opening the collection of pieces on this album, begins instead with a “Theme and Variations”. This probably was Rebay’s favourite genre: it is not by chance that it is represented by two other significant examples in this recording. After a theme presented in mellow chords in the majestic key of D major (which is particularly incisive on the guitar, particularly when the sixth string is tuned one tone lower), six variations with a mutable and fantastic character unfold: the almost tarantella-like tempo of 6/8 in the last variation is not to be missed, since it is as unexpected as it is a stroke of genius. They are followed by a classical “Scherzo”, whose Trio curiously cites the same harmonic skeleton as the Scherzo of Beethoven’s Second Symphony op. 36. The Sonata is closed by a savoury “Rondò ”, which begins with parallel fourths vaguely reminiscent of Debussy-like exoticisms.

The “Allegro moderato” opening the Sonate in A major (1944) is instead structured, as said above, in the Sonata Form. Here, after a first theme which is as dark and dramatic as possible in the principal minor key, a second follows with a sweet change of tempo and in the key of C major. After the development section, traditionally dedicated to the re-elaboration of the material of the exposition, there is the reprise; here, in the coda, there is a deceptive representation of the first theme. The second movement is the inevitable Theme with variations; on this occasion, it is based upon the Volkslied “Schwesterlein, Schwesterlein, wann gehn wir nach Haus?”, which had once been harmonized and reworked also by Brahms. In fact, the influence of the great musician from Hamburg are not missing, particularly in the very suave fourth Variation. The Sonata is completed by a joking, almost humorous “Rondò”, playing on characteristic syncopations and accent displacements.

The Sonate in einem Satz (n.d.) is decidedly structured and articulated. In spite of its title, however, and of the numerous indications found over the staves, it is easy to identify four principal sections, even though they follow each other seamlessly. These are an initial “Allegro, ma non troppo” in the Sonata form, which is markedly solid and affirmative; an “Allegro molto” characterized by a dense and polyphonic style; then a dreamlike “Adagio” almost reminiscent of Ponce; and finally a decided and virile “Frisch bewegt”.

The Zehn kleine Vortragsstücke (1939) belong in a completely different genre. As it often happens with great composers, they hide true musical pearls with a great artistic inspiration behind their avowed pedagogical goals. This collection of album leaves is opened by Ein kleines Praeludium: a splendid E-major arpeggio closely reminiscent of the similar technical experiences by Villa-Lobos, while the Kleine Elegie, instead, unfolds a sad and touching tripartite melody. Wiegenlied is a sweet lullaby, followed by a contrasting Marsch with a grotesque and almost expressionistic character. The direct inspiration drawn from the great German Romantic composers connotes Ein kleinen Walzer (à la Schumann) – where, however, the impression is that of listening to Chopin – and the Lied ohne Worte (nach einem eigenen Lied), whose great harmonic refinement seems to come from Brahms’ pen. Virtuosity and popular folklore characterize the two pairs of concluding pieces.

At first there is a brilliant Kleines Scherzo, followed by a Melancholisches Tänzchen with a sad and vaguely gypsy pace; then the Russischer Tanz whose style is almost à la manière de Prokof’ev, and Eine kleine Etüde (chromatisches Perpetuum Mobile mit Quergriffen), a whirling etude on melodic and chordal chromaticism. Two series of Themes with Variations conclude the album’s programme. In the first, Sechs kleine Variationen über Beethoven’s Lied: “Das Blümchen Wunderhold” (1946), after the exposition of an innocent, candid and almost childlike motif, the affective temperature increasingly augments with every variation, up to the suggestive conclusion, rich in pathos. The second, Zehn Variationen über eine Sarabande in D moll von G. Fr. Händel (1944), is instead inspired by the well-known Sarabande from the Harpsichord Suite in d minor HWV 437 by the great Saxonian. Rebay must have particularly cherished this seducing piece; indeed, he realized a second transcription of it for two guitars. It is impossible to describe in a few words the extraordinary charm pervading every single variation, and the deep impression caused by the final, chromatically varied reprise of the fascinating initial incipit: it is simply a splendid piece, worthy of the theme’s solemnity, and to be listened in full.

It is difficult to understand the reasons why a composer of such a standing as Rebay could have remained forgotten for decades. Possibly, one reason is that the greatest disseminator of his guitar works, his niece Gerta Hammerschmidt (who was also the principal dedicatee of these pieces) did not have the necessary standing as a concert musician for adequately promoting and circulating his music. This does not apply to her much more famous colleague Luise Walker (1910-1998) who was in turn the dedicatee of some of Rebay’s works; unfortunately, she did not show interest in Rebay’s music. Another reason may be found in the great importance Rebay gave to chamber music with respect to the solo repertoire, thus failing to attract the attention of the most famous guitarists of the time (first of all Segovia), who were only inclined to solo performance. If we add to all this Rebay’s fall into disgrace at the dawn of the Nazi regime (with the consequent economic and social marginalisation); and, in the aftermath of World War II, his utter extraneousness to the rigorous dictates of Darmstadt’s musical theories (with the unavoidable and implacable exclusion from all the musically important elites) it is easy to understand why his music completely disappeared from the stages. It is a pity, because in his oeuvre the joining link between the nineteenth-century Italianate classical repertoire and the great Romantic tradition is found. A link which unfortunately has always been considered as missing from the history of the guitar: here, instead, we find the Brahms so sorely missed by the guitar.

![Marcela Arroyo & Quique Sinesi - Reflejos (2026) [Hi-Res] Marcela Arroyo & Quique Sinesi - Reflejos (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770728206_folder.jpg)

![Mal Waldron - Left Alone (Remastered 2014) (2026) [Hi-Res] Mal Waldron - Left Alone (Remastered 2014) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770802366_zssweohuxq7f9_600.jpg)

![Jake Mason Trio - The Modern Ark (2026) [Hi-Res] Jake Mason Trio - The Modern Ark (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770943321_ngffz4bzeqxax_600.jpg)

![Dobs Vye - Lounge Fever (2026) [Hi-Res] Dobs Vye - Lounge Fever (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770796125_lg5fka4etpbeq_600.jpg)