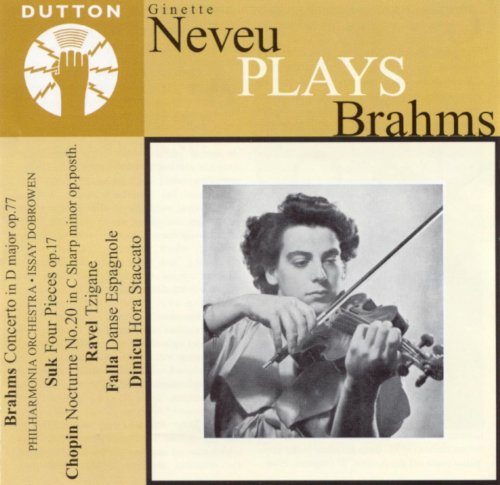

Ginette Neveu - Ginette Neveu Plays Brahms (2002)

Artist: Ginette Neveu

Title: Ginette Neveu Plays Brahms

Year Of Release: 2002

Label: Dutton

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log)

Total Time: 01:14:48

Total Size: 309 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Ginette Neveu Plays Brahms

Year Of Release: 2002

Label: Dutton

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log)

Total Time: 01:14:48

Total Size: 309 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

1-3: Brahms, Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77, London Philharmonia Orchestra, Issay Dobroven

4-7: Josef Suk, Pieces (4) for violin & piano, Op. 17, No.4, Burleska, Op. 17/4

4. Quasi ballata

5. Appassionata

6. Un poco triste

7. Burleska

8: Chopin, Nocturne for piano in C sharp minor (doubtful), KK Anh.Ia/6 Arr. Rodionov

9: Ravel, Tzigane, rhapsodie de concert, for violin & piano (or orchestra)

10: Fritz Kreisler, Danse Espagnole for violin & piano (transcription from Falla's La Vida Breve)

11: Jascha Heifetz, Hora staccato (After Grigoras Dinicu)

It is sad that Ginette Neveu made so few recordings before her untimely death in an aircraft accident in 1949. Walter Legge was quick off the mark after the end of the war, getting the then little-known French artist to record the Sibelius Violin Concerto in November 1945. Her studio recording of the Brahms followed in August 1946, but after that, despite the acclaim, her EMI recording career was limited to less demanding repertory by Chausson, Ravel, Debussy and Strauss. The Debussy offered here, recorded in March 1948, did not appear in Britain until it formed part of the LP listed above almost ten years later.

All the more reason to welcome this disc, which brings together that studio recording of the Debussy Sonata – a wonderfully volatile performance, vividly transferred but with fair surface hiss, not so smooth as EMI’s own transfer on References (8/90) – with live recordings made in the last 18 months of her life. It says much for her vitality and imagination in the studio, and her ability to convey spontaneity in her playing, that there is so little difference in interpretation between her EMI versions of the Brahms and the Ravel and those here.In each movement of the Brahms the performances are fractionally broader than the studio ones, a touch more fiery in the outer movements, even more intense in the slow movement. The playing may not always be quite so immaculate, and the more distant balance of the violin takes away some of the impact of the first-movement cadenza, but the tension in the audience is vividly conveyed, when, at the start of the heavenly coda following the cadenza, one registers a communal exhalation of breath, with, alas, some coughing.

The Ravel here comes in the composer’s own orchestral arrangement, where the studio recording was of the original piano version, yet the interpretation could hardly be more similar. The studio recording brings a bigger dynamic range, with exquisite pianissimos, but in the live Boston performance Neveu brings out the improvisatory quality of the writing even more compellingly, the Hungarian fire inspired by the playing of the charismatic Jelly d’Aranyi, whom Neveu plainly mirrors. Orchestral sound in both the Brahms and the Ravel is rather dim, and the recording of the Ravel has a low rumble as well as hiss, but that detracts not at all from the impact of the soloist’s playing.'

All the more reason to welcome this disc, which brings together that studio recording of the Debussy Sonata – a wonderfully volatile performance, vividly transferred but with fair surface hiss, not so smooth as EMI’s own transfer on References (8/90) – with live recordings made in the last 18 months of her life. It says much for her vitality and imagination in the studio, and her ability to convey spontaneity in her playing, that there is so little difference in interpretation between her EMI versions of the Brahms and the Ravel and those here.In each movement of the Brahms the performances are fractionally broader than the studio ones, a touch more fiery in the outer movements, even more intense in the slow movement. The playing may not always be quite so immaculate, and the more distant balance of the violin takes away some of the impact of the first-movement cadenza, but the tension in the audience is vividly conveyed, when, at the start of the heavenly coda following the cadenza, one registers a communal exhalation of breath, with, alas, some coughing.

The Ravel here comes in the composer’s own orchestral arrangement, where the studio recording was of the original piano version, yet the interpretation could hardly be more similar. The studio recording brings a bigger dynamic range, with exquisite pianissimos, but in the live Boston performance Neveu brings out the improvisatory quality of the writing even more compellingly, the Hungarian fire inspired by the playing of the charismatic Jelly d’Aranyi, whom Neveu plainly mirrors. Orchestral sound in both the Brahms and the Ravel is rather dim, and the recording of the Ravel has a low rumble as well as hiss, but that detracts not at all from the impact of the soloist’s playing.'

![DJ Harrison - ElectroSoul (2026) [Hi-Res] DJ Harrison - ElectroSoul (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769008544_ivamsuaz889ub_600.jpg)

![Björn Meyer - Convergence (2026) [Hi-Res] Björn Meyer - Convergence (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769000420_u6sqqe0hy9chb_600.jpg)