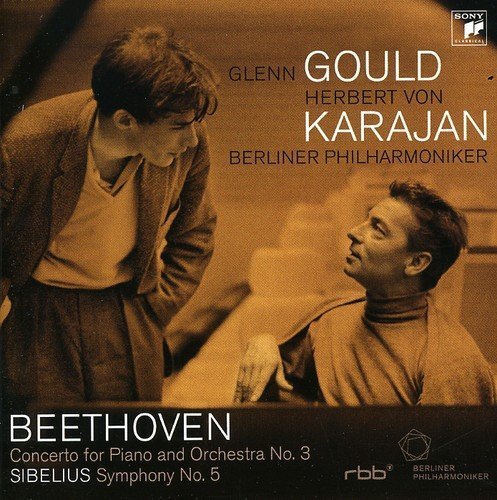

Glenn Gould, Herbert von Karajan - Beethoven: Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 3, Sibelius: Simphony No. 5 (2008)

Artist: Glenn Gould, Herbert von Karajan

Title: Beethoven: Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 3 / Sibelius: Simphony No. 5

Year Of Release: 2008

Label: Sony Classical

Genre: Classical

Quality: APE (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 66:26

Total Size: 332 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Beethoven: Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 3 / Sibelius: Simphony No. 5

Year Of Release: 2008

Label: Sony Classical

Genre: Classical

Quality: APE (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 66:26

Total Size: 332 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827)

Concerto for piano and orchestra No. 3 c-moll Op. 37

01. I. Allegro con brio

02. II. Largo

03. III. Rondo (Allegro)

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

Simphony No. 5 Es-Dur Op. 82

04. I. Tempo Molto Moderato – Allegro moderato – Vivace molto – Presto – Più Presto

05. II. Andante Mosso, quasi Allegretto

06. III. Allegro Molto – Misterioso – Un Pochettino - Largamente – Un Pochettino Stretto

Performers:

Glenn Gould - piano

Berliner Philharmoniker

Herbert von Karajan

Live recording, May 26, 1957

The mutual admiration society that was Glenn Gould and Herbert von Karajan gave six concerts between May 1957 and September 1959 featuring Beethoven’s C minor Concerto (Berlin 1957) and Bach’s D minor (Berlin 1958, Lucerne 1959). Though neither of the Bach performances has appeared on disc, the Beethoven has had several CD outings. This handsomely packaged “official” transfer by Sony is the best we have had technically.

Gould had a distinctive range of personae where the Beethoven was concerned. His 1955 Canadian radio performance was described by Bryce Morrison as “coltish and spine-tingling”, the very reverse of the studiously intense, intimately scaled studio recording Gould made with Leonard Bernstein in 1959. This more conventionally paced Berlin performance is notable for the sense it brings of the work’s incipient lyric beauty. At Karajan’s more flowing tempo, Gould’s account of the Largo has an airier, more improvisatory feel.

The Sibelius comes from the same concert. This was Karajan’s first Sibelius with the BPO two years after taking over the orchestra. He was a dedicated Sibelian whose Philharmonia recordings Sibelius himself thought remarkable. The Berliners, by contrast, had played little Sibelius under Furtwängler, nor were German audiences much enamoured of the music. (Witness the oddly tepid response of the audience who clearly don’t know whether the symphony has finished or not.)

So Karajan had a struggle on his hands. Thanks to patches of fine string-playing and the sheer force of his advocacy there are moments of greatness here in what is often a strangely costive realisation. Taking the orchestra forward from this pit of incomprehension to the multi-faceted splendours of the legendary 1965 DG Berlin Fifth was some journey.

Gould had a distinctive range of personae where the Beethoven was concerned. His 1955 Canadian radio performance was described by Bryce Morrison as “coltish and spine-tingling”, the very reverse of the studiously intense, intimately scaled studio recording Gould made with Leonard Bernstein in 1959. This more conventionally paced Berlin performance is notable for the sense it brings of the work’s incipient lyric beauty. At Karajan’s more flowing tempo, Gould’s account of the Largo has an airier, more improvisatory feel.

The Sibelius comes from the same concert. This was Karajan’s first Sibelius with the BPO two years after taking over the orchestra. He was a dedicated Sibelian whose Philharmonia recordings Sibelius himself thought remarkable. The Berliners, by contrast, had played little Sibelius under Furtwängler, nor were German audiences much enamoured of the music. (Witness the oddly tepid response of the audience who clearly don’t know whether the symphony has finished or not.)

So Karajan had a struggle on his hands. Thanks to patches of fine string-playing and the sheer force of his advocacy there are moments of greatness here in what is often a strangely costive realisation. Taking the orchestra forward from this pit of incomprehension to the multi-faceted splendours of the legendary 1965 DG Berlin Fifth was some journey.

![Tim Richards - Tim Richards Hextet Telegraph Hill (2018) [Hi-Res] Tim Richards - Tim Richards Hextet Telegraph Hill (2018) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766996852_rqnxdiia2f5nc_600.jpg)

![Johnny Janis - Playboy Presents... Once In a Blue Moon (2015) [Hi-Res] Johnny Janis - Playboy Presents... Once In a Blue Moon (2015) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/29/hpechfkz7kpvyn01p0qdae2u4.jpg)

![Bárbara Callejas & Giovanni Cultrera - Sesiones En Vivo Quinteto (2025) [Hi-Res] Bárbara Callejas & Giovanni Cultrera - Sesiones En Vivo Quinteto (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766740203_dh7dkl6rvri9t_600.jpg)