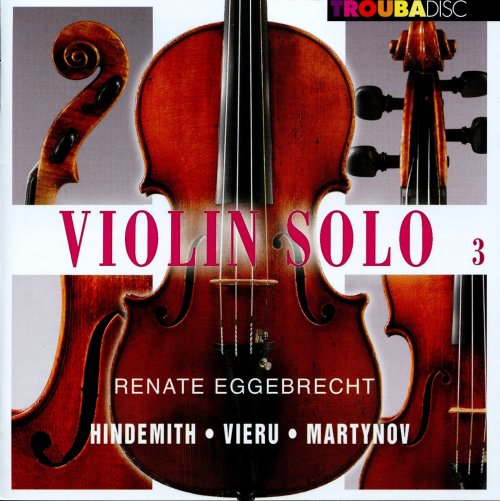

Renate Eggebrecht - Violin Solo, Vol. 3 (2012)

Artist: Renate Eggebrecht

Title: Violin Solo, Vol. 3

Year Of Release: 2012

Label: Troubadisc

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:18:02

Total Size: 435 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Violin Solo, Vol. 3

Year Of Release: 2012

Label: Troubadisc

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:18:02

Total Size: 435 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Studien (Paul Hindemith)

1. I. Allegretto 10:09

2. II. Praludium (Fragment) 00:27

Violin Sonata in G minor, Op. 11, No. 6 (Paul Hindemith)

3. I. Massig schnell 03:27

4. II. Siziliano: Massig bewegt 05:23

5. III. Finale: Lebhaft 05:16

Violin Sonata: Satz und Fragment (Paul Hindemith)

6. I. Presto 00:59

7. II. Fragment 01:08

Violin Sonata, Op. 31, No. 1 (Paul Hindemith)

8. I. Sehr lebhafte Achtel 01:36

9. II. Sehr langsame Viertel 03:14

10. III. Sehr lebhafte Viertel 01:59

11. IV. Intermezzo, Lied 01:45

12. V. Prestissimo 02:03

Violin Sonata, Op. 31, No. 2, 'Es ist so schones Wetter draussen' (Paul Hindemith)

13. I. Leicht bewegte Viertel 01:33

14. II. Ruhig bewegte Achtel 02:38

15. III. Gemachliche Viertel 01:12

16. IV. 5 Variationen uber deas lied "Komm, lieber Mai" 04:10

Capriccio (Anatol Vieru)

17. Capriccio 04:11

Partita (Vladimir Ivanovich Martinov)

18. Partita: I. - 06:39

19. Partita: II. - 03:57

20. Partita: III. - 04:48

21. Partita: IV. - 03:18

22. Partita: V. - 03:53

23. Partita: VI. - 04:17

Performers:

Renate Eggebrecht, violin

Renate Eggebrecht has been busy preparing and recording 20th century solo violin music for a few years now, and this is volume 3 of a mounting catalogue of remarkable and often neglected works by often quite well known composers. This disc concentrates all of Paul Hindemith’s work for solo violin on one disc, including four world premiere recordings and leaving enough space for some substantial works by composers of which I had not heard.

The opening of Hindemith’s early Allegretto study is reproduced on the inside of the jewel case liner for this disc, and virtually unplayable it looks as well. The music is a kind of manic waltz, with about every kind of double-stop imaginable. This is followed by an unfinished fragment which lasts less than 30 seconds, but both items show the composer exploring the extremes of the violin while a student at the Frankfurt Conservatory.

The Sonata Op.11 no.6 was only discovered in its complete form in 2002. The musical language of this piece shows the young composer still working more with the technical aspects of the instrument rather than achieving much in the way of a personal style, though Hindemith’s virtuosity and inventive precociousness is clearly apparent. There is a good deal of wandering around in the second movement Siciliano, and as with the Studien the double stopping and range is a killer. Eggebrecht’s intonation fights a little to keep everything together at times, and is stretched further in a lively Finale.

The Sonata fragments which follow are from some time in the first half of the 1920s, and are certainly more distinctive in terms of an already remarkable personal language. The manic wide vibrato or glissandi of the Presto are quite something, and the melodic shapes of the following fragment make one wonder why the piece was abandoned.

Hindemith’s own instrument was of course the viola, and the Op. 31 sonatas were written for his violinist quartet colleagues rather than for his own use. The finish and sense of commitment in these pieces is a little in question, at least two of the movements in the first of the pair and the Sonata No.2 having been jotted down during a train journey, but this also serves to illustrate Hindemith’s swift imagination and flexibility. Both sonatas employ lyrical song forms, the final movement of the second sonata even quoting a Mozart song. The first sonata extends asymmetrical melodic patterns to the extent that structure appears distorted in even quite compact movement durations, but the Hindemith fingerprint intervals and gestures are more often present. The Sonata No.2 is less intense, having a sunnier, more pastoral feel than the first from the start. This is also reflected in the title of the first movement "...Es ist so schönes Wetter draußen" ("... it's such beautiful weather outside"). The final variations on Mozart’s “Komm, lieber Mai” come as quite a surprise, and as a point of programming lead nicely into the next piece.

Anatol Vieru came from the Romanian province of Moldovia, and studied with Aram Khachaturian in Moscow. Using folk music as a base, his avant-gardism is recognised as having a quietly subversive character, and this is also a characteristic of the brief Capriccio. There are a number of techniques listed in the booklet notes, but the end result is that it sounds like more than one violinist at work at several points in the piece, left-hand pizzicato playing an interesting role. The Capriccio is a compact and satisfying work with its own substance and life, though I’m sure it would work well as a surprise encore.

Vladimir Martynov is another unfamiliar name to me, and his Partita of 1976 is unlike any of the other pieces on the disc. Kerstin Holm describes it as “raw, Russian Minimal Music with arte-povera appeal” in the booklet notes, and this sums up the general impression very well. The actual musical material is quite folk-like and basic, but with repetition of a basic phrase with variations each movement and the piece as a whole has quite a hypnotic quality. The opening of the third movement is almost a direct quote – at least in terms of gesture – of Terry Riley’s ‘In C’. It would be interesting to take this kind of material and extend it with some of Steve Reich’s phasing techniques, or explore the canonic effects of layering the music, but as it stands this piece is great fun. Either that or it will drive you up the wall and back down again, but I happened to quite like it. Martynov argues that anyone still composing music in the conventional sense in these days of computer DJ-ing is ‘nothing but a clown.’ His loss: I can see the point but, having done both, would say live and let live.

The SACD sound quality on this disc is very good indeed, making a sonic feast of what threatens to be something of a strain on the brain and ears. The resonance seemed to sound quite different on different systems, and at times I was tempted to thin everything back to stereo for clarity’s sake, but the violin tone and presence is always very fine indeed. Where I do have a few problems is in Renate Eggebrecht’s technical abilities in the worst excesses of the Hindemith. I’m more inclined to blame the composer for expecting purity of music to come out of such a minefield of double-stopping and extreme intervals, but either way it doesn’t seem to have been much ‘fun’ to record some of these pieces, and this is also the impression left on the listener. The fascination of hearing such rare and unusual repertoire outweighs these considerations however, and those fascinated by Hindemith’s admittedly finer solo viola sonatas should also be encouraged to explore his violin repertoire – if only to find out how he seemed to seek revenge on his violinist colleagues in the early years! -- Dominy Clements,

The opening of Hindemith’s early Allegretto study is reproduced on the inside of the jewel case liner for this disc, and virtually unplayable it looks as well. The music is a kind of manic waltz, with about every kind of double-stop imaginable. This is followed by an unfinished fragment which lasts less than 30 seconds, but both items show the composer exploring the extremes of the violin while a student at the Frankfurt Conservatory.

The Sonata Op.11 no.6 was only discovered in its complete form in 2002. The musical language of this piece shows the young composer still working more with the technical aspects of the instrument rather than achieving much in the way of a personal style, though Hindemith’s virtuosity and inventive precociousness is clearly apparent. There is a good deal of wandering around in the second movement Siciliano, and as with the Studien the double stopping and range is a killer. Eggebrecht’s intonation fights a little to keep everything together at times, and is stretched further in a lively Finale.

The Sonata fragments which follow are from some time in the first half of the 1920s, and are certainly more distinctive in terms of an already remarkable personal language. The manic wide vibrato or glissandi of the Presto are quite something, and the melodic shapes of the following fragment make one wonder why the piece was abandoned.

Hindemith’s own instrument was of course the viola, and the Op. 31 sonatas were written for his violinist quartet colleagues rather than for his own use. The finish and sense of commitment in these pieces is a little in question, at least two of the movements in the first of the pair and the Sonata No.2 having been jotted down during a train journey, but this also serves to illustrate Hindemith’s swift imagination and flexibility. Both sonatas employ lyrical song forms, the final movement of the second sonata even quoting a Mozart song. The first sonata extends asymmetrical melodic patterns to the extent that structure appears distorted in even quite compact movement durations, but the Hindemith fingerprint intervals and gestures are more often present. The Sonata No.2 is less intense, having a sunnier, more pastoral feel than the first from the start. This is also reflected in the title of the first movement "...Es ist so schönes Wetter draußen" ("... it's such beautiful weather outside"). The final variations on Mozart’s “Komm, lieber Mai” come as quite a surprise, and as a point of programming lead nicely into the next piece.

Anatol Vieru came from the Romanian province of Moldovia, and studied with Aram Khachaturian in Moscow. Using folk music as a base, his avant-gardism is recognised as having a quietly subversive character, and this is also a characteristic of the brief Capriccio. There are a number of techniques listed in the booklet notes, but the end result is that it sounds like more than one violinist at work at several points in the piece, left-hand pizzicato playing an interesting role. The Capriccio is a compact and satisfying work with its own substance and life, though I’m sure it would work well as a surprise encore.

Vladimir Martynov is another unfamiliar name to me, and his Partita of 1976 is unlike any of the other pieces on the disc. Kerstin Holm describes it as “raw, Russian Minimal Music with arte-povera appeal” in the booklet notes, and this sums up the general impression very well. The actual musical material is quite folk-like and basic, but with repetition of a basic phrase with variations each movement and the piece as a whole has quite a hypnotic quality. The opening of the third movement is almost a direct quote – at least in terms of gesture – of Terry Riley’s ‘In C’. It would be interesting to take this kind of material and extend it with some of Steve Reich’s phasing techniques, or explore the canonic effects of layering the music, but as it stands this piece is great fun. Either that or it will drive you up the wall and back down again, but I happened to quite like it. Martynov argues that anyone still composing music in the conventional sense in these days of computer DJ-ing is ‘nothing but a clown.’ His loss: I can see the point but, having done both, would say live and let live.

The SACD sound quality on this disc is very good indeed, making a sonic feast of what threatens to be something of a strain on the brain and ears. The resonance seemed to sound quite different on different systems, and at times I was tempted to thin everything back to stereo for clarity’s sake, but the violin tone and presence is always very fine indeed. Where I do have a few problems is in Renate Eggebrecht’s technical abilities in the worst excesses of the Hindemith. I’m more inclined to blame the composer for expecting purity of music to come out of such a minefield of double-stopping and extreme intervals, but either way it doesn’t seem to have been much ‘fun’ to record some of these pieces, and this is also the impression left on the listener. The fascination of hearing such rare and unusual repertoire outweighs these considerations however, and those fascinated by Hindemith’s admittedly finer solo viola sonatas should also be encouraged to explore his violin repertoire – if only to find out how he seemed to seek revenge on his violinist colleagues in the early years! -- Dominy Clements,

![Fabiano do Nascimento - Vila (2026) [Hi-Res] Fabiano do Nascimento - Vila (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/26/o4t38f6qf24pvc3bqzanbhsz3.jpg)

![El Calefón - Salir Del Agujero (2026) [Hi-Res] El Calefón - Salir Del Agujero (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/26/sm3fq4x280rjvn4eh85ksne6j.jpg)

![Martin Listabarth Trio - In Her Footsteps (2026) [Hi-Res] Martin Listabarth Trio - In Her Footsteps (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771946819_folder.jpg)