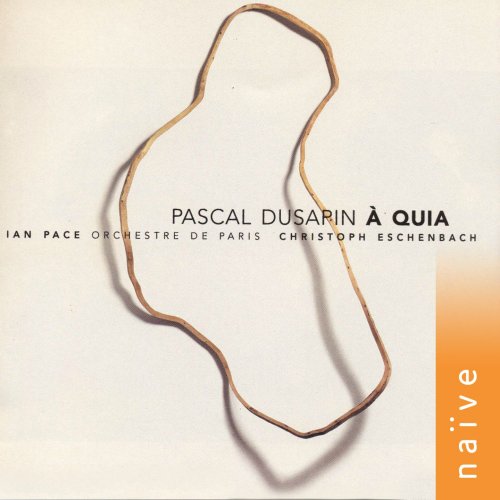

Ian Pace, Orchestre De Paris, Christoph Eschenbach - Pascal Dusapin: À Quia (2003)

Artist: Ian Pace, Orchestre De Paris, Christoph Eschenbach

Title: Pascal Dusapin: À Quia

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: Naive

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:22:54

Total Size: 286 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Pascal Dusapin: À Quia

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: Naive

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:22:54

Total Size: 286 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

CD 1

7 Études Pour Piano

1. Étude No. 1 11:11

2. Étude No. 2 5:35

3. Étude No. 3 9:47

4. Étude No. 4 4:47

5. Étude No. 5 11:06

6. Étude No. 6 5:01

7. Étude No. 7 8:15

CD 2

À Quia [Concerto Pour Piano Et Orchestre]

1. I 8:55

2. II 6:57

3. III 11:21

Performers:

Piano – Ian Pace

Orchestre De Paris

Conductor – Christoph Eschenbach

A landmark recording for contemporary music, and equally as a demonstration of the marvellous potential of new ways to communicate musical experience; as ground-breaking in its different way as the Duchable/Nelson inter-active DVDs of the Beethoven concertos hailed last week.

Pascal Dusapin (b. 1955) is an important French composer in this post-Messiaen era, his music still relatively unfamiliar in UK, but becoming known through an increasing discography.

His piano concerto À quia was commissioned by the City of Bonn for the 175th anniversary of Beethoven's death. It is a piano concerto like unto none other, and the seven études constitute a set of preparatory studies for its composition, entirely different in purpose from the twentieth century studies of, say, Debussy and Ligeti.

Dusapin is an intuitive composer, who explores feelings in a language all his own. Here, we are helped to enter his world with written commentaries in the notes, but also, at once haltingly and fluently, in the filmed rehearsals and explanations. The French expression "reduire quelq'un à quia" is about feeling confusion, lassitude and inability to find words. The concerto À quia gropes for areas of feeling worlds away from Beethoven's positive and goal directed music; sadness, impotence, helplessness!

The studies, commissioned by four pianists and originally carrying titles of games, were completed immediately before composing the concerto (or is it an anti-concerto?). They often sound improvisatory as they begin, worrying away at small figures, sometimes just a couple of notes, with obsessive fixation and repetitions. I heard Origami, Igra, Tangram & Mikado, the first four of the then projected series of seven studies each named after a game, when they were shared amongst three very different pianists in a marathon Nuit de Piano at Strasbourg, Ian Pace the most flamboyantly virtuosic in the two fast and finger-knotting studies Igra and Mikardo.

The concerto is unlikely to enter the regular repertoire, but the études should be rewarding for enterprising pianists and a few of them would grace any exploratory piano recital; I see them as developing aspects of the innovative piano writing of Giacinto Scelsi*, avant-garde and far before his time in the 1950s, and still too infrequently heard.

Dusapin in his filmed talks touches on the many different ways to listen to music, or to hear it. I listened to the concerto first, finding it both intriguing and bewildering. Next, the studies with which I became impatient, especially with seemingly endless repetitions of single notes. They are best not listened to straight through; later, replaying them whilst otherwise occupied, they 'crept in' and I found myself more sympathetic to their way of communicating and developing ideas. One inescapable analogy was how an Indian singer or sitarist explores the notes of a rag - Dusapin draws upon elements of folk music from Greece and the Arab world.

For newcomers to Dusapin's music the DVD will be the core of the experience. The rehearsals of the studies are shown in an atmosphere of intimacy, a roving, searching camera eavesdropping with us into a private, completely unscripted event. We discover that the music is far from improvisational; Dusapin is precise in his requirements and Pace works to them in an atmosphere of trusting confidence, quite free of tension. To end the DVD, he plays two of the studies complete, Dusapin at his side as page-turner.

Ian Pace is an omnivorous devourer of music demanding 'transcendental pianism'. He is given to marathon solo recitals in which his astonishing sight reading skills and speed of assimilation remind one of John Ogdon's, sometimes at the expense of refinement of tone. Here there is no question of his command of expressive subtleties and tonal beauty; it is marvellous piano playing.

Dusapin's comments during rehearsal of the concerto help us to find a way into the unusual relationship between soloist and orchestra, with the piano sometimes alone and 'totally helpless', seeking to express itself by 'trying to merge' with the orchestra.

The DVD is absorbing and moving to watch and gives us invaluable insights into this music and these musicians impossible through words alone. One slightly incongruous distraction is the additional presence of a glamorous artist, sitting quietly sketching composer and pianist; what implied sub-text might there be? And one regret is that beyond occasional glimpses of the scores, we are not able to have sustained views of some pages, to follow the music as we can in those interactive Ambroisie Beethoven DVDs, recommended above and again here as abslutely not to be missed.

Film and sound quality is superb throughout and this is a fine production from what we discover is quite a large production team. Buy this, even if you are not 'into' cutting-edge new music, and you will enjoy as you learn, and gradually absorb music which rewards the time spent in its company.

The score of the seven études (Salabert EAS 20135) is recommended as an adjunct to listening and study. It is clear, easy to follow and invaluable for following the subtlety and precision of Dusapin's writing. It has a fascinating Foreword by Ian Pace, who discusses the variety of touch/articulation and pedalling required for a satisfactory performance of these works.

Pascal Dusapin (b. 1955) is an important French composer in this post-Messiaen era, his music still relatively unfamiliar in UK, but becoming known through an increasing discography.

His piano concerto À quia was commissioned by the City of Bonn for the 175th anniversary of Beethoven's death. It is a piano concerto like unto none other, and the seven études constitute a set of preparatory studies for its composition, entirely different in purpose from the twentieth century studies of, say, Debussy and Ligeti.

Dusapin is an intuitive composer, who explores feelings in a language all his own. Here, we are helped to enter his world with written commentaries in the notes, but also, at once haltingly and fluently, in the filmed rehearsals and explanations. The French expression "reduire quelq'un à quia" is about feeling confusion, lassitude and inability to find words. The concerto À quia gropes for areas of feeling worlds away from Beethoven's positive and goal directed music; sadness, impotence, helplessness!

The studies, commissioned by four pianists and originally carrying titles of games, were completed immediately before composing the concerto (or is it an anti-concerto?). They often sound improvisatory as they begin, worrying away at small figures, sometimes just a couple of notes, with obsessive fixation and repetitions. I heard Origami, Igra, Tangram & Mikado, the first four of the then projected series of seven studies each named after a game, when they were shared amongst three very different pianists in a marathon Nuit de Piano at Strasbourg, Ian Pace the most flamboyantly virtuosic in the two fast and finger-knotting studies Igra and Mikardo.

The concerto is unlikely to enter the regular repertoire, but the études should be rewarding for enterprising pianists and a few of them would grace any exploratory piano recital; I see them as developing aspects of the innovative piano writing of Giacinto Scelsi*, avant-garde and far before his time in the 1950s, and still too infrequently heard.

Dusapin in his filmed talks touches on the many different ways to listen to music, or to hear it. I listened to the concerto first, finding it both intriguing and bewildering. Next, the studies with which I became impatient, especially with seemingly endless repetitions of single notes. They are best not listened to straight through; later, replaying them whilst otherwise occupied, they 'crept in' and I found myself more sympathetic to their way of communicating and developing ideas. One inescapable analogy was how an Indian singer or sitarist explores the notes of a rag - Dusapin draws upon elements of folk music from Greece and the Arab world.

For newcomers to Dusapin's music the DVD will be the core of the experience. The rehearsals of the studies are shown in an atmosphere of intimacy, a roving, searching camera eavesdropping with us into a private, completely unscripted event. We discover that the music is far from improvisational; Dusapin is precise in his requirements and Pace works to them in an atmosphere of trusting confidence, quite free of tension. To end the DVD, he plays two of the studies complete, Dusapin at his side as page-turner.

Ian Pace is an omnivorous devourer of music demanding 'transcendental pianism'. He is given to marathon solo recitals in which his astonishing sight reading skills and speed of assimilation remind one of John Ogdon's, sometimes at the expense of refinement of tone. Here there is no question of his command of expressive subtleties and tonal beauty; it is marvellous piano playing.

Dusapin's comments during rehearsal of the concerto help us to find a way into the unusual relationship between soloist and orchestra, with the piano sometimes alone and 'totally helpless', seeking to express itself by 'trying to merge' with the orchestra.

The DVD is absorbing and moving to watch and gives us invaluable insights into this music and these musicians impossible through words alone. One slightly incongruous distraction is the additional presence of a glamorous artist, sitting quietly sketching composer and pianist; what implied sub-text might there be? And one regret is that beyond occasional glimpses of the scores, we are not able to have sustained views of some pages, to follow the music as we can in those interactive Ambroisie Beethoven DVDs, recommended above and again here as abslutely not to be missed.

Film and sound quality is superb throughout and this is a fine production from what we discover is quite a large production team. Buy this, even if you are not 'into' cutting-edge new music, and you will enjoy as you learn, and gradually absorb music which rewards the time spent in its company.

The score of the seven études (Salabert EAS 20135) is recommended as an adjunct to listening and study. It is clear, easy to follow and invaluable for following the subtlety and precision of Dusapin's writing. It has a fascinating Foreword by Ian Pace, who discusses the variety of touch/articulation and pedalling required for a satisfactory performance of these works.

DOWNLOAD FROM ISRA.CLOUD

Ian Pace Orchestre De Paris Christoph Eschenbach Pascal Dusapin À Quia 03 2211.rar - 286.4 MB

Ian Pace Orchestre De Paris Christoph Eschenbach Pascal Dusapin À Quia 03 2211.rar - 286.4 MB

![Ex Novo Ensemble - OSVALDO COLUCCINO: Emblema (2018) [Hi-Res] Ex Novo Ensemble - OSVALDO COLUCCINO: Emblema (2018) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/22/ot6pocjri3hisq06iz4768yl5.jpg)