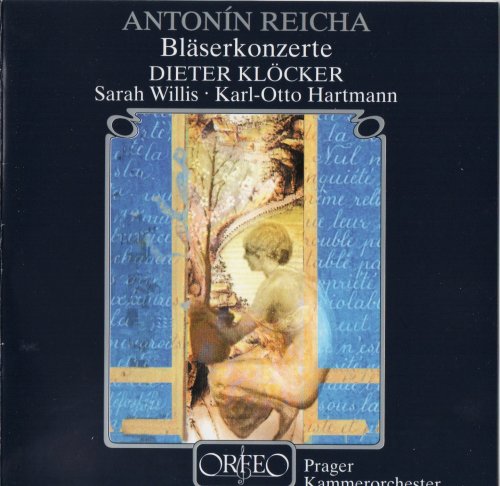

Dieter Klöcker, Sarah Willis, Karl-Otto Hartmann - Antonín Rejcha: Wind Concertos (2002)

Artist: Dieter Klöcker, Sarah Willis, Karl-Otto Hartmann

Title: Antonín Rejcha: Wind Concertos

Year Of Release: 2002

Label: Orfeo

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 58:23

Total Size: 308 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Antonín Rejcha: Wind Concertos

Year Of Release: 2002

Label: Orfeo

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (image+.cue,log,scans)

Total Time: 58:23

Total Size: 308 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Antonín Rejcha (1770-1836)

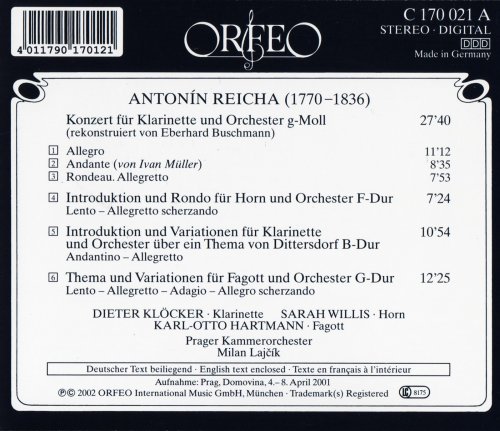

01. Konzert für Klarinette G-moll: I. Allegro [0:11:14.57]

02. Konzert für Klarinette G-moll: II. Andante [0:08:37.25]

03. Konzert für Klarinette G-moll: III. Rondeau [0:07:56.13]

04. Introduktion und Rondo F-Dur [0:07:27.00]

05. Introduktion und Variationen für Klarinette B-Dur [0:10:57.00]

06. Thema und Variationen für Fagott G-Dur [0:12:25.50]

Performers:

Dieter Klöcker - clarinet

Sarah Willis - horn

Karl-Otto Hartmann - bassoon

Prague Chamber Orchestra

Milan Lajčik - conductor

While Joseph Haydn is almost universally acknowledged as the inventor of the string quartet, Antonín Reicha (1770–1836), a contemporary of Beethoven, is generally credited with being the inventor of the wind quintet, elevating it to a position of respect and prominence that would rival that of the string quartet. The quintets aside, there are many other works of Reicha that have disappeared from view in the century-and-a-half plus since his death. The son of a military Kapellmeister, Reicha faced an uncertain future following his father’s death in 1771. After some basic musical instruction, the boy exhibited a gift for music. Eventually his uncle took custody of him, relocating the boy to the court of Oettingen-Wallerstein, where he was adopted by his uncle, given a loving home environment and a broad-based education that included musical instruction with one of Reicha’s compatriots, Antonín Rössler, also known as Antonio Rosetti.

The environment at Oettingen-Wallerstein was one of the most artistically encouraging in Europe and provided young Antonín with instruction in German and French. The latter would serve the Bohemian well in the years to come. He later went to Bonn where he met the young Beethoven. The exceptional quality of the court wind players in Bonn awakened Reicha’s interest in the solo possibilities of winds, but there were more pressing matters. The political earthquake known as the French Revolution was also felt in Bonn, eventually resulting in Reicha’s resignation and relocation to Hamburg and then Paris in 1799. Here Reicha enjoyed long-term success and contact with famous wind virtuosos and professors at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique. Reicha joined the faculty of the institution in 1818.

Even though Reicha enjoyed close associations with a number of leading wind virtuosos in Paris, he wrote for only a handful. Among these was the Estonian-born clarinetist Iwan Müller (1786–1854), whose playing had attracted attention continent-wide. Müller was preoccupied—perhaps obsessed is a better term—with furthering the technical capabilities of the instrument. Upon his arrival in Paris in 1809, Müller ignited a firestorm of controversy among clarinet players with his radical ideas, resulting in the establishment of the traditional camps of advocates and detractors. Müller was universally praised for his “beautiful tone, brilliant technique, elegant manner of articulation, as well as the fire of his performances.”

Among the major orchestrally accompanied works for winds that have survived are an incomplete concerto written in 1815 for Müller’s “new and improved” clarinet, which Reicha referred to as la clarinette perfectionnée. Intended to improve technical facility as well as tone production, this was a 12-key modified version of the six-keyed instrument used by Xavier Lefèvre. Unfortunately, the only manuscript source for this important early Romantic work is incomplete and a reconstruction was required for this recording. The second movement is missing, and for this recording Dieter Klöcker has substituted the central movement from the third of Müller’s seven concertos. In the esthetic sense, this works quite well, given what Klöcker terms “the stylistic proximity of this movement to Reicha, the contrasting key of E? and the movement’s weight.” While the entire clarinet part is notated for the finale, the score ends abruptly at measure 125, so further work had to be done in order to prepare this performing edition. The task was undertaken by Klöcker’s colleague, Eberhard Buschmann. Buschmann was already familiar with the style from his years as a member of Klöcker’s Consortium Classicum, but he further studied Reicha’s idiom and painstakingly filled in the blanks, completing the score for this recording.

The remaining works on this Orfeo release are of less stature, but nonetheless of great importance when developing the time line of the repertoire for each instrument. Reicha’s colleague at the Conservatoire, Frédéric Blasius (1758–1829), was a virtuoso clarinetist and also the dedicatee of the variations. Blasius chose to append an introduction to Dittersdorf’s theme and Reicha’s subsequent variations. The Introduction and Rondo for Horn and the Theme and Variations for Bassoon were also penned for Parisian virtuosos with whom Reicha was acquainted.

First, let me unequivocally state that none of these works are what anyone would term great music, but they are significant and important contributions to the repertoire for the instruments. Each composition demonstrates Reicha’s grasp of form, his knowledge of the capabilities of each instrument, and his ability to craft music of appropriate weight. The strongest of the pieces is the clarinet concerto. Even without the substitution of the Andante from one of Müller’s concertos for the missing or lost slow movement, the fragmented concerto emerges as an important document in the development of the clarinet as it fills a gap—albeit a narrowing one—between the Mozart concerto and those of Spohr and Weber. The variations elicit high marks from me as well; they are models of their kind, crafted with confidence, and posing what surely were formidable technical challenges for the original performers.

Dieter Klöcker and his soloist colleagues from Consortium Classicum are unquestionably first-class, technically and expressively. Klöcker receives top billing here since his performances occupy almost three-quarters of the release. He is—as always—in top form. Those unfamiliar with Klöcker’s performances may find the sound a bit unusual, but it is due in large part to the construction of his century-old Oehler clarinet, not to mention the use of a wooden mouthpiece and string to secure the reed thereto. Klöcker’s technique is—in a word—imposing; I sat spellbound and overcome by both the beautifully controlled sound he produces and his incredible agility. The enviable ease of execution by Klöcker and his colleagues is fused to an insightful understanding of the idiom and the music. The resultant performances are generous in energy and rhythmic impetus, and while the repertoire may lack the spark of genius found in Mozart’s works for wind instruments, the music will consistently and repeatedly reward the ear via Reicha’s art and these definitive performances. -- Michael Carter

The environment at Oettingen-Wallerstein was one of the most artistically encouraging in Europe and provided young Antonín with instruction in German and French. The latter would serve the Bohemian well in the years to come. He later went to Bonn where he met the young Beethoven. The exceptional quality of the court wind players in Bonn awakened Reicha’s interest in the solo possibilities of winds, but there were more pressing matters. The political earthquake known as the French Revolution was also felt in Bonn, eventually resulting in Reicha’s resignation and relocation to Hamburg and then Paris in 1799. Here Reicha enjoyed long-term success and contact with famous wind virtuosos and professors at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique. Reicha joined the faculty of the institution in 1818.

Even though Reicha enjoyed close associations with a number of leading wind virtuosos in Paris, he wrote for only a handful. Among these was the Estonian-born clarinetist Iwan Müller (1786–1854), whose playing had attracted attention continent-wide. Müller was preoccupied—perhaps obsessed is a better term—with furthering the technical capabilities of the instrument. Upon his arrival in Paris in 1809, Müller ignited a firestorm of controversy among clarinet players with his radical ideas, resulting in the establishment of the traditional camps of advocates and detractors. Müller was universally praised for his “beautiful tone, brilliant technique, elegant manner of articulation, as well as the fire of his performances.”

Among the major orchestrally accompanied works for winds that have survived are an incomplete concerto written in 1815 for Müller’s “new and improved” clarinet, which Reicha referred to as la clarinette perfectionnée. Intended to improve technical facility as well as tone production, this was a 12-key modified version of the six-keyed instrument used by Xavier Lefèvre. Unfortunately, the only manuscript source for this important early Romantic work is incomplete and a reconstruction was required for this recording. The second movement is missing, and for this recording Dieter Klöcker has substituted the central movement from the third of Müller’s seven concertos. In the esthetic sense, this works quite well, given what Klöcker terms “the stylistic proximity of this movement to Reicha, the contrasting key of E? and the movement’s weight.” While the entire clarinet part is notated for the finale, the score ends abruptly at measure 125, so further work had to be done in order to prepare this performing edition. The task was undertaken by Klöcker’s colleague, Eberhard Buschmann. Buschmann was already familiar with the style from his years as a member of Klöcker’s Consortium Classicum, but he further studied Reicha’s idiom and painstakingly filled in the blanks, completing the score for this recording.

The remaining works on this Orfeo release are of less stature, but nonetheless of great importance when developing the time line of the repertoire for each instrument. Reicha’s colleague at the Conservatoire, Frédéric Blasius (1758–1829), was a virtuoso clarinetist and also the dedicatee of the variations. Blasius chose to append an introduction to Dittersdorf’s theme and Reicha’s subsequent variations. The Introduction and Rondo for Horn and the Theme and Variations for Bassoon were also penned for Parisian virtuosos with whom Reicha was acquainted.

First, let me unequivocally state that none of these works are what anyone would term great music, but they are significant and important contributions to the repertoire for the instruments. Each composition demonstrates Reicha’s grasp of form, his knowledge of the capabilities of each instrument, and his ability to craft music of appropriate weight. The strongest of the pieces is the clarinet concerto. Even without the substitution of the Andante from one of Müller’s concertos for the missing or lost slow movement, the fragmented concerto emerges as an important document in the development of the clarinet as it fills a gap—albeit a narrowing one—between the Mozart concerto and those of Spohr and Weber. The variations elicit high marks from me as well; they are models of their kind, crafted with confidence, and posing what surely were formidable technical challenges for the original performers.

Dieter Klöcker and his soloist colleagues from Consortium Classicum are unquestionably first-class, technically and expressively. Klöcker receives top billing here since his performances occupy almost three-quarters of the release. He is—as always—in top form. Those unfamiliar with Klöcker’s performances may find the sound a bit unusual, but it is due in large part to the construction of his century-old Oehler clarinet, not to mention the use of a wooden mouthpiece and string to secure the reed thereto. Klöcker’s technique is—in a word—imposing; I sat spellbound and overcome by both the beautifully controlled sound he produces and his incredible agility. The enviable ease of execution by Klöcker and his colleagues is fused to an insightful understanding of the idiom and the music. The resultant performances are generous in energy and rhythmic impetus, and while the repertoire may lack the spark of genius found in Mozart’s works for wind instruments, the music will consistently and repeatedly reward the ear via Reicha’s art and these definitive performances. -- Michael Carter

![Compro Oro - Lamellomania (2026) [Hi-Res] Compro Oro - Lamellomania (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/29/z9k9v7p2kvdnm71ct3xbsyljw.jpg)

![Galliano - Unreliable Memories Of Contested Conversations (2026) [Hi-Res] Galliano - Unreliable Memories Of Contested Conversations (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769761649_bch472vhc4xxi_600.jpg)

![Klara Cloud & the Vultures - Baroque (2026) [Hi-Res] Klara Cloud & the Vultures - Baroque (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1769692901_x5lcf3x5ubcfc_600.jpg)