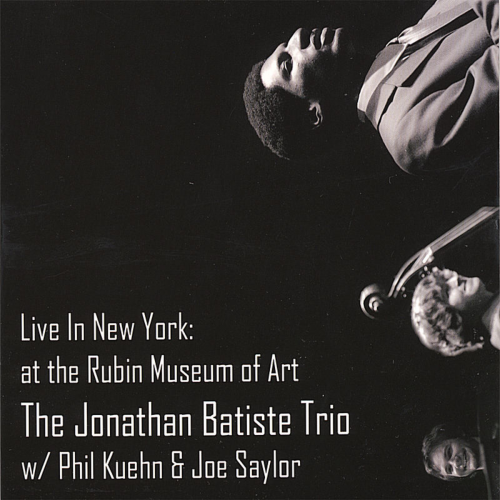

The Jonathan Batiste Trio - Live In New York: At The Rubin Museum Of Art (2007)

Artist: The Jonathan Batiste Trio

Title: Live In New York: At The Rubin Museum Of Art

Year Of Release: 2007

Label: Jonathan Batiste

Genre: Jazz Piano Trio, Mainstream Jazz, New Orleans

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 00:47:43

Total Size: 293 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Live In New York: At The Rubin Museum Of Art

Year Of Release: 2007

Label: Jonathan Batiste

Genre: Jazz Piano Trio, Mainstream Jazz, New Orleans

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 00:47:43

Total Size: 293 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Sumayra (07:47)

2. Kindergarten (06:11)

3. Virupa (The Ugly One): Movement 1 (06:07)

4. Moon River (06:35)

5. Jen's Blues (07:40)

6. Red Beans (07:29)

7. Green Chimneys (05:51)

Near the end of his concert at the Rubin Museum of Art on Friday, the pianist Jonathan Batiste played a piece about a six-inch statue, which sat across the stage from him on a pedestal. It was a representation of Virupa the Ugly, an ancient Tibetan yogi. For its Friday-night jazz series the museum commissions musicians to interact with the Himalayan art in its collection and write original music inspired by it.

Mr. Batiste said that his piece was the last section of a three-part composition he wrote for the statue. It was dark-toned post-Coltrane mainstream jazz, with a couple of dramatic mood shifts; a dense, torrid middle section; and some open space for improvising by Mr. Batiste and two other gifted, young and driven soloists: the tenor saxophonist Matt Marantz and the alto saxophonist Eddie Barbash.

But the piece couldn’t touch what Mr. Batiste and his quintet did when the underlying force of the music was Thelonious Monk or Duke Ellington, or just the will to entertain. In placing him, you have to talk about region and influence. Mr. Batiste, born in 1986, comes from New Orleans. He has a clear connection to the sound of Wynton Marsalis’s rhythm sections, but an even deeper connection to Marcus Roberts, the pianist in Mr. Marsalis’s bands during some of the 1980s and ’90s.

This means that he favors streamlined, attention-to-detail rhythm, deep but often played with light accents. (The bassist Phil Kuehn and the drummer Ulysses Owens helped him, swinging cleanly; the unamplified acoustics of the room helped them all.) It also means that, as with Mr. Roberts, Mr. Batiste doesn’t draw much of his sustenance from the harmonic vocabulary of 1960s jazz pianists: he looks to earlier models all the way back to Scott Joplin and within himself, where there’s outgoing humor and eccentric showmanship.

He can show off, and occasionally does. A long detour through Joplin’s “Entertainer” in his piece “In the Night” seemed unnecessarily impressive. But he opened with really likable guile: playing the melodica, a child’s keyboard wind instrument, he circled the theater improvising variations on Monk’s “’Round Midnight,” preaching on the song, running fast patterns on it, making it complicated and beautiful.

And in his “Sumayra,” a playful piece with a fast-trickling melody, some well-worn chord changes in the bridge and a walking bass line, Mr. Batiste was stunning: he played a solo in the piano’s upper region that was spare, forceful, witty, funky, imaginative and coherent. He seemed free, as if he weren’t trying to score points on depth and modernity but just squeezing juice out of the song; and thoughtful, as if walking in slow motion. It wasn’t a tour de force, and somehow it was better for it.

Mr. Batiste said that his piece was the last section of a three-part composition he wrote for the statue. It was dark-toned post-Coltrane mainstream jazz, with a couple of dramatic mood shifts; a dense, torrid middle section; and some open space for improvising by Mr. Batiste and two other gifted, young and driven soloists: the tenor saxophonist Matt Marantz and the alto saxophonist Eddie Barbash.

But the piece couldn’t touch what Mr. Batiste and his quintet did when the underlying force of the music was Thelonious Monk or Duke Ellington, or just the will to entertain. In placing him, you have to talk about region and influence. Mr. Batiste, born in 1986, comes from New Orleans. He has a clear connection to the sound of Wynton Marsalis’s rhythm sections, but an even deeper connection to Marcus Roberts, the pianist in Mr. Marsalis’s bands during some of the 1980s and ’90s.

This means that he favors streamlined, attention-to-detail rhythm, deep but often played with light accents. (The bassist Phil Kuehn and the drummer Ulysses Owens helped him, swinging cleanly; the unamplified acoustics of the room helped them all.) It also means that, as with Mr. Roberts, Mr. Batiste doesn’t draw much of his sustenance from the harmonic vocabulary of 1960s jazz pianists: he looks to earlier models all the way back to Scott Joplin and within himself, where there’s outgoing humor and eccentric showmanship.

He can show off, and occasionally does. A long detour through Joplin’s “Entertainer” in his piece “In the Night” seemed unnecessarily impressive. But he opened with really likable guile: playing the melodica, a child’s keyboard wind instrument, he circled the theater improvising variations on Monk’s “’Round Midnight,” preaching on the song, running fast patterns on it, making it complicated and beautiful.

And in his “Sumayra,” a playful piece with a fast-trickling melody, some well-worn chord changes in the bridge and a walking bass line, Mr. Batiste was stunning: he played a solo in the piano’s upper region that was spare, forceful, witty, funky, imaginative and coherent. He seemed free, as if he weren’t trying to score points on depth and modernity but just squeezing juice out of the song; and thoughtful, as if walking in slow motion. It wasn’t a tour de force, and somehow it was better for it.

Download Link Isra.Cloud

The Jonathan Batiste Trio - Live In New York: At The Rubin Museum Of Art (2007)

My blog

The Jonathan Batiste Trio - Live In New York: At The Rubin Museum Of Art (2007)

My blog

![Magda Mayas' Filamental - Murmur (2026) [Hi-Res] Magda Mayas' Filamental - Murmur (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771663724_i3cjtptz4ae2l_600.jpg)