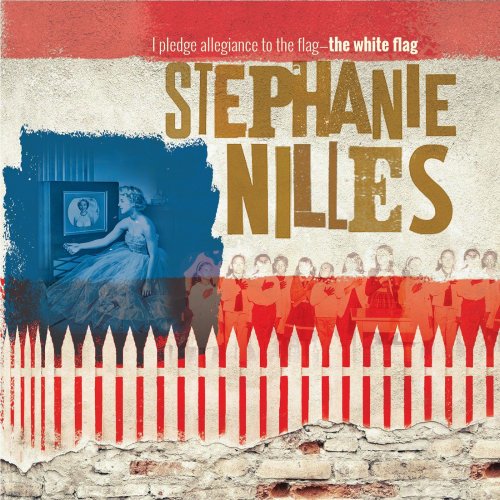

Stephanie Nilles - I Pledge Allegiance to The Flag - The White Flag (2021) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Stephanie Nilles

Title: I Pledge Allegiance to The Flag - The White Flag

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Sunnyside Records

Genre: Jazz

Quality: Mp3 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks) / 24bit-96kHz FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:14:32

Total Size: 171 / 258 MB / 1.21 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: I Pledge Allegiance to The Flag - The White Flag

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Sunnyside Records

Genre: Jazz

Quality: Mp3 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks) / 24bit-96kHz FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:14:32

Total Size: 171 / 258 MB / 1.21 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Fables of Faubus (13:11)

2. East Coasting (4:09)

3. Oh Lord Don't Let Them Drop That Atomic Bomb On Me (5:06)

4. O.P. (3:42)

5. Goodbye Pork Pie Hat (7:05)

6. Free Cell Block F, 'Tis Nazi U.S.A (5:56)

7. Devil Woman (6:43)

8. Peggy's Blue Skylight (5:31)

9. Pithecanthropus Erectus (9:21)

10. Remember Rockefeller at Attica (4:47)

11. Alabama (9:05)

Among the many issues that still plague the United States is its seemingly unending betrayal of its Black population. Though the struggle against prejudice in the States continues, the complexion of its fighters continues to change, as broader swathes of the American public begin to pick up the mantle of racial justice and equality for all.

The voices of African American militants continue to ring in the vanguard’s ears. One such musical example is the late, great bassist/composer Charles Mingus, whose music was vehemently charged with indignation concerning the rights of the downtrodden. His messages, both outright and nuanced, are touchstones for many musicians who choose to address these issues, including singer-songwriter/pianist Stephanie Nilles, who interprets Mingus’s canon on her new recording, I pledge allegiance to the flag – the white flag.

Born six years after Mingus’s death, Nilles comes from a world removed from that of her muse. She is a white woman who grew up in the suburbs of Chicago and studied classical piano and cello. Nilles’s initial introduction to jazz came through her younger brother’s bass study and his involvement with a summer jazz orchestra. It was through her brother that her ears first caught the sounds of Mingus’s “Jump Monk,” igniting a spark that would catch up with her down the line.

Nilles continued her study of music at the Cleveland Institute of Music, where the strict classical environment strengthened her musical chops but left her no closer to jazz. From Cleveland, Nilles moved to New York City where she spent some time away from music, working odd jobs and as a research assistant at Yeshiva University’s Center for Ethics. As many musical friends began to descend upon New York to attend graduate school, Nilles began to get pulled back into music making, beginning to write, improvise and play various shows around the City. An important mentor during Nilles’s reemergence was violinist/activist/educator Christian Howes. He was instrumental in helping her branch out from her rigid classical education toward the improvisational freedom of jazz.

The music of Mingus began to appear in Nilles’s repertory in 2007, the bassist’s particular blend of intricacy with bombast and humor with anger was intoxicating. Nilles took to the road for a time, playing gigs where she could, until she ended up in New Orleans, where she became involved with the eclectic local music scene, including a quartet with bassist Jesse Morrow, a devout follower of Mingus. Special moments with Mingus’s music ensued, including the mourning of a friend who died from cancer with a cathartic “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” sendoff. Nilles soon had an entire set of Mingus pieces that she could play solo, an exhausting but exhilarating feat.

In May 2019, Nilles performed a transcription of saxophonist Charles McPherson’s solo on Mingus’s “OP” on a series of solo concerts in Germany. Radio Bremen producer Volker Steppat heard this and was immediately impressed. Steppat asked if Nilles would be interested in recording an entire album of solo performed Mingus material, which she was ecstatic to try.

The recording was made in December 2019 at the Sendesaal in Bremen, Germany, the same hall that Mingus had performed his first German concert with his classic Sextet of Eric Dolphy, Clifford Jordan, Johnny Coles, Jaki Byard and Dannie Richmond nearly 55 years earlier. Most of the pieces were recorded in first or second takes.

The program begins with Nilles’s dramatic take on “Fables of Faubus,” Mingus’s inflammatory composition about Governor Orval Faubus’s illegal order prohibiting the desegregation of public schools in Arkansas is given a broad treatment where the pianist injects her own classical influences and a stark reminder of the piece’s intent with a quotation of the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” The pianist takes the cosmopolitan swing of “East Coasting” and adds an element of the natural with bits of bird song in the piece’s sonatina like arrangement. Done in one take, the languidly paced “Oh Lord, Don’t Let Them Drop That Atomic Bomb on Me” is a study of building tension through controlled chaos. The McPherson solo on “OP” is the transcription that launched the project and a joyous, yet terrifyingly electric piece, that feels like it is going faster as it slows, much like a Liszt étude.

The stolid “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” is played as a solemn funereal dirge and with open, near empty voicings, another sad reminder of the piece being written about a black man who died prematurely. Mingus’s iconic “Free Cell Block F, ‘Tis Nazi USA” is a difficult piece that demands attention with its quick pace and strong drive but it is also one of the composer’s classic wolf-in-sheep’s clothing political statement songs where the tune’s meaning is only discerned from learning its title. Nilles’s study of blues players and walking basslines (a concept not developed in a classical music education) helped in her approach to the offbeat blues of “Devil Woman.” French impressionism informs Nilles’s arrangement of “Peggy’s Blue Skylight,” the piece shimmering more so through her glassy piano touch.

The bassist’s “Pithecanthropus Erectus” provides challenges for solo piano renditions, as the horn led melody is full of swelling attack, but Nilles proves up to the challenge, providing a moving rendition echoing a feeling of uncertainty that Mingus implied on society’s evolution or devolution. Though “Remember Rockefeller at Attica” could be played by a straight-laced conservative jazzer, the tune’s irony is only felt when its discordance is let loose in a flurry of raging note clusters that Nilles is willing to provide. The album concludes with John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” the saxophonist’s heartbreaking ode to the young victims of the 1963 bombing of the 16h Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, played as a minimalistic epilogue.

It is hard not to be moved by the singularly brilliant voice of Charles Mingus. In reinterpreting his tunes and those of other Black voices, Stephanie Nilles knows that she is privileged and remains sensitive. She also knows that the fight against racism is a universal cause and that the power of Mingus’s work artistically assists that cause, thus the creation of her moving new recording, I pledge allegiance to the flag – the white flag.

The voices of African American militants continue to ring in the vanguard’s ears. One such musical example is the late, great bassist/composer Charles Mingus, whose music was vehemently charged with indignation concerning the rights of the downtrodden. His messages, both outright and nuanced, are touchstones for many musicians who choose to address these issues, including singer-songwriter/pianist Stephanie Nilles, who interprets Mingus’s canon on her new recording, I pledge allegiance to the flag – the white flag.

Born six years after Mingus’s death, Nilles comes from a world removed from that of her muse. She is a white woman who grew up in the suburbs of Chicago and studied classical piano and cello. Nilles’s initial introduction to jazz came through her younger brother’s bass study and his involvement with a summer jazz orchestra. It was through her brother that her ears first caught the sounds of Mingus’s “Jump Monk,” igniting a spark that would catch up with her down the line.

Nilles continued her study of music at the Cleveland Institute of Music, where the strict classical environment strengthened her musical chops but left her no closer to jazz. From Cleveland, Nilles moved to New York City where she spent some time away from music, working odd jobs and as a research assistant at Yeshiva University’s Center for Ethics. As many musical friends began to descend upon New York to attend graduate school, Nilles began to get pulled back into music making, beginning to write, improvise and play various shows around the City. An important mentor during Nilles’s reemergence was violinist/activist/educator Christian Howes. He was instrumental in helping her branch out from her rigid classical education toward the improvisational freedom of jazz.

The music of Mingus began to appear in Nilles’s repertory in 2007, the bassist’s particular blend of intricacy with bombast and humor with anger was intoxicating. Nilles took to the road for a time, playing gigs where she could, until she ended up in New Orleans, where she became involved with the eclectic local music scene, including a quartet with bassist Jesse Morrow, a devout follower of Mingus. Special moments with Mingus’s music ensued, including the mourning of a friend who died from cancer with a cathartic “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” sendoff. Nilles soon had an entire set of Mingus pieces that she could play solo, an exhausting but exhilarating feat.

In May 2019, Nilles performed a transcription of saxophonist Charles McPherson’s solo on Mingus’s “OP” on a series of solo concerts in Germany. Radio Bremen producer Volker Steppat heard this and was immediately impressed. Steppat asked if Nilles would be interested in recording an entire album of solo performed Mingus material, which she was ecstatic to try.

The recording was made in December 2019 at the Sendesaal in Bremen, Germany, the same hall that Mingus had performed his first German concert with his classic Sextet of Eric Dolphy, Clifford Jordan, Johnny Coles, Jaki Byard and Dannie Richmond nearly 55 years earlier. Most of the pieces were recorded in first or second takes.

The program begins with Nilles’s dramatic take on “Fables of Faubus,” Mingus’s inflammatory composition about Governor Orval Faubus’s illegal order prohibiting the desegregation of public schools in Arkansas is given a broad treatment where the pianist injects her own classical influences and a stark reminder of the piece’s intent with a quotation of the Black national anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing.” The pianist takes the cosmopolitan swing of “East Coasting” and adds an element of the natural with bits of bird song in the piece’s sonatina like arrangement. Done in one take, the languidly paced “Oh Lord, Don’t Let Them Drop That Atomic Bomb on Me” is a study of building tension through controlled chaos. The McPherson solo on “OP” is the transcription that launched the project and a joyous, yet terrifyingly electric piece, that feels like it is going faster as it slows, much like a Liszt étude.

The stolid “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat” is played as a solemn funereal dirge and with open, near empty voicings, another sad reminder of the piece being written about a black man who died prematurely. Mingus’s iconic “Free Cell Block F, ‘Tis Nazi USA” is a difficult piece that demands attention with its quick pace and strong drive but it is also one of the composer’s classic wolf-in-sheep’s clothing political statement songs where the tune’s meaning is only discerned from learning its title. Nilles’s study of blues players and walking basslines (a concept not developed in a classical music education) helped in her approach to the offbeat blues of “Devil Woman.” French impressionism informs Nilles’s arrangement of “Peggy’s Blue Skylight,” the piece shimmering more so through her glassy piano touch.

The bassist’s “Pithecanthropus Erectus” provides challenges for solo piano renditions, as the horn led melody is full of swelling attack, but Nilles proves up to the challenge, providing a moving rendition echoing a feeling of uncertainty that Mingus implied on society’s evolution or devolution. Though “Remember Rockefeller at Attica” could be played by a straight-laced conservative jazzer, the tune’s irony is only felt when its discordance is let loose in a flurry of raging note clusters that Nilles is willing to provide. The album concludes with John Coltrane’s “Alabama,” the saxophonist’s heartbreaking ode to the young victims of the 1963 bombing of the 16h Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, played as a minimalistic epilogue.

It is hard not to be moved by the singularly brilliant voice of Charles Mingus. In reinterpreting his tunes and those of other Black voices, Stephanie Nilles knows that she is privileged and remains sensitive. She also knows that the fight against racism is a universal cause and that the power of Mingus’s work artistically assists that cause, thus the creation of her moving new recording, I pledge allegiance to the flag – the white flag.

![Mammal Hands - Circadia (2026) [Hi-Res] Mammal Hands - Circadia (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771945393_folder.jpg)

![Joe Pass - Virtuoso (1974) [2025 DSD256] Joe Pass - Virtuoso (1974) [2025 DSD256]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771609997_ff.jpg)