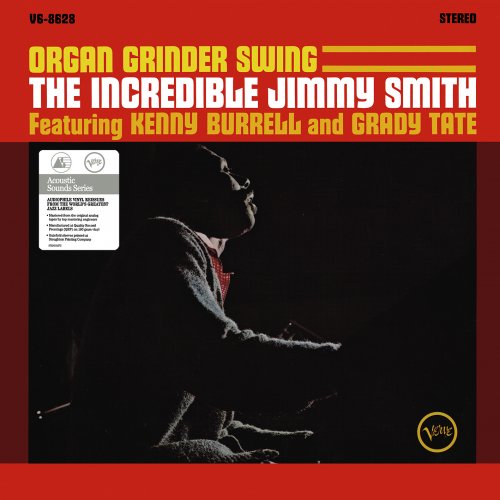

Maxim Vengerov, Mstislav Rostropovich, London Symphony Orchestra - Britten: Violin Concerto Op.15 / Walton: Viola Concerto (2003)

Artist: Maxim Vengerov, Mstislav Rostropovich, London Symphony Orchestra

Title: Britten: Violin Concerto Op.15 / Walton: Viola Concerto

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: EMI Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 64:29

Total Size: 289 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Britten: Violin Concerto Op.15 / Walton: Viola Concerto

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: EMI Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 64:29

Total Size: 289 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Benjamin Britten / Violin Concerto, Op.15 (revised version) (33:40)

1. I Moderato con moto 10:05

2. II Vivace - Cadenza 8:25

3. III Passacaglia: Andante lento (un poco meno mosso) 15:10

Sir William Walton / Viola Concerto (1961 version) (30:28)

4. I Andante comodo 9:44

5. II Vivo con moto preciso 4:21

6. III Allegro moderato 16:23

Personnel:

Viola – Maxim Vengerov

Violin – Maxim Vengerov

The London Symphony Orchestra

Conductor – Mstislav Rostropovich

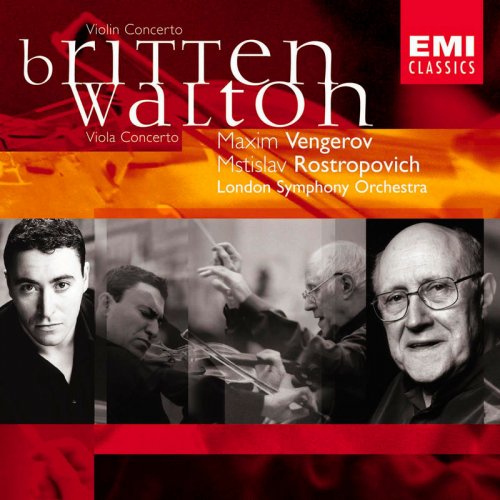

From St. James to St. Petersburg. Coming so close on the heels of Hickox and Mordkovitch's superb reading of the Britten on Chandos (CHAN 9910), this release gave me pause. Vengerov, of course, can play the violin, and Britten wrote enthusiastically for the cellist Rostropovich, so Rostropovich knows well Britten's musical neighborhood. This account holds up well, for the most part. For a very long time, listeners were more or less stuck with Britten's account with violinist Mark Lubotsky, one of the few failures in Britten's performances of his own music. Now listeners actually have a choice to make.

Mordkovitch revealed something new about the concerto. Always considered formally innovative, it nevertheless failed to connect emotionally with a great many listeners, despite the hints from its first soloist, Antonio Brosa. Hickox and Mordkovitch discovered the concerto's links to the doomed Republican side of the Spanish Civil War. In their hands, the first and last movements became a kind of elegy, separated by a bitter, acerbic scherzo. Vengerov and Rostropovich get some of that intense melancholy, without emphasizing the specifically Spanish links, as one hears in the Chandos recording. Furthermore, they disappoint structurally, particularly in the last movement. The passacaglia finale never gels as a passacaglia and never reaches the architectural coherence of Mordkovitch and Hickox.

Walton's viola concerto, definitely one of the greats for the instrument, has never really caught on like his violin concerto, judging by the number of recordings, at any rate. I have no idea whether this comes from its being a viola concerto or, because early Walton, it lacks the characteristic sound and bounce many expect from Walton's music. Like the Britten, it presents an unusual structure: a mainly slow first movement, a scherzo, and a weighty finale. In the liner notes, Malcolm MacDonald claims the Prokofiev second violin concerto as the model for both Britten and Walton. The first movement is mainly melancholy and lyrical, interspersed with vigorous bustle for contrast. The second movement, an extended rondo, fizzes along close to The Walton We Know, but not quite so jazzy. Vengerov and Rostropovich perform Walton's revision from the Sixties, which brings the work closer to his usual sound. The finale starts off with a cheeky little march on the bassoon, but soon veers off into the sweetly sad territory of the first movement. The two elements jostle one another for space, including an astonishing, glittering contrapuntal display of the march, but in the end the march theme gets reduced to tags and mere accompaniment, as the soloist recalls the slow material of the first movement. In fact, it turns out that the march and the concerto's opening theme are cousins. The viola takes up the concerto's opening in a sad benediction, full of regret. I consider this concerto one of the most sheerly beautiful for the instrument, mainly because it sings with such cool and self-possession -- a role that a violist can assume naturally.

The recording to beat for me is the EMI recording led by Walton himself, with Menuhin as soloist. It's still a great recording, but I think Rostropovich and Vengerov surpass it. They put more blood into the piece. Vengerov plays the viola like the violin superstar he is -- and it's a little surprising to hear it this way, let me tell you -- but the passion rises here more than with Menuhin, Bashmet, or Primrose. And the London Symphony Orchestra has the piece down. The fact that Vengerov and Rostropovich do so much better with the Walton than with the Britten doesn't really surprise me. The Britten is such an odd duck of a work, it's hard to grasp architecturally and emotionally. In Walton, the emotions, though deep, aren't as complicated, and the structure lies closer to more familiar pieces.

EMI's sound comes off a bit bright, but the sonic perspective and solo/tutti balance are absolutely right.

Mordkovitch revealed something new about the concerto. Always considered formally innovative, it nevertheless failed to connect emotionally with a great many listeners, despite the hints from its first soloist, Antonio Brosa. Hickox and Mordkovitch discovered the concerto's links to the doomed Republican side of the Spanish Civil War. In their hands, the first and last movements became a kind of elegy, separated by a bitter, acerbic scherzo. Vengerov and Rostropovich get some of that intense melancholy, without emphasizing the specifically Spanish links, as one hears in the Chandos recording. Furthermore, they disappoint structurally, particularly in the last movement. The passacaglia finale never gels as a passacaglia and never reaches the architectural coherence of Mordkovitch and Hickox.

Walton's viola concerto, definitely one of the greats for the instrument, has never really caught on like his violin concerto, judging by the number of recordings, at any rate. I have no idea whether this comes from its being a viola concerto or, because early Walton, it lacks the characteristic sound and bounce many expect from Walton's music. Like the Britten, it presents an unusual structure: a mainly slow first movement, a scherzo, and a weighty finale. In the liner notes, Malcolm MacDonald claims the Prokofiev second violin concerto as the model for both Britten and Walton. The first movement is mainly melancholy and lyrical, interspersed with vigorous bustle for contrast. The second movement, an extended rondo, fizzes along close to The Walton We Know, but not quite so jazzy. Vengerov and Rostropovich perform Walton's revision from the Sixties, which brings the work closer to his usual sound. The finale starts off with a cheeky little march on the bassoon, but soon veers off into the sweetly sad territory of the first movement. The two elements jostle one another for space, including an astonishing, glittering contrapuntal display of the march, but in the end the march theme gets reduced to tags and mere accompaniment, as the soloist recalls the slow material of the first movement. In fact, it turns out that the march and the concerto's opening theme are cousins. The viola takes up the concerto's opening in a sad benediction, full of regret. I consider this concerto one of the most sheerly beautiful for the instrument, mainly because it sings with such cool and self-possession -- a role that a violist can assume naturally.

The recording to beat for me is the EMI recording led by Walton himself, with Menuhin as soloist. It's still a great recording, but I think Rostropovich and Vengerov surpass it. They put more blood into the piece. Vengerov plays the viola like the violin superstar he is -- and it's a little surprising to hear it this way, let me tell you -- but the passion rises here more than with Menuhin, Bashmet, or Primrose. And the London Symphony Orchestra has the piece down. The fact that Vengerov and Rostropovich do so much better with the Walton than with the Britten doesn't really surprise me. The Britten is such an odd duck of a work, it's hard to grasp architecturally and emotionally. In Walton, the emotions, though deep, aren't as complicated, and the structure lies closer to more familiar pieces.

EMI's sound comes off a bit bright, but the sonic perspective and solo/tutti balance are absolutely right.

DOWNLOAD FROM ISRA.CLOUD

Maxim Vengerov Mstislav Rostropovich Britten Walton Concertos 03 1803.rar - 289.3 MB

Maxim Vengerov Mstislav Rostropovich Britten Walton Concertos 03 1803.rar - 289.3 MB

![Ablaye Cissoko, Kiya Tabassian, Constantinople - Estuaire (2026) [Hi-Res] Ablaye Cissoko, Kiya Tabassian, Constantinople - Estuaire (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/05/bd2ycop79dvrdm4dy879uxato.jpg)