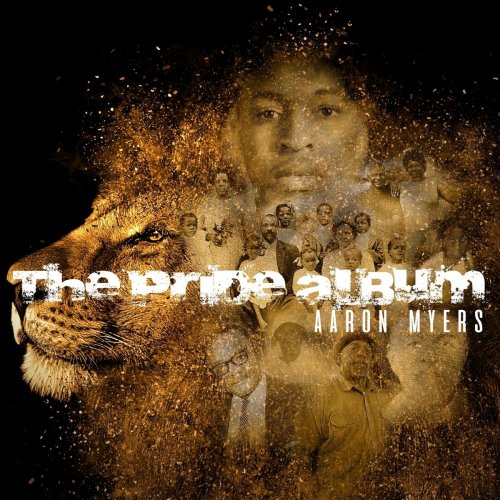

Aaron Myers - The Pride Album (2021)

Artist: Aaron Myers

Title: The Pride Album

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Aaron Myers

Genre: Jazz, Vocal Jazz, Soul

Quality: Mp3 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 56:10 min

Total Size: 136 / 359 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: The Pride Album

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Aaron Myers

Genre: Jazz, Vocal Jazz, Soul

Quality: Mp3 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 56:10 min

Total Size: 136 / 359 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Make Them Hear You

02. Down By The Riverside

03. New Jim Crow

04. How Can I

05. Moanin'

06. Don't Ask

07. Lonely

08. Return to Spain (Ode to Chick Corea)

09. If It Only Took Love

10. Let's Fall in Love

11. Please Take Care of You For Me

12. Pride

Much has been said—indeed, much of it by this writer—of Aaron Myers’s outsize persona. Let no one doubt the singer and pianist’s surplus of personality and the charisma with which he plies it. Just know, too, that it can be deceiving. In a jazz tradition (particularly strong among singers) that stretches back to Louis Armstrong, Myers is a gregarious entertainer but also an artist of great nuance and profundity. And on Pride, he’s got something nuanced and profound to say.

This album might be alternatively titled The Meeting. We’re not talking about a stuffy boardroom affair here, or even a sit-down at one of DC’s steakhouses. This is a meeting in the sense that the Black church uses the term, the meeting of King Oliver’s “Camp Meeting Blues” or Mingus’s “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting.” A blend of worship service, community forum, and social gathering. The presence of this tradition in Myers’s music can be no surprise to anyone who’s heard the southern-soul grit of his voice or his preacherly cadence.

That said, Myers doesn’t take an on-the-nose approach. This recording is not about such a meeting, per se; it (abstractly) re-creates the feeling and flow of those meetings. The meeting becomes a conduit for all of life’s experience—although in a sense that’s exactly what it’s been all along.

“Make Them Hear You,” for example, is not a literal summons to a gathering. It is, however, a call to action. Myers thinks of it as something like a church or school bell, and indeed it builds up from a fragile piano and soft voice to a real clarion call. Written by Stephen Flaherty, the song is from the musical Ragtime, where it serves as the climax; here it is the introduction, letting you know that important things are at hand.

The closest we come to addressing the meeting head-on is in “Down by the Riverside,” the Negro spiritual. It’s the processional music, arranged with a second line rhythm that adds an instrument with each new stanza. (The congregation is arriving.) It also acts as an evocation of the ancestors, who, in the African tradition, are asked for permission to speak as the meeting begins. Myers takes it on with a combination of joy and earnestness.

Myers’s original composition “The New Jim Crow” takes its title from Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Knowing that, the title almost speaks for itself. The lyrics, too, cut right to the point. Yet it’s the musicians that create the song’s sharp urgency, both in Myers’s vocal delivery and in the chaotic but moving free-improvisation section at the track’s center.

The pressing issue has been raised; now, “How Can I?” offers testimony. It’s another Myers original, and it takes the shape of a powerful soliloquy. The lyrics seek cosmic (perhaps) answers. It swells into a magnificent catharsis, with Myers and his partner-in-crime, alto saxophonist Herb Scott, breaking into a soulful call and response at its climax.

On “Moanin’,” cathartic release comes at the beginning, with a roiling introduction by Myers, Scott, Funn, pianist Sam Prather, and drummer Dana Hawkins. The Bobby Timmons classic, often a centerpiece of Myers’s live performances, is a hard-hitting performance that is drenched in the blues and the church. Think of it as a group response to the “How Can I?” testimony, an outpouring of anger and grief and worry that, in its closing moments, lists its troubles (and its victims) by name. Those of us in Myers’s home of Washington, DC, in 2021 know that his mention of the Proud Boys is not some distant abstract.

“Don’t Ask Me to Smile” really is self-explanatory. “Don’t ask me to smile when you oppress me,” Myers sings, with his heart on his sleeve. “Don’t ask me to smile, just set me free….I cannot smile, I am not at peace.” Scott follows with a heart-rending solo. If the bridge of the song reminds you of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” that’s no coincidence. It’s meant as something of a rejoinder to the classic standard: There is no faraway paradise where troubles melt like lemon drops, there is only the here and now and all the weight it bears.

That weight compounds itself on “Lonely,” a stunning composition cowritten by Myers and Funn. It takes us momentarily out of the meeting, by way of a moment of silent prayer: Even in the midst of a gathering, we are left alone with our thoughts and whatever spirit we might be communing with. Yet loneliness is also a pandemic of its own, touching all of us in this era of COVID-19 (and many of us before and afterward, where circumstances make it so). And all of us will experience a relapse somewhere down the line.

Yet it’s always darkest before the dawn, as they say, and with “Return to Spain,” light begins to break through. Certainly “bright” is a good word for the Myers instrumental. It’s inspired by the late Chick Corea’s theme song but also packed with the rhythms and harmonic accents of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora—what Jelly Roll Morton called jazz’s “Spanish tinge.” Then there’s the rhythms of Dana Hawkins, whose drum solo fires on all cylinders.

Our meeting turns its discussion from tragedy to love, although there’s plenty of tragedy to be found there too. “If It Only Took Love” gives us both the dizzying highs and the devastating lows, the bitter and the sweet. It’s also a beautiful example of Myers’s dynamic performance style, a counterpoint to the fierce belting of “Moanin’” that’s all about subtlety, delicacy, and a painter’s attention to detail.

Those attributes—as well as a real emotional crescendo—become even more acute on “Let’s Fall in Love.” Love’s agony is offset by its ecstasy, when not overwhelmed by it. Missing from the title is the word “again,” which might be the key—even with the pain of “If It Only Took Love,” we are ready, even desperate, to dive into those waters again. Maybe we’re even ready to fall in love again with the person for whom we know love was not enough.

“Please Take Care of You for Me” has the feel of the ‘70s singer/songwriters, particularly the African American exponents like Roberta Flack and Bill Withers. (The acoustic guitar—courtesy of Steve Arnold—Fender Rhodes, and mellow groove have something to do with that feel.) It’s also got a remarkable tenderness to it. These are words spoken by and to people who are fond of each other, who care. Again it evokes the pandemic: Who among us hasn’t said this lately to our loved ones?

They are also sentiments of farewell. The meeting is breaking up, but not before reminding its participants of what’s important. “Pride” refers both to the dignity and self-assurance that can be renewed through gathering together, but to the gathering itself: “pride” is the word for a lion’s family, its community. When Myers sings “I’ve got my pride” with such assurance, he means the word in every sense of the term. Appropriately, his pride expands here with a vocal chorus that includes Akua Allrich, Deborah Bond, Cash J, and Earl Lloyd.

As of this writing, many of the events described in Myers’s songs are recent, even ongoing. Yet their effects and the emotions that accompany them are universal ones, for better and for worse. If you’re listening to Pride in 2021, 2071, or 3021, something in it will still speak to you. That’s the kind of artist that Aaron Myers is.

Michael J. West is a jazz journalist in Washington, DC.

This album might be alternatively titled The Meeting. We’re not talking about a stuffy boardroom affair here, or even a sit-down at one of DC’s steakhouses. This is a meeting in the sense that the Black church uses the term, the meeting of King Oliver’s “Camp Meeting Blues” or Mingus’s “Wednesday Night Prayer Meeting.” A blend of worship service, community forum, and social gathering. The presence of this tradition in Myers’s music can be no surprise to anyone who’s heard the southern-soul grit of his voice or his preacherly cadence.

That said, Myers doesn’t take an on-the-nose approach. This recording is not about such a meeting, per se; it (abstractly) re-creates the feeling and flow of those meetings. The meeting becomes a conduit for all of life’s experience—although in a sense that’s exactly what it’s been all along.

“Make Them Hear You,” for example, is not a literal summons to a gathering. It is, however, a call to action. Myers thinks of it as something like a church or school bell, and indeed it builds up from a fragile piano and soft voice to a real clarion call. Written by Stephen Flaherty, the song is from the musical Ragtime, where it serves as the climax; here it is the introduction, letting you know that important things are at hand.

The closest we come to addressing the meeting head-on is in “Down by the Riverside,” the Negro spiritual. It’s the processional music, arranged with a second line rhythm that adds an instrument with each new stanza. (The congregation is arriving.) It also acts as an evocation of the ancestors, who, in the African tradition, are asked for permission to speak as the meeting begins. Myers takes it on with a combination of joy and earnestness.

Myers’s original composition “The New Jim Crow” takes its title from Michelle Alexander’s book The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. Knowing that, the title almost speaks for itself. The lyrics, too, cut right to the point. Yet it’s the musicians that create the song’s sharp urgency, both in Myers’s vocal delivery and in the chaotic but moving free-improvisation section at the track’s center.

The pressing issue has been raised; now, “How Can I?” offers testimony. It’s another Myers original, and it takes the shape of a powerful soliloquy. The lyrics seek cosmic (perhaps) answers. It swells into a magnificent catharsis, with Myers and his partner-in-crime, alto saxophonist Herb Scott, breaking into a soulful call and response at its climax.

On “Moanin’,” cathartic release comes at the beginning, with a roiling introduction by Myers, Scott, Funn, pianist Sam Prather, and drummer Dana Hawkins. The Bobby Timmons classic, often a centerpiece of Myers’s live performances, is a hard-hitting performance that is drenched in the blues and the church. Think of it as a group response to the “How Can I?” testimony, an outpouring of anger and grief and worry that, in its closing moments, lists its troubles (and its victims) by name. Those of us in Myers’s home of Washington, DC, in 2021 know that his mention of the Proud Boys is not some distant abstract.

“Don’t Ask Me to Smile” really is self-explanatory. “Don’t ask me to smile when you oppress me,” Myers sings, with his heart on his sleeve. “Don’t ask me to smile, just set me free….I cannot smile, I am not at peace.” Scott follows with a heart-rending solo. If the bridge of the song reminds you of “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” that’s no coincidence. It’s meant as something of a rejoinder to the classic standard: There is no faraway paradise where troubles melt like lemon drops, there is only the here and now and all the weight it bears.

That weight compounds itself on “Lonely,” a stunning composition cowritten by Myers and Funn. It takes us momentarily out of the meeting, by way of a moment of silent prayer: Even in the midst of a gathering, we are left alone with our thoughts and whatever spirit we might be communing with. Yet loneliness is also a pandemic of its own, touching all of us in this era of COVID-19 (and many of us before and afterward, where circumstances make it so). And all of us will experience a relapse somewhere down the line.

Yet it’s always darkest before the dawn, as they say, and with “Return to Spain,” light begins to break through. Certainly “bright” is a good word for the Myers instrumental. It’s inspired by the late Chick Corea’s theme song but also packed with the rhythms and harmonic accents of the Afro-Caribbean diaspora—what Jelly Roll Morton called jazz’s “Spanish tinge.” Then there’s the rhythms of Dana Hawkins, whose drum solo fires on all cylinders.

Our meeting turns its discussion from tragedy to love, although there’s plenty of tragedy to be found there too. “If It Only Took Love” gives us both the dizzying highs and the devastating lows, the bitter and the sweet. It’s also a beautiful example of Myers’s dynamic performance style, a counterpoint to the fierce belting of “Moanin’” that’s all about subtlety, delicacy, and a painter’s attention to detail.

Those attributes—as well as a real emotional crescendo—become even more acute on “Let’s Fall in Love.” Love’s agony is offset by its ecstasy, when not overwhelmed by it. Missing from the title is the word “again,” which might be the key—even with the pain of “If It Only Took Love,” we are ready, even desperate, to dive into those waters again. Maybe we’re even ready to fall in love again with the person for whom we know love was not enough.

“Please Take Care of You for Me” has the feel of the ‘70s singer/songwriters, particularly the African American exponents like Roberta Flack and Bill Withers. (The acoustic guitar—courtesy of Steve Arnold—Fender Rhodes, and mellow groove have something to do with that feel.) It’s also got a remarkable tenderness to it. These are words spoken by and to people who are fond of each other, who care. Again it evokes the pandemic: Who among us hasn’t said this lately to our loved ones?

They are also sentiments of farewell. The meeting is breaking up, but not before reminding its participants of what’s important. “Pride” refers both to the dignity and self-assurance that can be renewed through gathering together, but to the gathering itself: “pride” is the word for a lion’s family, its community. When Myers sings “I’ve got my pride” with such assurance, he means the word in every sense of the term. Appropriately, his pride expands here with a vocal chorus that includes Akua Allrich, Deborah Bond, Cash J, and Earl Lloyd.

As of this writing, many of the events described in Myers’s songs are recent, even ongoing. Yet their effects and the emotions that accompany them are universal ones, for better and for worse. If you’re listening to Pride in 2021, 2071, or 3021, something in it will still speak to you. That’s the kind of artist that Aaron Myers is.

Michael J. West is a jazz journalist in Washington, DC.

![VA - Wamono Disco: Nippon Columbia Disco & Boogie Hits 1978-1982 (2024) [Viny] VA - Wamono Disco: Nippon Columbia Disco & Boogie Hits 1978-1982 (2024) [Viny]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-03/1772454355_cover.jpg)