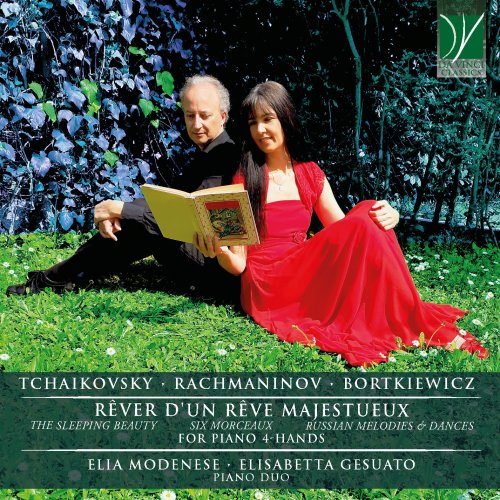

Elia Modenese & Elisabetta Gesuato - Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Bortkiewicz: Rêver d'un rêve majestueux (2021)

- 09 Jul, 08:06

- change text size:

Facebook

Twitter

Artist: Elia Modenese, Elisabetta Gesuato

Title: Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Bortkiewicz: Rêver d'un rêve majestueux (For Piano 4-Hands)

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 1:01:30

Total Size: 207 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninov, Bortkiewicz: Rêver d'un rêve majestueux (For Piano 4-Hands)

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 1:01:30

Total Size: 207 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. The Sleeping Beauty, Op. 66a: I. Introduction [Prologue, Introduction and No. 4] (Arranged by Sergej Rachmaninov)

02. The Sleeping Beauty, Op. 66a: II. Adagio [Act 1, No. 8a] (Arranged by Sergej Rachmaninov)

03. The Sleeping Beauty, Op. 66a: III. Pas de caractère [Act 3, No. 24] (Arranged by Sergej Rachmaninov)

04. The Sleeping Beauty, Op. 66a: IV. Panorama [Act 2, No. 17] (Arranged by Sergej Rachmaninov)

05. The Sleeping Beauty, Op. 66a: V. Waltz [Act 1, No. 6] (Arranged by Sergej Rachmaninov)

06. 6 Morceaux, Op. 11: No. 1 in G Minor, Barcarolle, Moderato

07. 6 Morceaux, Op. 11: No. 2 in D Major, Scherzo, Allegro

08. 6 Morceaux, Op. 11: No. 3 in B Minor, Thème russe, Andantino cantabile

09. 6 Morceaux, Op. 11: No. 4 in A Major, Valse, Tempo di Valse

10. 6 Morceaux, Op. 11: No. 5 in C Minor, Romance, Andante con anima

11. 6 Morceaux, Op. 11: No. 6 in C Major, Glory, Allegro moderato

12. Russian Melodies & Dances, Op. 31: I. Molto sostenuto e tranquillo

13. Russian Melodies & Dances, Op. 31: II. Allegro vivace

14. Russian Melodies & Dances, Op. 31: III. Allegro non tanto

15. Russian Melodies & Dances, Op. 31: IV. Andantino

16. Russian Melodies & Dances, Op. 31: V. Allegretto

17. Russian Melodies & Dances, Op. 31: VI. Allegro con brio

It is a happy day for the Tchaikovsky household. We are in 1867, and the entire family is gathered in their summer residence. A private show is being prepared: one of Charles Perrault’s best known fairy tales, Sleeping Beauty, is being staged. Family members narrate that the composer had written the score for a home performance, in which the children were to act. The creation of Swan Lake had also had a similar genesis. Thus, the main musical themes of both works had been crafted almost playfully, for the purpose of entertaining the family. Twenty-one years later, in 1888, Prince Vselovosky (the Superintendent of the Imperial Theatres) asked Tchaikovsky to write the score for Sleeping Beauty, choreographed by Marius Petipa, the famous French choreographer, and to be staged at St. Petersburg’s Marijnsky Theatre. In 1877, Swan Lake had been performed at Moscow’s Bolshoi Theatre. Its success had not been immediate. The critics had not appreciated the exceedingly “symphonic” style of the composer. They had noted a compositional complexity different from the stereotypes employed by court composers. This new production, then, represented for Tchaikovsky a new opportunity for affirming his style and his aesthetic ideas. Indeed, the Prince had wanted Tchaikovsky to be at his side, precisely with the purpose of bringing some fresh air to the Russian Imperial ballet.

The Prince had written the story’s libretto together with Petipa, and he had designed the sketches for sumptuous costumes in the majestic fashion of the court of the “Sun King”. He had employed no less than five scenographers for creating the scenes; they had been instructed to take inspiration from the famous drawings by illustrator Gustave Doré.

The work’s staging costed a fourth of the Imperial Theatres’ annual budget; the dress rehearsal, on January 14th, 1890, was performed in the presence of the Czar, Alexander III Romanov, and of his Court.

The ballet’s success kept increasing, and it reached 50 performances. The role of Aurora, the protagonist, was entrusted to the Italian ballerina Carlotta Brianza; six years later, she would dance it again in the ballet’s European premiere, in Italy, at the La Scala Theatre in Milan.

The artistic fellowship between composer and choreographer produced yet another undisputed masterpiece, The Nutcracker, in 1892. It all came to an abrupt end in the following year, when the composer died in St Petersburg. However, the heritage of his trilogy (Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker) was to change the world of dance forever.

Ballet was, by now, on a par with the great operatic productions. It was a complex and complete artistic show, with staging, melodramatic plots, recitation and acting. Music was no longer intended as a mere accompaniment to the dancers’ choreographies, but rather as a complex score, whose orchestral component possessed the dignity of an autonomous work. For this reason, Tchaikovsky also created orchestral suites out of his ballets; they would obtain great success in the concert programmes. Moreover, for the purpose of disseminating the works and for theatrical rehearsals, piano arrangements were produced as well.

It seems certain that the four-hand piano duet version of Sleeping Beauty was commissioned by Tchaikovsky himself to Sergej Rachmaninov, who, at that time, was still a young student. The solo piano version was made by a pianist, Aleksander Ziloti, who was a cousin of Rachmaninov and who had studied harmony at the Moscow Conservatory under Tchaikovsky’s guidance and who, at that time, was contributing to establishing young Rachmaninov’s fame.

The four-hand version of the Suites from Swan Lake and Nutcracker was entrusted to Eduard Langer: this arrangement is still commonly found in today’s repertoires of many piano duos.

The orchestral Suite summarises, in the space of twenty minutes, one of the longest ballets in history: it amounts to almost three hours of music (originally, they were four!), structured in a Prologue and three Acts, for a total of circa 22 scenes. In the Suite, Tchaikovsky included five pieces representing the musical themes which were most cherished by the audience for their musicality and immediacy, regardless of the plot’s chronological development, but rather privileging an aesthetically balanced juxtaposition. The orchestral Suite was faithfully arranged by Rachmaninov for four-hand piano duet; however, he impressed to the piece a virtuosic shape, with a rich harmonic texture and complexity in the intertwining of the two performers’ parts, following his unmistakable style.

The Suite begins with a Prologue, representing the eternal struggle between good and evil. Two contrasting musical themes embody the two fairies who initiate the story’s action. The first theme, agitated and disquieting, represents fairy Carabosse, who had not been invited to Princess Aurora’s baptism. Wishing to take revenge, she pronounces a curse: at her sixteenth birthday, Aurora will die after pricking one of her fingers. Good Lilac Fairy intervenes with an enchantment: Aurora will not die, but rather fall asleep until a love-kiss will awake her. The lyrical theme of Lilac Fairy, which is hinted at in the Prologue, is cited entirely at the end of Act One and united here to the Prologue itself. Tchaikovsky’s music narrates the prophecy’s accomplishment. Aurora is celebrating her sixteenth birthday with a great courtly festivity. Having received a bunch of flowers as a gift from Carabosse, dressed up as an old beggar, she pricks her finger with a spindle hidden among the flowers, and falls to the floor, losing consciousness. Lilac Fairy acts immediately, in the midst of the numerous guests’ despair. With her wand, she puts to sleep Aurora and the entire court. This action is underpinned by a tremolo and by a series of quick sextuplets, enfolding the unmistakable and sweet theme of the Fairy. Rachmaninov himself indicates, on the score, the passages in which music recounts the various stages of the action.

The castle falls deeply asleep for a hundred years, waiting for him who will be able to feel such a pure and deep love in his heart so as to make the curse vanish.

As in a flashback, the second piece of the Suite, by the name of Adagio. Pas d’action, describes an earlier scene, excerpted from the beginning of Act One. Aurora is happily dancing at her birthday feast, ignoring what will happen to her. Her father had invited four princes, heirs to the throne of faraway kingdoms, in order for his daughter to choose her husband-to-be. She dances the famous Rose Adagio with each one of them. Celebratory, almost triumphal court dances follow; nobody can imagine what will happen soon.

The story is left open: the Suite’s third piece, excerpted from the last Act, is a valuable miniature, inserted as a homage to Perrault’s genius. It is the pas de charactère of the Puss in Boots, who attempts to conquer the beautiful White Cat.

Among the numerous guests at the wedding feast of Aurora and Prince Désiré, before the grand finale, many fairy-tale characters of Perrault’s stories dance. Among them Puss in Boots with the White Cat, Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf, Princess Florine with the Bluebird, Cinderella and Prince Charming.

Tchaikovsky’s music underpins the feline gestures of the couple, which alternates flatteries and minor fights. It is a love duet, in which the two cats’ playfulness, seduction and love’s labours ironically stage a couple’s relationship.

With the fourth piece, titled “Panorama” (the last scene of Act Two) we get back to the plot’s narrative. After a hundred years, Lilac Fairy finally finds a youth capable of melting, by his love, Carabosse’s curse. The Prince is in the forest after a hunting party; he is melancholic and lonely. Lilac Fairy appears to him, evoking Aurora’s portrait. The Prince falls in love with the image, and he decides to follow the fairy, who will lead him, thanks to an enchanted ship, to Aurora’s castle. Music describes this journey, filled with dreams and expectations, which will guide the Prince from loneliness to love.

The Suite closes with the famous Waltz of Act One, the waltz of Aurora’s birthday feast. The music expresses the young girl’s dreams; she is open to life, awaiting her true love. Just after the waltz, in fact, the Princess will dance with the four Princes who had been invited to the party by her father (see the Suite’s second piece); however, she would not feel the full power of that sentiment for any one of them. The Prince’s dreams, depicted in the preceding piece (“Panorama”) thus intertwine with her own dreams, represented by this sparkling waltz, filled with the expectations for her future life.

Thus the Suite closes: not with the music of the final scene, that of Aurora’s nuptials, but rather with the waltz depicting her imagination and dream of her future of love.

A few years after transcribing Sleeping Beauty, Rachmaninov composed his own Six Morceaux op. 11 for four-hand piano duet. We are in 1894; the composer had just finished his musical studies, obtaining a degree from the Moscow Conservatory. Rachmaninov felt himself to be the heir of a tradition, symbolized by the late-nineteenth-century, “Western” melodic style. This was embodied by Tchaikovsky (to whom Rachmaninov had dedicated some of his works) and by the Russian national school of Glinka, Mussorgsky, Balakirev and Rimsky-Korsakov. These two souls of his land coexisted in him.

In the Six Morceaux op. 11 we find echoes from both traditions. The suite is opened by a Barcarole, with a Chopinesque inspiration. Tradition entrusts this genre with a descriptive intention, evoking images and atmospheres of the Venetian laguna, whose channels are populated with gondolieri. Powerful chords animate the theme, sustained by an undulating and syncopated rhythm. We should not forget that Rachmaninov, as a child, had received his first piano lessons from his mother, and also from his paternal grandfather. The latter had been a pupil of John Field, i.e. the composer who wrote the first Nocturnes, those which would inspire Chopin.

Reminiscences of Chopin’s famous waltzes are found in the fourth piece, Valse. The composer reinterprets this musical genre in a personal key, intertwining different themes and technical passageworks detached from the melodic line.

Also the following piece, Romance, is almost a lyrical and melodic nocturne, reinterpreted by Rachmaninov in a passionate and almost tortured form. The other three pieces in the collection are clearly marked by a Russian folklike and popular style.

The Scherzo, with a brilliant and virtuosic character, offers to the listener an abundance of rhythmical ideas, charged with irony. Thema begins with the motif of a popular song, structured upon the intervals of the modal scale typical for folklike themes. It sweetly recounts about long winters and icy steppes. The theme becomes animated, and turns into a lively dance, accelerating in accord with the tradition of popular group dances. Slava concludes the work, proposing the theme of an Orthodox liturgical chant, used also by Mussorgsky in his opera Boris Godunov. The mass of chords following each other remind us of the last piece of Pictures at an Exhibition, describing the majestic Gate of Kiev.

The Russia of folklore, of the Cossacks’ acrobatic dances and of the sad and meditative songs of popular tradition are echoed more pronouncedly in the collection Russian Melodies and Dances op. 31 by Bortkiewicz. The composer was born in Ukraine in 1877, just four years apart from Rachmaninov. He studied at the St Petersburg Conservatory and later moved to Leipzig, where he completed his education with two of Liszt’s favourite pupils. After First World War, he finally settled in Vienna. Bortkiewicz’s work cites the structure of Rachmaninov’s Six Morceaux. Here too six pieces follow each other, characterized by slow and singing themes which become animated through sudden changes of pace. We find crescendos ending up as dizzying Cossack dances, or as masses of celebrative chords, reminiscent of the patriotic music at the Imperial Court.

In both works we find a waltz, developing itself sweetly on Russian and Slavic themes.

Bortkiewicz’s works opens with a homage to Tchaikovsky, the unsurpassed model and capstone of the Russian tradition. The first piece is built on a folk theme, excerpted from Opricnik, an opera by the great master. This sweet theme, in Tchaikovsky’s opera, was sung by a female choir. Bortkiewicz transforms this theme until it becomes imperial and grandioso; then he changes it once more, up to the final disappearance.

Three works by three composers intertwine in this album for four-hand piano duet. This ensemble was chosen by these composers in order to realize the complex harmonic texture and melodic beauty of the great Russian tradition.

The Prince had written the story’s libretto together with Petipa, and he had designed the sketches for sumptuous costumes in the majestic fashion of the court of the “Sun King”. He had employed no less than five scenographers for creating the scenes; they had been instructed to take inspiration from the famous drawings by illustrator Gustave Doré.

The work’s staging costed a fourth of the Imperial Theatres’ annual budget; the dress rehearsal, on January 14th, 1890, was performed in the presence of the Czar, Alexander III Romanov, and of his Court.

The ballet’s success kept increasing, and it reached 50 performances. The role of Aurora, the protagonist, was entrusted to the Italian ballerina Carlotta Brianza; six years later, she would dance it again in the ballet’s European premiere, in Italy, at the La Scala Theatre in Milan.

The artistic fellowship between composer and choreographer produced yet another undisputed masterpiece, The Nutcracker, in 1892. It all came to an abrupt end in the following year, when the composer died in St Petersburg. However, the heritage of his trilogy (Swan Lake, Sleeping Beauty and The Nutcracker) was to change the world of dance forever.

Ballet was, by now, on a par with the great operatic productions. It was a complex and complete artistic show, with staging, melodramatic plots, recitation and acting. Music was no longer intended as a mere accompaniment to the dancers’ choreographies, but rather as a complex score, whose orchestral component possessed the dignity of an autonomous work. For this reason, Tchaikovsky also created orchestral suites out of his ballets; they would obtain great success in the concert programmes. Moreover, for the purpose of disseminating the works and for theatrical rehearsals, piano arrangements were produced as well.

It seems certain that the four-hand piano duet version of Sleeping Beauty was commissioned by Tchaikovsky himself to Sergej Rachmaninov, who, at that time, was still a young student. The solo piano version was made by a pianist, Aleksander Ziloti, who was a cousin of Rachmaninov and who had studied harmony at the Moscow Conservatory under Tchaikovsky’s guidance and who, at that time, was contributing to establishing young Rachmaninov’s fame.

The four-hand version of the Suites from Swan Lake and Nutcracker was entrusted to Eduard Langer: this arrangement is still commonly found in today’s repertoires of many piano duos.

The orchestral Suite summarises, in the space of twenty minutes, one of the longest ballets in history: it amounts to almost three hours of music (originally, they were four!), structured in a Prologue and three Acts, for a total of circa 22 scenes. In the Suite, Tchaikovsky included five pieces representing the musical themes which were most cherished by the audience for their musicality and immediacy, regardless of the plot’s chronological development, but rather privileging an aesthetically balanced juxtaposition. The orchestral Suite was faithfully arranged by Rachmaninov for four-hand piano duet; however, he impressed to the piece a virtuosic shape, with a rich harmonic texture and complexity in the intertwining of the two performers’ parts, following his unmistakable style.

The Suite begins with a Prologue, representing the eternal struggle between good and evil. Two contrasting musical themes embody the two fairies who initiate the story’s action. The first theme, agitated and disquieting, represents fairy Carabosse, who had not been invited to Princess Aurora’s baptism. Wishing to take revenge, she pronounces a curse: at her sixteenth birthday, Aurora will die after pricking one of her fingers. Good Lilac Fairy intervenes with an enchantment: Aurora will not die, but rather fall asleep until a love-kiss will awake her. The lyrical theme of Lilac Fairy, which is hinted at in the Prologue, is cited entirely at the end of Act One and united here to the Prologue itself. Tchaikovsky’s music narrates the prophecy’s accomplishment. Aurora is celebrating her sixteenth birthday with a great courtly festivity. Having received a bunch of flowers as a gift from Carabosse, dressed up as an old beggar, she pricks her finger with a spindle hidden among the flowers, and falls to the floor, losing consciousness. Lilac Fairy acts immediately, in the midst of the numerous guests’ despair. With her wand, she puts to sleep Aurora and the entire court. This action is underpinned by a tremolo and by a series of quick sextuplets, enfolding the unmistakable and sweet theme of the Fairy. Rachmaninov himself indicates, on the score, the passages in which music recounts the various stages of the action.

The castle falls deeply asleep for a hundred years, waiting for him who will be able to feel such a pure and deep love in his heart so as to make the curse vanish.

As in a flashback, the second piece of the Suite, by the name of Adagio. Pas d’action, describes an earlier scene, excerpted from the beginning of Act One. Aurora is happily dancing at her birthday feast, ignoring what will happen to her. Her father had invited four princes, heirs to the throne of faraway kingdoms, in order for his daughter to choose her husband-to-be. She dances the famous Rose Adagio with each one of them. Celebratory, almost triumphal court dances follow; nobody can imagine what will happen soon.

The story is left open: the Suite’s third piece, excerpted from the last Act, is a valuable miniature, inserted as a homage to Perrault’s genius. It is the pas de charactère of the Puss in Boots, who attempts to conquer the beautiful White Cat.

Among the numerous guests at the wedding feast of Aurora and Prince Désiré, before the grand finale, many fairy-tale characters of Perrault’s stories dance. Among them Puss in Boots with the White Cat, Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf, Princess Florine with the Bluebird, Cinderella and Prince Charming.

Tchaikovsky’s music underpins the feline gestures of the couple, which alternates flatteries and minor fights. It is a love duet, in which the two cats’ playfulness, seduction and love’s labours ironically stage a couple’s relationship.

With the fourth piece, titled “Panorama” (the last scene of Act Two) we get back to the plot’s narrative. After a hundred years, Lilac Fairy finally finds a youth capable of melting, by his love, Carabosse’s curse. The Prince is in the forest after a hunting party; he is melancholic and lonely. Lilac Fairy appears to him, evoking Aurora’s portrait. The Prince falls in love with the image, and he decides to follow the fairy, who will lead him, thanks to an enchanted ship, to Aurora’s castle. Music describes this journey, filled with dreams and expectations, which will guide the Prince from loneliness to love.

The Suite closes with the famous Waltz of Act One, the waltz of Aurora’s birthday feast. The music expresses the young girl’s dreams; she is open to life, awaiting her true love. Just after the waltz, in fact, the Princess will dance with the four Princes who had been invited to the party by her father (see the Suite’s second piece); however, she would not feel the full power of that sentiment for any one of them. The Prince’s dreams, depicted in the preceding piece (“Panorama”) thus intertwine with her own dreams, represented by this sparkling waltz, filled with the expectations for her future life.

Thus the Suite closes: not with the music of the final scene, that of Aurora’s nuptials, but rather with the waltz depicting her imagination and dream of her future of love.

A few years after transcribing Sleeping Beauty, Rachmaninov composed his own Six Morceaux op. 11 for four-hand piano duet. We are in 1894; the composer had just finished his musical studies, obtaining a degree from the Moscow Conservatory. Rachmaninov felt himself to be the heir of a tradition, symbolized by the late-nineteenth-century, “Western” melodic style. This was embodied by Tchaikovsky (to whom Rachmaninov had dedicated some of his works) and by the Russian national school of Glinka, Mussorgsky, Balakirev and Rimsky-Korsakov. These two souls of his land coexisted in him.

In the Six Morceaux op. 11 we find echoes from both traditions. The suite is opened by a Barcarole, with a Chopinesque inspiration. Tradition entrusts this genre with a descriptive intention, evoking images and atmospheres of the Venetian laguna, whose channels are populated with gondolieri. Powerful chords animate the theme, sustained by an undulating and syncopated rhythm. We should not forget that Rachmaninov, as a child, had received his first piano lessons from his mother, and also from his paternal grandfather. The latter had been a pupil of John Field, i.e. the composer who wrote the first Nocturnes, those which would inspire Chopin.

Reminiscences of Chopin’s famous waltzes are found in the fourth piece, Valse. The composer reinterprets this musical genre in a personal key, intertwining different themes and technical passageworks detached from the melodic line.

Also the following piece, Romance, is almost a lyrical and melodic nocturne, reinterpreted by Rachmaninov in a passionate and almost tortured form. The other three pieces in the collection are clearly marked by a Russian folklike and popular style.

The Scherzo, with a brilliant and virtuosic character, offers to the listener an abundance of rhythmical ideas, charged with irony. Thema begins with the motif of a popular song, structured upon the intervals of the modal scale typical for folklike themes. It sweetly recounts about long winters and icy steppes. The theme becomes animated, and turns into a lively dance, accelerating in accord with the tradition of popular group dances. Slava concludes the work, proposing the theme of an Orthodox liturgical chant, used also by Mussorgsky in his opera Boris Godunov. The mass of chords following each other remind us of the last piece of Pictures at an Exhibition, describing the majestic Gate of Kiev.

The Russia of folklore, of the Cossacks’ acrobatic dances and of the sad and meditative songs of popular tradition are echoed more pronouncedly in the collection Russian Melodies and Dances op. 31 by Bortkiewicz. The composer was born in Ukraine in 1877, just four years apart from Rachmaninov. He studied at the St Petersburg Conservatory and later moved to Leipzig, where he completed his education with two of Liszt’s favourite pupils. After First World War, he finally settled in Vienna. Bortkiewicz’s work cites the structure of Rachmaninov’s Six Morceaux. Here too six pieces follow each other, characterized by slow and singing themes which become animated through sudden changes of pace. We find crescendos ending up as dizzying Cossack dances, or as masses of celebrative chords, reminiscent of the patriotic music at the Imperial Court.

In both works we find a waltz, developing itself sweetly on Russian and Slavic themes.

Bortkiewicz’s works opens with a homage to Tchaikovsky, the unsurpassed model and capstone of the Russian tradition. The first piece is built on a folk theme, excerpted from Opricnik, an opera by the great master. This sweet theme, in Tchaikovsky’s opera, was sung by a female choir. Bortkiewicz transforms this theme until it becomes imperial and grandioso; then he changes it once more, up to the final disappearance.

Three works by three composers intertwine in this album for four-hand piano duet. This ensemble was chosen by these composers in order to realize the complex harmonic texture and melodic beauty of the great Russian tradition.

![Cannonball Adderley - Somethin' Else (1958) [2022 DSD256] Cannonball Adderley - Somethin' Else (1958) [2022 DSD256]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770877615_folder.jpg)

![Laura Anglade - Get Out of Town (Deluxe) (2026) [Hi-Res] Laura Anglade - Get Out of Town (Deluxe) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770950244_kznexew2l78jj_600.jpg)

![Martin Fabricius Trio - Under the Same Sky (2018) [Hi-Res] Martin Fabricius Trio - Under the Same Sky (2018) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771153226_cover.jpg)