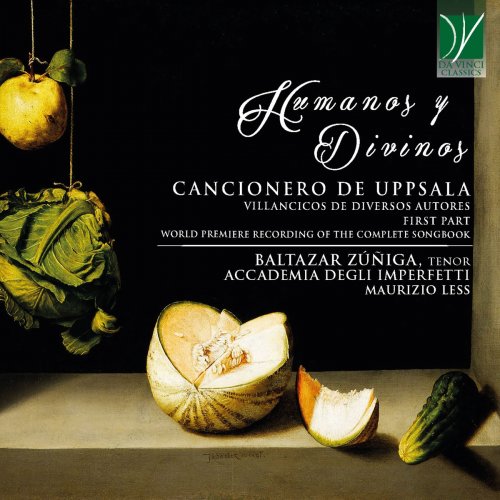

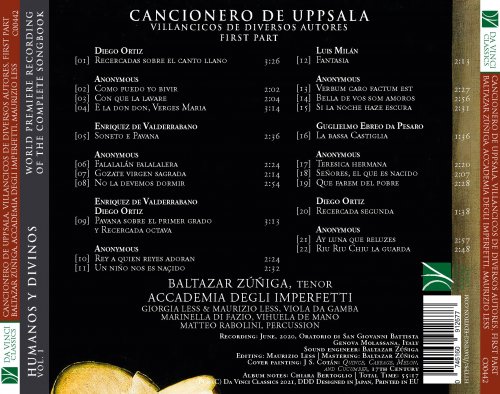

Baltazar Zuniga - Humanos y Divinos: Cancionero de Uppsala, Villancicos de Diversos Autores - First Part (2021)

Artist: Baltazar Zuniga

Title: Humanos y Divinos: Cancionero de Uppsala, Villancicos de Diversos Autores - First Part

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 55:04 min

Total Size: 273 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Title: Humanos y Divinos: Cancionero de Uppsala, Villancicos de Diversos Autores - First Part

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 55:04 min

Total Size: 273 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:

01. Recercadas sobre el canto llano

02. Como puedo yo bivir

03. Con que la lavare

04. E la don don, Verges Maria

05. Soneto e Pavana

06. Falalalán falalalera

07. Gozate virgen sagrada

08. No la devemos dormir

09. Pavana sobre el primer grado y Recercada octava

10. Rey a quien reyes adoran

11. Un niño nos es naçido

12. Fantasia

13. Verbum caro factum est

14. Bella de vos som amoros

15. Si la noche haze escura

16. La bassa Castiglia

17. Teresica hermana

18. Señores, el que es nacido

19. Que farem del pobre

20. Recercada segunda

21. Ay luna que reluzes

22. Riu Riu Chiu la guarda

Sweden is one of the northernmost European countries; Calabria is the southernmost region of the Italian peninsula. This geographic axis, crossing the entire European continent, is just one of the geographical references of the songbook constituting the object of this Da Vinci Classics recording.

While the reception history of this songbook is well documented and fascinating, very little is known about its origins, opening the gates for speculations and musicological debate. The history of its reception officially begins in 1909, with an article published by Rafael Mitjana Gordon (1869-1921). Mitjana was the Secretary to the Spanish Embassy in Stockholm, Sweden. During his stay in the Scandinavian country, in 1907, Mitjana took the opportunity of studying the holdings of an august library, in one of the oldest Universities of Europe, the University of Uppsala. In the Library known as Carolina Rediviva, his interest was caught by a relatively small book. It was a printed copy of a Venetian publication of the sixteenth century, realized by one of the most important music publishers of the era, i.e. Girolamo Scotto. The book’s complete title is “Villancicos de diversos Autores, a dos, y a tres, y a quatro, y a cinco bozes, agora nuevamente corregidos. Hay mas ocho tonos de Canto llano, y ocho tonos de Canto de Organo para que puedan aprovechar los que a cantar començaren. Venetiis, Apud Hieronymum Scotum, MDLVI”, and it actually provides us with the most detailed and reliable information we have about it.

In fact, and in an entirely unusual fashion for its time, the songbook has no dedication or preface, thus making it difficult to reconstruct the occasion or destination for which it was conceived. It is unusual also for many other reasons: it small size (209 x 147 mm), its format as a choirbook (all parts appear on adjacent pages), and its vertical orientation. It includes fifty-four musical works, only one of which is explicitly attributed (it is piece no. 49, Dezilde al cavallero, whose composer is identified as the Flemish musician Nicolas Gombert). The authorship of other works has been later established or inferred by musicologists: a few songs included in this songbook were also found in other collections, where their composer was explicitly indicated, while other pieces have been attributed for stylistic reasons.

As proclaimed by the titlepage, the collection consists mostly of villancicos, a genre of madrigals typical for Spanish Renaissance music, and comprising both sacred and secular works, along with eight duets unprovided with sung lyrics. The songs are organized in the publication according to the number of parts; this, together with the indication that some songs are “suited for those who are beginners in singing” has suggested to musicologists that the songbook may have had an intended educational or pedagogic value. Moreover, the specification “newly corrected” leads to the inference that the Scotto edition might represent a later emendation of an earlier (printed or unprinted, but already circulating) version. Following the table of contents, the reader finds twelve two-part villancicos, twelve in three parts, twelve in four parts, as well as twelve Christmas villancicos and eight more five-part villancicos. Almost all lyrics are in Castilian, while four are in Catalan (one of which employs a Gascogne dialect); yet another includes a section sung in Latin and one is in the Galician language.

The specimen found by Mitjana currently remains the only known copy of the printing. In 1909, as previously mentioned, its discoverer published a famous article, discussing twenty-eight of the poems set to music in the songbook. His work was reprinted in Mexico in 1944, along with an essay by Isabel Pope, by Jesús Bal y Gay, who also published the music for the first time. Another influential study appeared in 1958, written by Josep Romeu Figueras, and focusing on the figure of Mateo Flecha the Elder; this article was the first to connect the songbook (which had been known as the Cancionero de Uppsala up to that moment) with the Duke of Calabria and its Court. This destination has recently been disputed by musicologist Emilio Ros-Fábregas, who points out that no reference to the Duke, no family crests, and no works by local composers are found in the book. He also interestingly suggests a narrative interpretation of the entire collection: different from other so-called cancioneros, which were compiled by copyists who might not follow an “editorial” plan, this printed collection presents, in his opinion, a “theological” structure focusing on the redemption of sins through the Incarnation of Christ. While Ros-Fábregas’ contentions are being discussed by the specialists in the field, the Cancionero is still commonly known and referred to as the Cancionero del Duque de Calabria, the Duke of Calabria’s Songbook.

According to Romeu Figueras, the Cancionero originated in Valencia, at the court of Fernando of Aragon (1488-1550) and of his wife, Germana de Foix. The connection with Fernando might therefore explain the high proportion of Christmas songs found in the collection; in fact, it was believed that Fernando’s ancestry dated back to Balthasar, one of the three Wise Men who, according to the Gospel of Luke, had worshipped the Child Jesus shortly after his birth.

Fernando’s youthful years had been rather eventful. The firstborn of Fredrick, the King of Naples, Fernando spent eleven years in captivity, before being released by Charles I in 1523, who also arranged his marriage with Germana; the couple married in Sevilla in 1526, but their life together lasted only ten years. Fernando’s title of Duke of Calabria was later complemented by that of Viceroy of Valencia. After Germana’s death, Fernando remarried: both of his wives, Germana and Mencía de Mendoza, were highly cultivated patronesses of the arts. His musical chapel was refined, and its masters were chosen among the leading musicians of the era; among them are Pedro de Pastrana (from 1529 to 1533) and Juan de Cepa (from 1544 to 1554), while the presence of Mateo Flecha the Elder at his court is still being disputed. Certainly, the Chapel’s quality was famous throughout Europe, and contributed to the Court’s fame crucially. It is therefore rather likely that, at Fernando’s death, this collection could have been intended as a posthumous homage to his culture and to the artistic level of his court. The fact that the only extant copy is found in Uppsala is still unexplained, though it is rather likely that this specimen found its way to Sweden during or after the Thirty Years War, possibly after having travelled as far East as to Vienna and Prague or Poland.

The composers who have been identified, along with Gombert, are Juan del Encina, Cristóbal de Morale, Bartomeu Càceres and Francisco de Peñalosa, although the Cancionero has still much to reveal. The instrumental pieces mirror the Spanish musical culture as it expressed itself not only within the borders of the Iberian Peninsula, but also in many other territories under Spanish rule, such as the Kingdom of Naples.

On the other hand, the vocal pieces seem to display a direct link with another collection of songs, the so-called Cancionero de Palacio, probably dating back to the last decades of the fifteenth century. These collections display a fascinating variety of styles and genres, among which villancicos, refined polyphony and folk tunes, both sacred and secular.

The performance recorded here is particularly interesting for several reasons. It generously employs the sweet tones of the vihuela and of the viols. These instruments sound differently from each other, but they are in fact closely related, also for historical reasons. The vihuela actually is a typically Spanish instrument, which arrived in the Italian Peninsula within the chapel of the Valencian Rodrigo Borja, who would later become Pope as Alexander VI. In Italy, the vihuela changed its shape and features, and gradually became the Italian viola da gamba.

Taking advantage from the warm and expressive timbral fabric provided by these instruments, the performance recorded here opted for a practice in line with contemporaneous habits. The lower parts are not sung, but played instrumentally, thus allowing for a greater timbral variety; moreover, the sung texts become more clearly intelligible, following a concern which was widely shared by humanist thinkers, poets and Churchmen alike. Practices such as these would ultimately create the space for the emergence of accompanied monody, and for the development of a harmonic and tonal concept, leading straightforwardly to Baroque aesthetics and to the birth of wholly new genres and styles.

Chiara Bertoglio

While the reception history of this songbook is well documented and fascinating, very little is known about its origins, opening the gates for speculations and musicological debate. The history of its reception officially begins in 1909, with an article published by Rafael Mitjana Gordon (1869-1921). Mitjana was the Secretary to the Spanish Embassy in Stockholm, Sweden. During his stay in the Scandinavian country, in 1907, Mitjana took the opportunity of studying the holdings of an august library, in one of the oldest Universities of Europe, the University of Uppsala. In the Library known as Carolina Rediviva, his interest was caught by a relatively small book. It was a printed copy of a Venetian publication of the sixteenth century, realized by one of the most important music publishers of the era, i.e. Girolamo Scotto. The book’s complete title is “Villancicos de diversos Autores, a dos, y a tres, y a quatro, y a cinco bozes, agora nuevamente corregidos. Hay mas ocho tonos de Canto llano, y ocho tonos de Canto de Organo para que puedan aprovechar los que a cantar començaren. Venetiis, Apud Hieronymum Scotum, MDLVI”, and it actually provides us with the most detailed and reliable information we have about it.

In fact, and in an entirely unusual fashion for its time, the songbook has no dedication or preface, thus making it difficult to reconstruct the occasion or destination for which it was conceived. It is unusual also for many other reasons: it small size (209 x 147 mm), its format as a choirbook (all parts appear on adjacent pages), and its vertical orientation. It includes fifty-four musical works, only one of which is explicitly attributed (it is piece no. 49, Dezilde al cavallero, whose composer is identified as the Flemish musician Nicolas Gombert). The authorship of other works has been later established or inferred by musicologists: a few songs included in this songbook were also found in other collections, where their composer was explicitly indicated, while other pieces have been attributed for stylistic reasons.

As proclaimed by the titlepage, the collection consists mostly of villancicos, a genre of madrigals typical for Spanish Renaissance music, and comprising both sacred and secular works, along with eight duets unprovided with sung lyrics. The songs are organized in the publication according to the number of parts; this, together with the indication that some songs are “suited for those who are beginners in singing” has suggested to musicologists that the songbook may have had an intended educational or pedagogic value. Moreover, the specification “newly corrected” leads to the inference that the Scotto edition might represent a later emendation of an earlier (printed or unprinted, but already circulating) version. Following the table of contents, the reader finds twelve two-part villancicos, twelve in three parts, twelve in four parts, as well as twelve Christmas villancicos and eight more five-part villancicos. Almost all lyrics are in Castilian, while four are in Catalan (one of which employs a Gascogne dialect); yet another includes a section sung in Latin and one is in the Galician language.

The specimen found by Mitjana currently remains the only known copy of the printing. In 1909, as previously mentioned, its discoverer published a famous article, discussing twenty-eight of the poems set to music in the songbook. His work was reprinted in Mexico in 1944, along with an essay by Isabel Pope, by Jesús Bal y Gay, who also published the music for the first time. Another influential study appeared in 1958, written by Josep Romeu Figueras, and focusing on the figure of Mateo Flecha the Elder; this article was the first to connect the songbook (which had been known as the Cancionero de Uppsala up to that moment) with the Duke of Calabria and its Court. This destination has recently been disputed by musicologist Emilio Ros-Fábregas, who points out that no reference to the Duke, no family crests, and no works by local composers are found in the book. He also interestingly suggests a narrative interpretation of the entire collection: different from other so-called cancioneros, which were compiled by copyists who might not follow an “editorial” plan, this printed collection presents, in his opinion, a “theological” structure focusing on the redemption of sins through the Incarnation of Christ. While Ros-Fábregas’ contentions are being discussed by the specialists in the field, the Cancionero is still commonly known and referred to as the Cancionero del Duque de Calabria, the Duke of Calabria’s Songbook.

According to Romeu Figueras, the Cancionero originated in Valencia, at the court of Fernando of Aragon (1488-1550) and of his wife, Germana de Foix. The connection with Fernando might therefore explain the high proportion of Christmas songs found in the collection; in fact, it was believed that Fernando’s ancestry dated back to Balthasar, one of the three Wise Men who, according to the Gospel of Luke, had worshipped the Child Jesus shortly after his birth.

Fernando’s youthful years had been rather eventful. The firstborn of Fredrick, the King of Naples, Fernando spent eleven years in captivity, before being released by Charles I in 1523, who also arranged his marriage with Germana; the couple married in Sevilla in 1526, but their life together lasted only ten years. Fernando’s title of Duke of Calabria was later complemented by that of Viceroy of Valencia. After Germana’s death, Fernando remarried: both of his wives, Germana and Mencía de Mendoza, were highly cultivated patronesses of the arts. His musical chapel was refined, and its masters were chosen among the leading musicians of the era; among them are Pedro de Pastrana (from 1529 to 1533) and Juan de Cepa (from 1544 to 1554), while the presence of Mateo Flecha the Elder at his court is still being disputed. Certainly, the Chapel’s quality was famous throughout Europe, and contributed to the Court’s fame crucially. It is therefore rather likely that, at Fernando’s death, this collection could have been intended as a posthumous homage to his culture and to the artistic level of his court. The fact that the only extant copy is found in Uppsala is still unexplained, though it is rather likely that this specimen found its way to Sweden during or after the Thirty Years War, possibly after having travelled as far East as to Vienna and Prague or Poland.

The composers who have been identified, along with Gombert, are Juan del Encina, Cristóbal de Morale, Bartomeu Càceres and Francisco de Peñalosa, although the Cancionero has still much to reveal. The instrumental pieces mirror the Spanish musical culture as it expressed itself not only within the borders of the Iberian Peninsula, but also in many other territories under Spanish rule, such as the Kingdom of Naples.

On the other hand, the vocal pieces seem to display a direct link with another collection of songs, the so-called Cancionero de Palacio, probably dating back to the last decades of the fifteenth century. These collections display a fascinating variety of styles and genres, among which villancicos, refined polyphony and folk tunes, both sacred and secular.

The performance recorded here is particularly interesting for several reasons. It generously employs the sweet tones of the vihuela and of the viols. These instruments sound differently from each other, but they are in fact closely related, also for historical reasons. The vihuela actually is a typically Spanish instrument, which arrived in the Italian Peninsula within the chapel of the Valencian Rodrigo Borja, who would later become Pope as Alexander VI. In Italy, the vihuela changed its shape and features, and gradually became the Italian viola da gamba.

Taking advantage from the warm and expressive timbral fabric provided by these instruments, the performance recorded here opted for a practice in line with contemporaneous habits. The lower parts are not sung, but played instrumentally, thus allowing for a greater timbral variety; moreover, the sung texts become more clearly intelligible, following a concern which was widely shared by humanist thinkers, poets and Churchmen alike. Practices such as these would ultimately create the space for the emergence of accompanied monody, and for the development of a harmonic and tonal concept, leading straightforwardly to Baroque aesthetics and to the birth of wholly new genres and styles.

Chiara Bertoglio

![Sachi Hayasaka & Stir Up - Free Fight (Remastered) (2026) [Hi-Res] Sachi Hayasaka & Stir Up - Free Fight (Remastered) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770839196_nctvwqu7dwhcc_600.jpg)