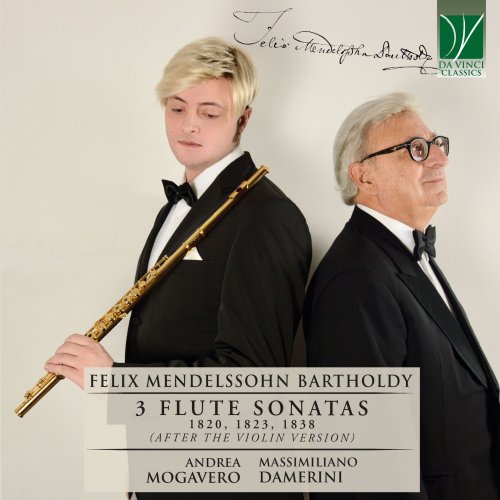

Andrea Mogavero, Massimiliano Damerini - Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: 3 Flute Sonatas 1820, 1823, 1838 (After the Violin Version) (2021)

Artist: Andrea Mogavero, Massimiliano Damerini

Title: Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: 3 Flute Sonatas 1820, 1823, 1838 (After the Violin Version)

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless

Total Time: 01:00:52

Total Size: 288 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy: 3 Flute Sonatas 1820, 1823, 1838 (After the Violin Version)

Year Of Release: 2021

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless

Total Time: 01:00:52

Total Size: 288 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

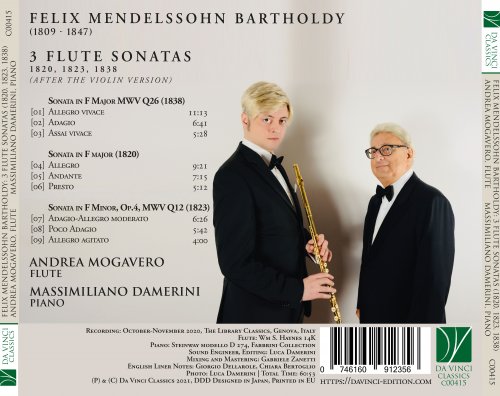

01. Violin Sonata in F Major, MWV Q 26: I. Allegro vivace

02. Violin Sonata in F Major, MWV Q 26: II. Adagio

03. Violin Sonata in F Major, MWV Q 26: III. Assai vivace

04. Violin Sonata in F Major, MWV Q 7: I. Allegro

05. Violin Sonata in F Major, MWV Q 7: II. Andante

06. Violin Sonata in F Major, MWV Q 7: III. Presto

07. Violin Sonata in F Minor, Op. 4: I. Adagio-Allegro moderato

08. Violin Sonata in F Minor, Op. 4: II. Poco Adagio

09. Violin Sonata in F Minor, Op. 4: III. Allegro agitato

The practice of transcribing a musical work originally conceived for an instrumental medium or ensemble, and to transform it into a piece for a different sound medium is an extremely ancient artistic form in its own right. Among the main qualities of sound, traditionally described as pitch, intensity and timbre, the last is frequently considered as the least important, or the most expendable. Thus, for some, transcription is simply the mechanical transposition of some “notes” from one timbre to another. On the other hand, others acquiesce too readily to the prescriptions of “authenticity” and “fidelity” (which seem occasionally to have displaced creativity as the highest criterion for judging a musical performance). For those listeners, only the sound originally conceived and heard by the composer is worth pursuing, and all other versions are more or less deplorable betrayals.

Both criticisms miss the point, of course. Firstly, in fact, even when two instruments play the same “notes”, a noteworthy degree of creativity is required of the “transcriber”. A number of interpretive choices must be taken, and they require a mature musical personality, one capable to engage with the composer’s style, musical imagination and writing when reproducing the piece on another musical medium. For instance, every instrument possesses peculiar sound qualities throughout the spectrum of its range; one instrument’s most brilliant or most powerful octave may be very different from those of an instrument with a similar range. Moreover, there are objective impossibilities, such as performing double stops or chords on a monodic instrument, or slight differences in range which force the performer to modify some notes. Choices regarding breathing, articulation, dynamics and tempo should also be made, and they may conflict with those established in the performing tradition of the original medium. This brief survey demonstrates the “artistry” of the transcription process, and that this process is worth of consideration as an intensely creative undertaking.

Moreover, a properly understood concept of “authenticity” is not bound to an antiquarian model of pure restoration of a lost sound. Though it is undoubtedly praiseworthy for some artists to engage, in cooperation with musicologists, in the reconstruction of period sonorities, instruments and performing practices (and these operations may be very creative in turn!), another kind of authenticity might rightfully claim that to be authentic is to be creative. If Baroque, Classical or Romantic composers did imagine that their works would be played after centuries (and it is likely that this idea never crossed the mind of many of them), they would have been probably surprised by our attempts to reconstruct “their” sound. Music used to be a living art, an art in process; an art in which adaptation was welcome, and the possibility of finding new ideas in older pieces was encouraged. Thus, one could say that fidelity to the spirit of the musicians whose works we play might imply a certain freedom as concerns the fidelity to the letter of their scores.

For this reason, a challenge such as that undertaken in this Da Vinci Classics album is a highly artistic, a perfectly legitimate and a thought-provoking one. At first sight, the violin (for which these Sonatas were originally written) and the flute may seem to share many qualities: both are high-pitched instruments (though the flute’s low notes are sensibly higher than the violin’s), both share a vocation as a solo instrument, and both are well suited to both expressivity and virtuosity. Yet, the differences are also numerous, and they are so important that the idea of playing Mendelssohn’s Violin Sonatas on the flute is daring and fascinating at the same time.

Among the many challenging aspects of this change of destination is undoubtedly the luxuriant and brilliant writing of these pieces. Mendelssohn was an exceptionally accomplished performer of both the piano and the violin, and therefore his writing is extremely idiomatic for both instruments. The piano part, in all of his chamber works with piano, is lavishly decorated and highly virtuosic; and while the overabundance of piano notes does never threaten to submerge the violin, when the partner is the flute the right sound balance is harder to find. The result, however, is revealing. The performance on the flute brings to light some hidden qualities of the original, and it further increases the enchanted and enchanting dimension of these pieces. The flute’s sound, which is more unearthly than that of the violin, contributes to an impression of pure magic and of supernatural beauty.

These features are even more striking when one considers the composition dates of these three pieces. The latest of them was written in 1838, when the composer was not yet thirty years old: by today’s standards, this would be a youthful work. Yet, in comparison with the other two pieces (and, sadly, considering its composer’s short life), this work belongs to Mendelssohn’s “late” period (he would die approximately ten years after its composition). The other two pieces were written when the composer was eleven and fourteen; still, they are not just the surprising affirmation of an immense musical talent, but rather they display a fully mature understanding of form, of scoring, and a lively musical creativity, blossoming with melodic, harmonic and rhythmical ideas.

It has been argued, rightly in my opinion, that Mendelssohn was the most precocious musical genius of all times. Indeed, some of his teenage works stand the test of time and have entered the Gotha of the absolute masterpieces of classical music. The Sonatas performed here are not among his most frequently played works, but doubtlessly belong among the works of a genius.

Certainly, his prodigious talent had found the right soil in his music-making and culture-loving family, where artistic stimuli abounded, and where some of the most important intellectuals of the era were usual guests (first and foremost Goethe). Moreover, Felix had the good fortune of being educated by an extremely sensible and clever musician, Carl Zelter (among whose many merits is also that of encouraging Felix’s study and appreciation of Bach, which would lead to the so called “Bach Renaissance”). The first to be composed, among the violin Sonatas performed here, dates from Mendelssohn’s years as Zelter’s pupil. Felix was eleven years old when he wrote it, but his mastery of counterpoint is convincing, skilled and fluent. An impressive feature of young Mendelssohn’s chamber music writing is the composer’s capability to realise a true dialogue between the instruments, as shown, for example, in their frequent taking turns in the presentation of the melodic material. The lyrical climax of this youthful piece is certainly represented by the splendid melodies of the second movement, in f minor, whose elegant and fresh variations represent yet another essay of the composer’s ability in treating the musical material. In the third movement, the listener is frequently surprised by the daring harmonic wanderings undertaken by the young musician, whose self-assuredness in the handling of the tonal relationships is such that he frequently abandons the calm waters of handbook harmony and ventures into distant tonal realms. Another remarkable feature of this movement is its reliance on a thematic structure based on flowing quadruplets: it is in fact an early demonstration of a constant stylistic trait of many Finale movements composed by Mendelssohn throughout his compositional career.

The second Sonata, op. 4, is the only one to which Mendelssohn gave an opus number. Although he was only fourteen at the time of its composition, it is a fully-fledged masterpiece in the somber key of f minor. Its memorable opening, with a solo recitative by the violin, sets the mood and opens the way for a thoroughly Romantic expressivity. This emerges both in the impassionate and powerful discourses of the outer movements, and in the more intimate and touching singing of the beautiful second movement. Here, Mendelssohn’s talent as a melodist is fully revealed, in the creation of unforgettable themes and in their skillful development. The Sonata also displays a cyclical concept, thanks to the presence of another violin recitative in the third movement, which closes the Sonata in an enchanted pianissimo.

The third Sonata was written fourteen years later, and had a curious doom: it was neglected at first by the composer himself, who later undertook a deep revision whose fulfilment was sadly interrupted by his untimely death. Then it lay abandoned for a century, until it was rediscovered, edited and published by Yehudi Menuhin in 1953. It is a magnificent piece, where almost all of the musical ideas and traits found in an already mature, but still youthful form in the earlier pieces find their accomplishment. Its dazzling Finale, a breathtaking whirlwind of notes, unites the child’s enthusiasm, the young man’s vitality, and the great artist’s skill, and is one of the remarkable moments of the entire chamber music repertoire.

Listening to the three Sonatas in a row is therefore a treat in itself, as it allows the audience to discover constant features and recurring elements within this series of masterpieces. Listening to them through the lens of the flute’s sound is still another bonus, as it highlights some unexpected traits which could go unnoticed even after repeated hearings. Needless to say, a composer with such a creative imagination as that displayed here would have thoroughly enjoyed the idea of discovering hidden qualities in his own works, thanks to the brilliant idea of performing them with the flute.

![Dino Siani - American Journey (2026) [Hi-Res] Dino Siani - American Journey (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770294888_ycfgnn93xzxpa_600.jpg)

![James Fernando - Philly 3 (2026) [Hi-Res] James Fernando - Philly 3 (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/06/x1z1d5tgfw7831grgh5do6jls.jpg)

![Oscar Peterson - The Sound Of The Trio (1961) [Vinyl 24-96] Oscar Peterson - The Sound Of The Trio (1961) [Vinyl 24-96]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2020-04/1587651652_613i2fde8wl__ss500_.jpg)