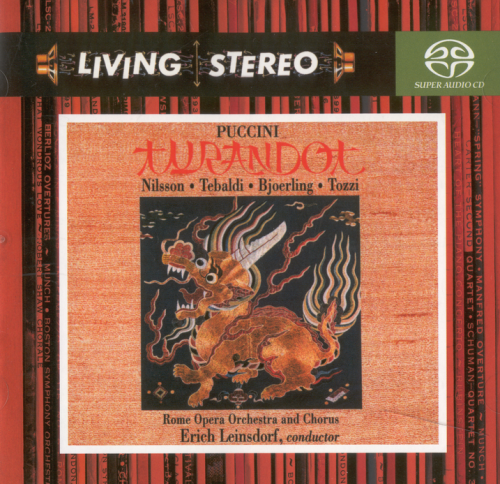

Erich Leinsdorf, Rome O.O. and Chorus - Puccini: Turandot (2006) [SACD]

Artist: Erich Leinsdorf, Rome O.O. and Chorus

Title: Puccini: Turandot

Year Of Release: 2006

Label: RCA / Living Stereo # 82876-82624-2

Genre: Opera, Orchestral

Quality: DSD64 image (*.iso) / 2.0, 5.0 (2,8 MHz/1 Bit)

Total Time: 1:55:01

Total Size: 5,08 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Puccini: Turandot

Year Of Release: 2006

Label: RCA / Living Stereo # 82876-82624-2

Genre: Opera, Orchestral

Quality: DSD64 image (*.iso) / 2.0, 5.0 (2,8 MHz/1 Bit)

Total Time: 1:55:01

Total Size: 5,08 GB

WebSite: Album Preview

Disc 1:

Act I:

01 - Popolo di Pekino! (5:31)

02 - Gira la cote, gira, gira! (2:29)

03 - Perchè tarda la luna? (4:01)

04 - O giovinotto (Funeral March) (3:06)

05 - O divina bellazza! (1:26)

06 - Figlio, che fai? T'arresta! (1:39)

07 - Fermo! Che fai? T'arresta! (3:56)

08 - Non indugiare! (2:06)

09 - Signore, ascolta! (2:34)

10 - Non piangere, Liù! (2:33)

11 - Ah! Per l'ultima volta! (2:43)

Act II:

Scene 1:

12 - Olà, Pang! Olà, Pong! (3:19)

13 - Ho una casa nell'Honan (3:01)

14 - O mondo ... O mondo ... (3:41)

15 - Non v'è in China per nostra fortuna (2:01)

Scene 2:

16 - Gravi, enormi ed imponenti (3:54)

17 - Un giuramento atroce mi costringe (4:16)

18 - Popolo di Pekino! (1:40)

Disc 2:

19 - In questa Reggia (6:10)

20 - Straniero, ascolta (2:17)

21 - ''Giuzza al pari di fiamma'' (2:11)

22 - ''Gelo che ti dà foco'' (3:14)

23 - Figlio del Cielo! (3:10)

24 - Tre enigmi m'hai proposto (1:47)

25 - Ai tuoi piedi ci postriam (2:12)

Act III:

Scene 1:

26 - Così comando Turandot (3:20)

27 - Nessun dorma! (3:20)

28 - Tu che guardi le stelle (2:25)

29 - Straniero, tu non sai (1:36)

30 - Principessa divina! (3:51)

31 - Chi pose tanta forza (3:24)

32 - Tu che di gel sei cinta (Death of Liù) (2:41)

33 - Ah! Tu sei morta (4:59)

34 - Principessa di morte! (3:33)

35 - Che è mai di me? (2:38)

36 - Del primo pianto (4:57)

Scene 2:

37 - Diecimila anni (3:03)

With the underrepresentation of opera in the SACD catalogue, the appearance of four classic sets in the RCA series is to be welcomed, even if none contain libretti. Moreover, the included synopses have no cue points to help direct the novice.

No matter. This particular recording has three of the great singers of the postwar era : Birgit Nilsson, Renata Tebaldi and Jussi Björling; respectively Turandot, Liu and Calaf. I have to confess that I am no great fan of this opera, having never even seen it in the opera house. Nevertheless, the opportunity of hearing these singers in the SACD format was irresistible. Of these three great musicians, only Nilsson to my knowledge has appeared on an SACD set, a Tannhäuser dating from about ten years later than this 1959 Puccini recording. Being too young to have heard Nilsson on stage, I was especially curious to hear how she sounded. On the CD medium, neither Callas nor Nilsson sound ideal, the former often a vinegary shriek, and Nilsson having a damascened edge as her voice rose triumphantly above the stave. I had suspected this was largely a recording artefact, and now there was an opportunity to find out.

In terms of the famous recordings of 'Turandot', this has generally been known as one of the three major sets, alongside the Decca productions of 1955 Borkh/ Tebaldi / Monaco, and the 1972 Sutherland / Caballé / Pavarotti conducted by Mehta. Hence, there is no need for me to specifically rate the artistic qualities of this classic 1959 production. Nilsson also completed a studio recording of Turandot in 1965 with Scotto and Corelli, and live versions of her exist from 1958, 1961 and 1964.

The four RCA releases were recorded in Rome, with the exception of 'Madama Butterfly', in the Rome Opera House. The sound which RCA gave these sets has the singers set quite forward, and the orchestra while sounding satisfyingly full on SACD, is much to the rear. The exaggerated stereo spread of the singers makes it seem that one is in the front row with respect to the voice. One way of assessing the balance between voice and orchestra in an opera recording is to assess the positioning of the chorus. Obviously in an opera hall, the orchestra is usually in a pit at the front of the stage, with the solo voices on stage in front of the chorus. In this performance, except for some sections where the chorus is off-stage, they sound forward with respect to the orchestra. Hence, this recording could never be called 'natural' [ the RCA set of Borkh singing Richard Strauss extracts in 1955 actually has a far better 'opera hall' ambience despite the dated recording ] in the live performance stakes.

The exaggerated stereo spread leads to 'Nessun Dorma' emanating solely from the left speaker when heard in stereo, a disconcerting experience. Comically, this is highlighted in the sections with the stupidly named characters of Ping, Pong and Pang. There is a production photo included of one of these sessions, where two of these singers are at the sides of the recording stage, and the third is in the middle. Leinsdorf can be seen in front of the middle singer, with his head turned back, presumably to look at the orchestra. Basically, Ping and Pong ping and pong between the left and right speakers. Doubtless if I utilised a centre channel, Pang would pang in the centre as much as Ping and Pong ping-pong on either side of Pang.

For me, Nilsson's singing steals the show. It is gloriously full throated and accurate. When she is recorded in the centre, her voice fills out in crescendos to completely cover the area between the speakers in a way which would never happen on stage, but this is an excess which only the pedantic will object to. The voices of the four main singers are never obscured by the orchestra, as can sometimes happen in the glorious Decca recording of 1972. Her performance of 'In questa Reggia' is stupendous in its command. Sure, I find Callas's classic 1954 studio performance of this aria under Serafin almost unique in its defiance and vulnerability, but the five years which separate these two recordings sound more like thirty years' difference in terms of recording quality. The Callas interpretations have a fiery [ and wobbly ] sense of Italianite line which eludes Nilsson, but this a difference in taste, rather than any true imbalance in artistic sensibility. However, Nilsson is partnered in this ethos by the conducting of Leinsdorf, which, fine though it is, also lacks that sense of fiery line characteristic of Mehta in 1972, and which Riccardo Muti generally flaunts in the operatic repertoire.

The 'steeliness' which others have remarked on as a characteristic of her timbre I cannot find in this recording. Intriguingly, the 24 bit/ 96kHz transfer of the Wagner from a decade later on SACD finds her voice with a slightly steely upper register, although it is much less marked than on CDs. I have no idea whether this was due to her voice being at its peak when the Puccini was made, or whether technology intruded. It must've been challenging for the microphones of the era to track her vocal amplitude. Presumably this 1959 recording employed valves, whereas the later Wagner recording may have employed solid state electronics which sullied the purity of the voice. Who knows.

Tebaldi has her usual creamy texture, and it is better captured here than in the CDs of the contemporaneous recording of 'Aida' that she made under Karajan for Decca. Björling's voice by this stage had started to lose its beautiful lustre, but it sounds well enough. He doesn't have the heroic ring of Pavarotti in 1972, but his performance has a cherishable lyrical and character-projecting quality which is quite touching. Nonetheless, in his duets with Nilsson, he would've been distinctly second best had the clarity of the RCA recording and its voice-friendly positioning not come to his rescue.

No matter. This particular recording has three of the great singers of the postwar era : Birgit Nilsson, Renata Tebaldi and Jussi Björling; respectively Turandot, Liu and Calaf. I have to confess that I am no great fan of this opera, having never even seen it in the opera house. Nevertheless, the opportunity of hearing these singers in the SACD format was irresistible. Of these three great musicians, only Nilsson to my knowledge has appeared on an SACD set, a Tannhäuser dating from about ten years later than this 1959 Puccini recording. Being too young to have heard Nilsson on stage, I was especially curious to hear how she sounded. On the CD medium, neither Callas nor Nilsson sound ideal, the former often a vinegary shriek, and Nilsson having a damascened edge as her voice rose triumphantly above the stave. I had suspected this was largely a recording artefact, and now there was an opportunity to find out.

In terms of the famous recordings of 'Turandot', this has generally been known as one of the three major sets, alongside the Decca productions of 1955 Borkh/ Tebaldi / Monaco, and the 1972 Sutherland / Caballé / Pavarotti conducted by Mehta. Hence, there is no need for me to specifically rate the artistic qualities of this classic 1959 production. Nilsson also completed a studio recording of Turandot in 1965 with Scotto and Corelli, and live versions of her exist from 1958, 1961 and 1964.

The four RCA releases were recorded in Rome, with the exception of 'Madama Butterfly', in the Rome Opera House. The sound which RCA gave these sets has the singers set quite forward, and the orchestra while sounding satisfyingly full on SACD, is much to the rear. The exaggerated stereo spread of the singers makes it seem that one is in the front row with respect to the voice. One way of assessing the balance between voice and orchestra in an opera recording is to assess the positioning of the chorus. Obviously in an opera hall, the orchestra is usually in a pit at the front of the stage, with the solo voices on stage in front of the chorus. In this performance, except for some sections where the chorus is off-stage, they sound forward with respect to the orchestra. Hence, this recording could never be called 'natural' [ the RCA set of Borkh singing Richard Strauss extracts in 1955 actually has a far better 'opera hall' ambience despite the dated recording ] in the live performance stakes.

The exaggerated stereo spread leads to 'Nessun Dorma' emanating solely from the left speaker when heard in stereo, a disconcerting experience. Comically, this is highlighted in the sections with the stupidly named characters of Ping, Pong and Pang. There is a production photo included of one of these sessions, where two of these singers are at the sides of the recording stage, and the third is in the middle. Leinsdorf can be seen in front of the middle singer, with his head turned back, presumably to look at the orchestra. Basically, Ping and Pong ping and pong between the left and right speakers. Doubtless if I utilised a centre channel, Pang would pang in the centre as much as Ping and Pong ping-pong on either side of Pang.

For me, Nilsson's singing steals the show. It is gloriously full throated and accurate. When she is recorded in the centre, her voice fills out in crescendos to completely cover the area between the speakers in a way which would never happen on stage, but this is an excess which only the pedantic will object to. The voices of the four main singers are never obscured by the orchestra, as can sometimes happen in the glorious Decca recording of 1972. Her performance of 'In questa Reggia' is stupendous in its command. Sure, I find Callas's classic 1954 studio performance of this aria under Serafin almost unique in its defiance and vulnerability, but the five years which separate these two recordings sound more like thirty years' difference in terms of recording quality. The Callas interpretations have a fiery [ and wobbly ] sense of Italianite line which eludes Nilsson, but this a difference in taste, rather than any true imbalance in artistic sensibility. However, Nilsson is partnered in this ethos by the conducting of Leinsdorf, which, fine though it is, also lacks that sense of fiery line characteristic of Mehta in 1972, and which Riccardo Muti generally flaunts in the operatic repertoire.

The 'steeliness' which others have remarked on as a characteristic of her timbre I cannot find in this recording. Intriguingly, the 24 bit/ 96kHz transfer of the Wagner from a decade later on SACD finds her voice with a slightly steely upper register, although it is much less marked than on CDs. I have no idea whether this was due to her voice being at its peak when the Puccini was made, or whether technology intruded. It must've been challenging for the microphones of the era to track her vocal amplitude. Presumably this 1959 recording employed valves, whereas the later Wagner recording may have employed solid state electronics which sullied the purity of the voice. Who knows.

Tebaldi has her usual creamy texture, and it is better captured here than in the CDs of the contemporaneous recording of 'Aida' that she made under Karajan for Decca. Björling's voice by this stage had started to lose its beautiful lustre, but it sounds well enough. He doesn't have the heroic ring of Pavarotti in 1972, but his performance has a cherishable lyrical and character-projecting quality which is quite touching. Nonetheless, in his duets with Nilsson, he would've been distinctly second best had the clarity of the RCA recording and its voice-friendly positioning not come to his rescue.

![Erich Leinsdorf, Rome O.O. and Chorus - Puccini: Turandot (2006) [SACD]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2021-07/1627286161_outside.png)

![Larry Coryell - Major Jazz Minor Blues (1998) [CDRip] Larry Coryell - Major Jazz Minor Blues (1998) [CDRip]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771860317_5.jpg)

![Matt Monro - Matt Sings Monro (Live at the BBC, Remastered 2023) [Hi-Res] Matt Monro - Matt Sings Monro (Live at the BBC, Remastered 2023) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771586614_k3yj19donljhc_600.jpg)