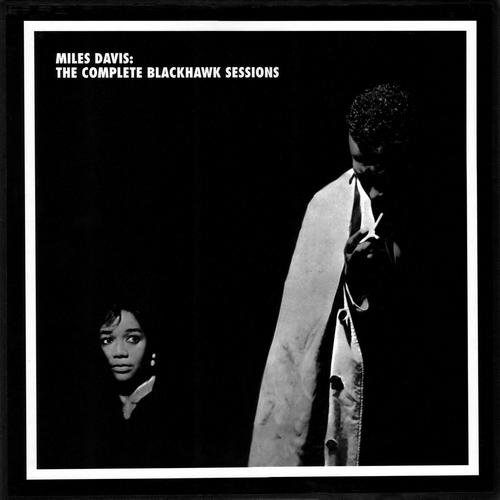

Miles Davis - The Complete Blackhawk Sessions [6LP Limited Edition Box Set] (2003)

Artist: Miles Davis

Title: The Complete Blackhawk Sessions

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: Mosaic Records [MQ6-220]

Genre: Jazz, Hard Bop, Modal Jazz

Quality: 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks, scans) / [96kHz/24bit]

Total Time: 3:59:39

Total Size: 577 mb / 1.46 gb / 4.75 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

Title: The Complete Blackhawk Sessions

Year Of Release: 2003

Label: Mosaic Records [MQ6-220]

Genre: Jazz, Hard Bop, Modal Jazz

Quality: 320 kbps / FLAC (tracks, scans) / [96kHz/24bit]

Total Time: 3:59:39

Total Size: 577 mb / 1.46 gb / 4.75 gb

WebSite: Album Preview

The 1961 Miles Davis Quintet has been relegated to footnote status in the trumpeter’s long and varied career. It has been said that this was one of Miles’ most popular groups on the club circuit. When you consider the degree of swing and compatibility that this group achieved, it is easy to see why.

This unit evolved over considerable time. Paul Chambers had been Miles Davis’ bassist of choice since the trumpeter first put together a quintet in 1955. Jimmy Cobb came in May 1958, shortly after his former boss Cannonball Adderley made the group a sextet. In early 1959, Wynton Kelly took over the chair that had been occupied by two very contrasting pianists Red Garland and Bill Evans, and he seemed to encompass Red’s swing and Bill’s intellect. This rhythm section clicked to such a degree that they remained musically and professionally inseparable until Chambers died in 1969.

Miles’ choices for tenor saxophonist leaned toward the more exploratory breed – Sonny Rollins, briefly, and then John Coltrane. When he added alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley to make the group a sextet, he couldn’t have squeezed two more contrasting saxophonists into his music. Adderley favored blues-based be-bop while Coltrane was focusing on mastering and expanding harmonic language. One can imagine a divided club audience – half routing for one saxophonist and the rest for the other. This made for exciting and unpredictable music and generated great ink in the jazz press.

When Coltrane left the band for the last time after a March-April 1960 European tour, Miles hired Jimmy Heath, who had travel restrictions and then the inveterate bebop master Sonny Stitt who stayed with the group to the end of the year. On December 26, Hank Mobley joined the group in Chicago.

With this line-up, Miles’ band reached a new level of simpatico. Coltrane, Adderley and Garland or Evans had wildly different styles. But as soloists, Miles, Mobley and Kelly spoke in melodic declarative sentences; they shared a sensibility and an aesthetic. Powered by Chambers and Cobb, they swung effortlessly, one solo seamlessly blending into the next.

They were a master class in the state of modern jazz in 1961.

Most likely the absence of tension or new ground or explosive unpredictability in their music caused them to be written off in the critical community. Mobley, particularly, got a bad rap as the weak link in the group. But he was always punished for a lack of flamboyance and never rewarded for being a singular, masterful artist. Even Miles would later say that Hank didn’t inspire him the way Coltrane did.

When the two resulting albums from the live appearances at the Blackhawk were issued, they were Miles Davis’ first live recordings. (His Newport and Plaza tapes had not yet been issued and the flurry of live radio broadcasts and bootlegs that flood the shelves today did not exist.) The absence of new material and controversial soloists probably made these recordings a failure in the ears of some. But now, we have almost every note this band played that weekend and none of it is less than sublime. We hear what they achieved on a nightly basis.

This unit evolved over considerable time. Paul Chambers had been Miles Davis’ bassist of choice since the trumpeter first put together a quintet in 1955. Jimmy Cobb came in May 1958, shortly after his former boss Cannonball Adderley made the group a sextet. In early 1959, Wynton Kelly took over the chair that had been occupied by two very contrasting pianists Red Garland and Bill Evans, and he seemed to encompass Red’s swing and Bill’s intellect. This rhythm section clicked to such a degree that they remained musically and professionally inseparable until Chambers died in 1969.

Miles’ choices for tenor saxophonist leaned toward the more exploratory breed – Sonny Rollins, briefly, and then John Coltrane. When he added alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley to make the group a sextet, he couldn’t have squeezed two more contrasting saxophonists into his music. Adderley favored blues-based be-bop while Coltrane was focusing on mastering and expanding harmonic language. One can imagine a divided club audience – half routing for one saxophonist and the rest for the other. This made for exciting and unpredictable music and generated great ink in the jazz press.

When Coltrane left the band for the last time after a March-April 1960 European tour, Miles hired Jimmy Heath, who had travel restrictions and then the inveterate bebop master Sonny Stitt who stayed with the group to the end of the year. On December 26, Hank Mobley joined the group in Chicago.

With this line-up, Miles’ band reached a new level of simpatico. Coltrane, Adderley and Garland or Evans had wildly different styles. But as soloists, Miles, Mobley and Kelly spoke in melodic declarative sentences; they shared a sensibility and an aesthetic. Powered by Chambers and Cobb, they swung effortlessly, one solo seamlessly blending into the next.

They were a master class in the state of modern jazz in 1961.

Most likely the absence of tension or new ground or explosive unpredictability in their music caused them to be written off in the critical community. Mobley, particularly, got a bad rap as the weak link in the group. But he was always punished for a lack of flamboyance and never rewarded for being a singular, masterful artist. Even Miles would later say that Hank didn’t inspire him the way Coltrane did.

When the two resulting albums from the live appearances at the Blackhawk were issued, they were Miles Davis’ first live recordings. (His Newport and Plaza tapes had not yet been issued and the flurry of live radio broadcasts and bootlegs that flood the shelves today did not exist.) The absence of new material and controversial soloists probably made these recordings a failure in the ears of some. But now, we have almost every note this band played that weekend and none of it is less than sublime. We hear what they achieved on a nightly basis.

TRACKLIST:

A1 Oleo 6:55

A2 No Blues 17:13

A3 Bye Bye (Theme) 2:54

B1 All Of You 15:28

B2 Neo 10:09

C1 I Thought About You 4:52

C2 Bye Bye Blackbird 9:44

D1 Walkin' 14:14

D2 Love, I've Found You 1:48

E1 If I Were A Bell 12:43

E2 Fran Dance 7:31

F1 On Green Dolphin Street 12:10

F2 The Theme 0:37

G1 If I Were A Bell 12:43

G2 So What 12:14

G3 No Blues 0:18

H1 On Green Dolphin Street 11:54

H2 Walkin' 12:13

I1 'Round Midnight 7:28

I2 Well You Needn't 8:02

I3 The Theme 0:09

J1 Autumn Leaves 11:30

J2 Neo 12:26

K1 Two Bass Hit 4:35

K2 Bye Bye (Theme) 3:19

K3 Love, I've Found You 1:45

K4 I Thought About You 5:31

L1 Someday My Prince Will Come 9:30

L2 Softly As In A Morning Sunrise 8:37

Bass – Paul Chambers

Drums – Jimmy Cobb

Ensemble – The Miles Davis Quintet

Piano – Wynton Kelly

Producer – Irving Townsend

Reissue Producer – Bob Belden, Michael Cuscuna

Tenor Saxophone – Hank Mobley

Trumpet – Miles Davis

Recorded live at Blackhawk, San Francisco, on Friday, April 21 and Saturday, April 22, 1961

Limited to 3,000 Copies