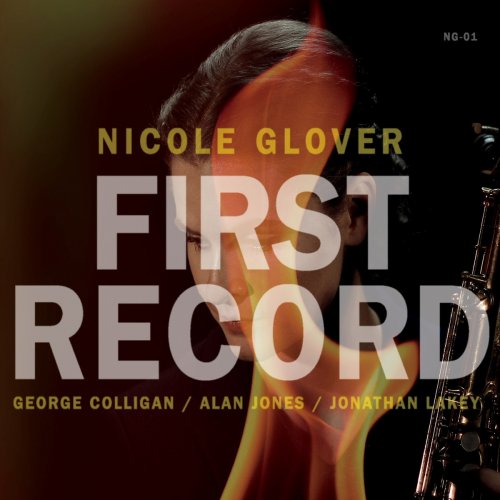

Nicole Glover - First Record (2015)

Artist: Nicole Glover

Title: First Record

Year Of Release: 2015

Label: Nicole Glover

Genre: Contemporary Jazz, Post-Bop

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, log, Artwork)

Total Time: 46:41

Total Size: 318 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: First Record

Year Of Release: 2015

Label: Nicole Glover

Genre: Contemporary Jazz, Post-Bop

Quality: FLAC (tracks+.cue, log, Artwork)

Total Time: 46:41

Total Size: 318 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Water Ritual (6:59)

02. Waning and Waxing (7:13)

03. Marshmallow (6:09)

04. Snow Dance (4:09)

05. String Quartet in F (7:23)

06. Blood Moon (4:54)

07. Conscience of the King (6:38)

08. Tennessee Waltz (3:16)

If for some reason Portland-native Nicole Glover's First Record ended up being her only one, she would still have made a lasting impact on the jazz world. The 24-year-old saxophonist's debut is an ambitious one that lays a lot on the table and seeks not only to establish her as a capable player, but a voice in the crowded world of jazz tenor. Aided by fellow Portlanders, both in her peer group (Jonathan Lakey on bass) and a few generations above her (George Colligan on piano and Alan Jones on drums), Glover's quartet record is a sonically and emotionally powerful one. It leaves aside niceties and dues- paying formalities and comes out swinging, shouting and dancing.

A significant aspect of First Record is a sense of contrast. Glover's originals seize on dichotomies and ranges of ideas in both intensity and function, sometimes over long periods of time and sometimes almost instantly. The first track, "Water Ritual," lilts out a pretty melody in 5/4 that gradually becomes edgier as Colligan's harmony becomes denser and more dissonant, almost as if the optimism of the melody is being called into question. Glover's solo takes a similar arc, shoving its way out of the groove and into an intense stratosphere of searing high notes and full-range atonality. She improvises as such on "Conscience of the King," arcing her solo up from the low, rhythmic vibe of the post-bop head into twisty combinations of runs, tremolos and single-note stabs. Glover's ideas, while organized and rhythmically pocketed, don't often follow the usual path of linear, swung, tension-to-resolution bop soloing. They sort of creep in unexpectedly, dart in unusual ways and explode by the time they're done. It's a textural approach, not just in terms of sound, but also the impression that it leaves after its finished.

The record's diverse trio of covers also celebrates contrast. Glover and Colligan rip their way through "Marshmallow" (an enormously complex Warne Marsh contrafact on "Cherokee" that pushes the limits of harmony and rhythm over familiar changes), wherein Glover wisely doesn't try to outdo the head and just deftly and learnedly plays the Cherokee harmony. She transforms a section of Maurice Ravel's "String Quartet in F" into a sprawling, bombastic jammer, taking on the decades old jazz tradition of taking the powerful melodies and impressionistic harmonies of Western classical music and turning the intensity up. Not all of the covers are war horses, though; her gentle take on Stewart and King's "Tennessee Waltz" is just as poignant and palatable as Patti Paige's version, lingering on gospel roots of the melody and letting Colligan expand into a loose-time expansion that sounds straight out of a church service.

As Glover's teacher and mentor in real life, Colligan's role on the record is no different. He lends his incredible and deft talent at the keys, but doesn't overshadow her. His solo on "Waning and Waxing" fits neatly into record's theme of neatness and beauty meeting unrestrained adventure, slowly evolving into wild, flowing runs with his right hand while the left hammers out polyrhythmic quarter notes. He's fully capable of allowing Glover to keep the spotlight on tunes like "Blood Moon," where he follows Glover's sinewy solo with one composed mostly of chords. Colligan even puts aside his keyboard chops for a pocket trumpet on "Snow Dance," which recalls the jolly melodies and abstract soundscapes of "New York is Now!"/"At Golden Circle"-era Ornette Coleman.

The quality that excites and promises the most from Glover is her simultaneous rejection of tenor saxophone clichés while still celebrating the instrument in its fullest. She mostly avoids the linear and harmonic pitfalls of obviousness that many young tenors mire in, and yet, nothing she plays would make sense on any other instrument. It does, of course, draw crucial bits and pieces from recognizable sources, from Wayne Shorter's mystery to John Coltrane's prayer-like intensity, reaching out to the reedy, understated rhythms of Marsh and Lee Konitz to the elusive and flammable zig-zags of players like Joe Henderson and Tony Malaby. Largely, though, Glover is making quick approaches to sole propriety of her own sound, which, especially for her age, is as important as it is rare.

A significant aspect of First Record is a sense of contrast. Glover's originals seize on dichotomies and ranges of ideas in both intensity and function, sometimes over long periods of time and sometimes almost instantly. The first track, "Water Ritual," lilts out a pretty melody in 5/4 that gradually becomes edgier as Colligan's harmony becomes denser and more dissonant, almost as if the optimism of the melody is being called into question. Glover's solo takes a similar arc, shoving its way out of the groove and into an intense stratosphere of searing high notes and full-range atonality. She improvises as such on "Conscience of the King," arcing her solo up from the low, rhythmic vibe of the post-bop head into twisty combinations of runs, tremolos and single-note stabs. Glover's ideas, while organized and rhythmically pocketed, don't often follow the usual path of linear, swung, tension-to-resolution bop soloing. They sort of creep in unexpectedly, dart in unusual ways and explode by the time they're done. It's a textural approach, not just in terms of sound, but also the impression that it leaves after its finished.

The record's diverse trio of covers also celebrates contrast. Glover and Colligan rip their way through "Marshmallow" (an enormously complex Warne Marsh contrafact on "Cherokee" that pushes the limits of harmony and rhythm over familiar changes), wherein Glover wisely doesn't try to outdo the head and just deftly and learnedly plays the Cherokee harmony. She transforms a section of Maurice Ravel's "String Quartet in F" into a sprawling, bombastic jammer, taking on the decades old jazz tradition of taking the powerful melodies and impressionistic harmonies of Western classical music and turning the intensity up. Not all of the covers are war horses, though; her gentle take on Stewart and King's "Tennessee Waltz" is just as poignant and palatable as Patti Paige's version, lingering on gospel roots of the melody and letting Colligan expand into a loose-time expansion that sounds straight out of a church service.

As Glover's teacher and mentor in real life, Colligan's role on the record is no different. He lends his incredible and deft talent at the keys, but doesn't overshadow her. His solo on "Waning and Waxing" fits neatly into record's theme of neatness and beauty meeting unrestrained adventure, slowly evolving into wild, flowing runs with his right hand while the left hammers out polyrhythmic quarter notes. He's fully capable of allowing Glover to keep the spotlight on tunes like "Blood Moon," where he follows Glover's sinewy solo with one composed mostly of chords. Colligan even puts aside his keyboard chops for a pocket trumpet on "Snow Dance," which recalls the jolly melodies and abstract soundscapes of "New York is Now!"/"At Golden Circle"-era Ornette Coleman.

The quality that excites and promises the most from Glover is her simultaneous rejection of tenor saxophone clichés while still celebrating the instrument in its fullest. She mostly avoids the linear and harmonic pitfalls of obviousness that many young tenors mire in, and yet, nothing she plays would make sense on any other instrument. It does, of course, draw crucial bits and pieces from recognizable sources, from Wayne Shorter's mystery to John Coltrane's prayer-like intensity, reaching out to the reedy, understated rhythms of Marsh and Lee Konitz to the elusive and flammable zig-zags of players like Joe Henderson and Tony Malaby. Largely, though, Glover is making quick approaches to sole propriety of her own sound, which, especially for her age, is as important as it is rare.