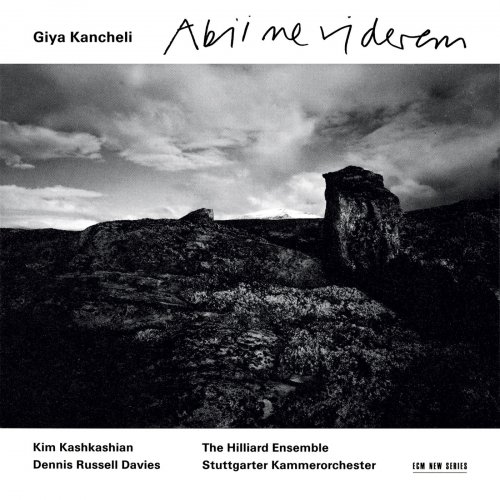

Kim Kashkashian, The Hilliard Ensemble, Dennis Russell Davies - Giya Kancheli: Abii ne viderem (1995)

Artist: Kim Kashkashian, The Hilliard Ensemble, Dennis Russell Davies

Title: Giya Kancheli: Abii ne viderem

Year Of Release: 1995

Label: ECM New Series

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:08:04

Total Size: 199 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist: Title: Giya Kancheli: Abii ne viderem

Year Of Release: 1995

Label: ECM New Series

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 01:08:04

Total Size: 199 Mb

WebSite: Album Preview

1. Morning Prayers (For Chamber Orchestra, Voice And Alto Flute) 22:52

2. Abii Ne Viderem (For String Orchestra And Viola) 25:25

3. Evening Prayers (For Chamber Orchestra And Voices) 19:53

Performers:

The Hilliard Ensemble

Kim Kashkashian Viola

David James Countertenor

David Gould Countertenor

Rogers Covey-Crump Tenor

John Potter Tenor

Vasiko Tevdorashvili Voice

Natalia Pschenitschnikova Alto Flute

Stuttgarter Kammerorchester

Dennis Russell Davies Conductor

My first exposure to the music of Giya Kancheli, with which the composer once said, “I feel more as if I were filling a space that has been deserted,” was through Exil, which remains in my opinion the finest ECM New Series release to date. Much in contrast to the tearful beauty of that most significant chamber album, the orchestral arrangements on Abii ne viderem—drawn as they are from the same thematic sources—lend extroverted articulation to essentially “monastic” material. This music may speak the same language, but in a far more distant dialect. The Life without Christmas cycle, from which two pieces bookend the present recording, is central to the Kancheli oeuvre. Not only is it his wellspring, but it also comprises, it would seem, the overarching worldview under which he musically operates. It is the gloom of a life of displacement, the full embodiment of what Hans-Klaus Jungheinrich calls “measured gravity,” which may perhaps be likened to the heavy emptiness of Tarkovsky’s Stalker. As in said film, every gesture makes a footprint, a remnant of human presence left to sink into the submerged wasteland of a silent future.

Morning Prayers (1990) is immediately distinguished by an angelic boy soprano, whose taped voice is never fully grounded but which hovers throughout. The piano adds another haunting element, seeming to pull at the barbed ends of nostalgia even as it pushes the orchestra down a flight of descendent chords. Occasional violent moments startle us into self-awareness and only serve to underscore the power of the prayers that surround them. The most profoundly effective moment occurs when the piano echoes in a dance-like theme, the orchestral accompaniment slightly off center—a distant memory ravaged by time and circumstance.

The title of the album’s central piece, Abii ne viderem (1992/94), translates to “I turned away so as not to see.” The more one listens to it, the question becomes not what is being turned away from but what is being observed upon turning. Its paced staccato bursts are linked by a profound silence, escalating with every reiteration. This silence eventually opens into a full orchestral statement, italicized again by the piano’s audible pulse. We find ourselves caught in the middle of a larger web of sentiments, until we can no longer see ourselves for who we are but only for who we have been. Personally, I find this piece to be a touch overbearing, if only because the import of its ideas is easily crushed by the heft of its dynamic spread.

The presence of the Hilliard Ensemble rescues Evening Prayers (1991) from the didacticism of its predecessor. It is a more fully unified narrative, linked by a lingering alto flute. A gorgeous “ascension” passage marks a rare contrapuntal moment for Kancheli, while David James’s voice creates magic, ever so subtly offset by a skittering violin. Occasional bursts, some punctuated by snare drum, break the mood and ensure that our attention is held. Inevitably, the piece ends like a ship sailing into a foggy ocean, leaving behind only a blank map to show for our travels.

Don’t let any comparisons to Arvo Pärt lure you astray. Kancheli’s music, while transcendent, cannot be divorced from its rootedness in upheaval. And while this album may be filled with beautiful moments, I cannot help but feel that something gets elided in these grander arrangements. I say this with the gentlest of criticisms, and perhaps only because my first foray into this world was on such a small scale. The sound of Exil stays with me, and sometimes I just cannot hear it in any other context, and for those wishing to hear this composer for the first time I would recommend starting there. That being said, the scale of these pieces makes them no less evocative for all their historical understatements and sensitivity. And perhaps that is Kancheli’s underlying observation: that, in our current climate of convalescent ideologies, all we have to hold on to are those rare flashes of fire in which our communion with something greater has transcended the rising waters of sociopolitical corruption.

Morning Prayers (1990) is immediately distinguished by an angelic boy soprano, whose taped voice is never fully grounded but which hovers throughout. The piano adds another haunting element, seeming to pull at the barbed ends of nostalgia even as it pushes the orchestra down a flight of descendent chords. Occasional violent moments startle us into self-awareness and only serve to underscore the power of the prayers that surround them. The most profoundly effective moment occurs when the piano echoes in a dance-like theme, the orchestral accompaniment slightly off center—a distant memory ravaged by time and circumstance.

The title of the album’s central piece, Abii ne viderem (1992/94), translates to “I turned away so as not to see.” The more one listens to it, the question becomes not what is being turned away from but what is being observed upon turning. Its paced staccato bursts are linked by a profound silence, escalating with every reiteration. This silence eventually opens into a full orchestral statement, italicized again by the piano’s audible pulse. We find ourselves caught in the middle of a larger web of sentiments, until we can no longer see ourselves for who we are but only for who we have been. Personally, I find this piece to be a touch overbearing, if only because the import of its ideas is easily crushed by the heft of its dynamic spread.

The presence of the Hilliard Ensemble rescues Evening Prayers (1991) from the didacticism of its predecessor. It is a more fully unified narrative, linked by a lingering alto flute. A gorgeous “ascension” passage marks a rare contrapuntal moment for Kancheli, while David James’s voice creates magic, ever so subtly offset by a skittering violin. Occasional bursts, some punctuated by snare drum, break the mood and ensure that our attention is held. Inevitably, the piece ends like a ship sailing into a foggy ocean, leaving behind only a blank map to show for our travels.

Don’t let any comparisons to Arvo Pärt lure you astray. Kancheli’s music, while transcendent, cannot be divorced from its rootedness in upheaval. And while this album may be filled with beautiful moments, I cannot help but feel that something gets elided in these grander arrangements. I say this with the gentlest of criticisms, and perhaps only because my first foray into this world was on such a small scale. The sound of Exil stays with me, and sometimes I just cannot hear it in any other context, and for those wishing to hear this composer for the first time I would recommend starting there. That being said, the scale of these pieces makes them no less evocative for all their historical understatements and sensitivity. And perhaps that is Kancheli’s underlying observation: that, in our current climate of convalescent ideologies, all we have to hold on to are those rare flashes of fire in which our communion with something greater has transcended the rising waters of sociopolitical corruption.

![Piero Piccioni - La Spiaggia - The Beach (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) (2026) [Hi-Res] Piero Piccioni - La Spiaggia - The Beach (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack) (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/03/uasuoa9tpx4fgqf2agcpx1qg3.jpg)

![Vesna Pisarovic - Poravna (2025) [Hi-Res] Vesna Pisarovic - Poravna (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770024886_xcr9mudmw50b1it2dr9qpqkv0.jpg)

![Donna Privana - The Inverted Third (2026) [Hi-Res] Donna Privana - The Inverted Third (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1770018326_cover.jpg)