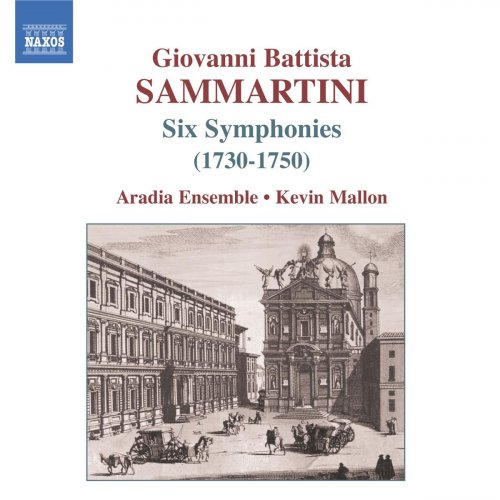

Aradia Ensemble, Kevin Mallon - Sammartini, G.B.: Symphonies J-C 4, 9, 16, 23, 36, 62 (2005)

Artist: Aradia Ensemble, Kevin Mallon

Title: Sammartini, G.B.: Symphonies J-C 4, 9, 16, 23, 36, 62

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless +Booklet

Total Time: 01:00:23

Total Size: 308 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Sammartini, G.B.: Symphonies J-C 4, 9, 16, 23, 36, 62

Year Of Release: 2005

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless +Booklet

Total Time: 01:00:23

Total Size: 308 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Symphony in A Major, J-C 62: I. Presto

02. Symphony in A Major, J-C 62: II. Andante e pianissimo

03. Symphony in A Major, J-C 62: IIIa. Presto assai

04. Symphony in A Major, J-C 62: IIIb. Allegro (alternative finale)

05. Symphony in C Minor, J-C 9: I. Allegro

06. Symphony in C Minor, J-C 9: II. Affettuoso

07. Symphony in C Minor, J-C 9: III. Allegro

08. Symphony in D Major, J-C 16: I. Alla breve

09. Symphony in D Major, J-C 16: II. Andante sempre piano

10. Symphony in D Major, J-C 16: III. Presto

11. Symphony in F Major, J-C 36: I. Presto

12. Symphony in F Major, J-C 36: II. Andante

13. Symphony in F Major, J-C 36: III. Allegro assai

14. Symphony in D Minor, J-C 23: I. Allegro

15. Symphony in D Minor, J-C 23: II. Grave

16. Symphony in D Minor, J-C 23: III. Presto

17. Symphony in C Major, J-C 4: I. Allegrissimo

18. Symphony in C Major, J-C 4: II. Andante e affettuoso

19. Symphony in C Major, J-C 4: III. Allegrissimo

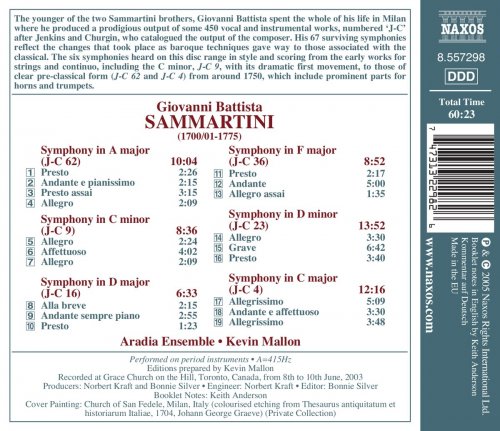

The precise date of Sammartini’s birth can only be inferred from the fact that he died in 1775, when his age was given as 74. It may be supposed that he was born in Milan, where his father Alexis Saint-Martin, to be known in Italy as Alessio Sammartini, a French oboist, had settled, and it has been suggested that his mother, Gerolama de Federici, came from the Milan family of oboists of that name. The seventh of eight children, Sammartini presumably studied with his father. His older brother Giuseppe, who seems to have served as an oboist for a time in the orchestra of the Teatro Regio Ducal in Milan, from the late 1720s won a reputation for himself in London, where he played in Handel’s opera orchestras and added significantly to the repertoire of sonatas and concertos, his playing an inspiration, it seems, to Handel, whose favourite instrument in his earlier years had been the hautbois. It is not known whether Giovanni Battista played the oboe or, indeed, the violin, but by the 1720s he was already active as a composer, becoming maestro di cappella of the Congregation of the Most Holy Sepulchre at the Jesuit church of San Fedele in 1728, a connection he maintained for the rest of his life. He later assumed similar positions with confraternities in a number of Milan churches, well known as a church musician, organist and composer, and, from 1768, maestro di cappella of the ducal court in Milan.

Although Sammartini seems to have spent his entire life in Milan or its environs, as the most distinguished composer there, he associated with many leading musicians who visited the city or worked there. While he may not have taught Gluck, who spent eleven years in Milan, from 1734, Sammartini certainly encouraged and influenced him, and in the following years exercised similar influence over the music of Johann Christian Bach, who became organist at Milan cathedral in 1760, while the cellist Boccherini played under his direction. Charles Burney, who visited Milan in 1770, described Sammartini’s music as ‘very ingenious, and full of the spirit and fire peculiar to that author’. Leopold Mozart, in Milan in the same year, wrote home to his wife describing how his son Wolfgang performed in the presence of Maestro Sammartini and of a number of the most distinguished people, and how he amazed them. Later in the year he was able to report the support of Sammartini, described as a true friend, after the local intrigues he suspected over the performance of his son’s first Milan opera, Mitridate, ré di Ponto. It was natural that Sammartini’s compositions should be heard in Vienna, and there is ample evidence of his contemporary fame elsewhere. Haydn, who would surely have heard works by Sammartini in Vienna, curtly rejected the suggestion of any such influence, yet it is clear that Sammartini had an important part to play in the development of instrumental music from the 1720s until his death.

An amazingly prolific composer, Sammartini wrote some 450 vocal and instrumental works. These include 67 surviving symphonies. The fact that a further 75 such works were ascribed to him is an indication of his reputation. The Sammartini scholar Bathia Churgin has suggested three stylistic periods for the composer’s symphonies, the first from the later 1720s to about 1739, the second to 1758 and the final period from then until 1774, based on other dated works, collections and references, and on stylistic characteristics. The system of numbering, J-C, is taken from the names of Newell Jenkins and Bathia Churgin, scholars particularly associated with research into and revival of Sammartini’s work. His activity as a composer over a period of some forty years reflects a number of the changes taking place, as baroque techniques gave way to those associated with the classical. Whatever Sammartini’s contemporary influence on this process, he may be seen as a pioneer in instrumental music, a precursor of the Mannheim school, and, indeed, of Haydn.

The symphonies included in the present recording are framed by two works dated to about 1750. The others belong to the earlier period of Sammartini’s career. The Symphony in A major, J-C 62, is scored for two trumpets and strings and survives in seven eighteenth-century copies, suggesting its contemporary diffusion. Six of these offer the finale listed as IIIa, while the remaining copy, from Genoa, ends with the minuet movement listed as IIIb. The opening Presto centres first on the tonic triad, with a due modulation to the dominant and a development, before the return of the principal theme in recapitulation. The A minor second movement, marked Andante e pianissimo, is chromatic in character, introducing original harmonies. The first finale follows a similar pattern to that of the first movement, while the alternative final Allegro, scored for horns instead of trumpets, as in some copies is the rest of the symphony, offers a movement in the form of a minuet.

Sammartini’s Symphony in C minor, J-C 9, scored, as are the other early symphonies, for strings with continuo, is one of seven in minor keys. This minor key adds an air of dramatic tension to the first movement, with its dotted rhythms, written for three parts, unison violins, violas and bass instruments. This mood of urgency is dispelled in the E flat major second movement, where the melodic burden is carried principally by the first violin, accompanied by second violin, viola and continuo. The final Allegro reverts to three parts, with unison violins, in 3/8, again propelled forward by its accompanying rhythm that continues in accompaniment of the violins, which have the melody throughout.

The Symphony in D major, J-C 16, scored in three parts for violin, viola and bass, opens with a forthright Alla breve movement, bringing characteristic dotted rhythms. The B minor second movement, marked Andante sempre piano, again allows the first violin the melody and its embellishment. There is a lively 3/8 final movement.

The energetic activity of the violins in the Symphony in F major, J-C 36, with its unified opening and in four instrumental parts, recalls the comment of Burney, who was less pleased with this busy feature of Sammartini’s writing, at least when he heard the performance of a Mass in Milan during his visit to the city. The D minor second movement provides the expected contrast, starting with the violins in unison, from which they briefly diverge, before returning to three-part texture for the bulk of the movement. The symphony ends with a vigorous 3/8 Allegro assai, much of it in three parts.

Dotted rhythms mark the opening Allegro of the Symphony in D minor, J-C 23, varied with triplet figuration. The movement is scored for first and second violins with continuo. The pastoral F major slow movement is again in the aria form used by Vivaldi in many of his concertos and in a lilting 12/8. The strongly dotted rhythms and triplets of the first movement return in the final 3/4 Presto.

The Symphony in C major, J-C 4, from about 1750, is scored for two horns and strings. The opening Allegrissimo is in sonata form, with both sections repeated. The short G major slow movment, marked Andante e affettuoso and scored for strings alone, is followed by a final Allegrissimo minuet-type movement with considerable rhythmic variety.

![Nana Vasconcelos - Saudades (1980/2025) [Hi-Res] Nana Vasconcelos - Saudades (1980/2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1766056483_cover.jpg)

![Yasuhiro Usui, Ryoko Ono and Taro Tatsumaki - The House Concert Live Collection, Vol. 55: Yasuhiro Usui (Live at 3rd Floor, Artist House, Daehak-ro, Seoul, 7/12/2015) (2025) [Hi-Res] Yasuhiro Usui, Ryoko Ono and Taro Tatsumaki - The House Concert Live Collection, Vol. 55: Yasuhiro Usui (Live at 3rd Floor, Artist House, Daehak-ro, Seoul, 7/12/2015) (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765791289_rchn1y2nh7yfb_600.jpg)