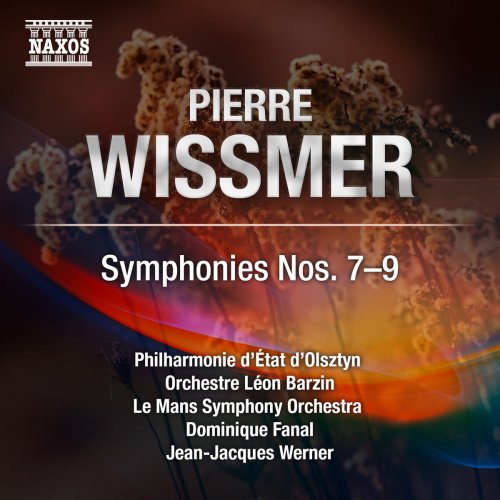

Philharmonie d'Etat d'Olsztyn - Wissmer: Symphonies Nos. 7-9 (2014)

Artist: Philharmonie d'Etat d'Olsztyn

Title: Wissmer: Symphonies Nos. 7-9

Year Of Release: 2014

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 68:51

Total Size: 308 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: Wissmer: Symphonies Nos. 7-9

Year Of Release: 2014

Label: Naxos

Genre: Classical

Quality: FLAC (tracks)

Total Time: 68:51

Total Size: 308 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Symphony No. 7

Conductor: Dominique Fanal - Artists: Philharmonie d'Etat d'Olsztyn & Dominique Fanal

01. I. Lamento (5:44)

02. II. Il cavaliere (7:06)

03. III. Notturno (6:38)

04. IV. Scherzo (5:17)

Symphony No. 8

Conductor: Jean-Jacques Werner - Artists: Leon Barzin Orchestra & Jean-Jacques Werner

05. I. Prologo (1:40)

06. II. Allegro deciso (6:33)

07. III. Notturno (5:13)

08. IV. Tempo giusto (5:25)

Symphony No. 9

Conductor: Dominique Fanal - Artists: Orchestre Symphonique du Mans & Dominique Fanal

09. I. Preludio e allegro (10:21)

10. II. Affettuoso con anima (3:08)

11. III. Finale - Allegro (11:46)

Symphony No 7 (1983–84)

Finished in Valcros on 23 May 1984 and dedicated to the memory of Arthur Honegger, the Seventh Symphony—of Italian inspiration if one is to believe the movement titles—again takes up a lay-out in four very distinct movements yet in the classic succession that Wissmer used in the Third, Fourth and Fifth Symphonies. In fact, the work’s unity is due to its mysterious atmosphere and airy orchestration, towards which each of the parts tends, despite quite characterised accroches. Here, Wissmer strives for an almost Mendelssohnian effect, treating the orchestra in pictorial strokes favouring soli and subtle combinations of timbres, disdaining the power of the tutti.

Perhaps in homage to his teacher and friend Daniel-Lesur, who was particularly fond of this form, the opening Lamento, Largo at the minim, establishes a time stretched to the extreme and in which, after a few gripping dynamic contrasts, the strings sing long, ecstatic laments whilst the harp and chimes scan the sound space with timbre-less chords.

Il Cavaliere, Allegro marziale (4/4), is based on a decaphonic chromatic theme presented in the violins then varied. A timpani solo introduces a central episode characterised by the use of the brass, piccolo and side drum in fanfares like splashes of colour before the return of the strings and a perdendosi ending dying out in silence.

The strangeness that ran through the first two movements is prolonged in the Notturno, Moderato (4/4), which affirms, after two opening chords, a twelve-note row played by the cellos then developed in lyrical melismas by the strings and woodwinds. A quivering of the tutti announces a brief piano solo like the song of a night bird before lugubrious clusters of Bartókian inspiration lead to a return of the strings.

The last movement, entitled Scherzo, Tempo giusto (4/4), presents, on a framework that is still pointillist, sketches of dancing themes: here, a languid waltz in the strings à la Ravel or Strauss, there, a folk-dance played by the English horn, and further on, a graceful recitative in the violins or a facetious counterpoint of the flute and clarinet. The discourse crumbles and dissolves like light waning on a landscape at dusk.

Symphony No 8 (1985–86)

Laid out in three movements, the Eighth Symphony comes back to forces with woodwinds by pairs, revealing the importance of the brass in dialogue with the strings and percussion. Here, after having previously only suggested it, Wissmer comes out and straightforwardly asks the question of whether chromatic or serial dodecaphonic inspiration has run out of steam: can it contribute anything beyond a simple stimulus to the imagination?

Then a few snatches of series, beginnings or fulfilments of themes, dense altered chords or sober common chords announcing the return to a method of composition already rid of its complexes vis-à-vis the avant-garde and opening up to post-modernity, in particular by the gentleness of the final harmonies.

The first movement opens with a brief Prologo, Adagio mesto (4/4), constructed in arch form: the flute articulates the B, then a disjointed theme is exposed by the strings in a C minor colour treated chromatically. It is followed by its dramatic commentary tutti before the return of the strings’ theme and the B, this time played by the oboe. The Prologo runs directly into the Allegro deciso (4/4), which returns to the vein of the last movement of the Seventh Symphony, weaving melodic sketches, sometimes dynamic, sometimes expressive, bringing out the strings, brass and percussion and, after a timpani solo, leading to a brief parody of a Baroque fanfare preceding a return to the lyricism of the strings before the conclusion in D flat.

The Notturno, Moderato assai (3/4), establishes, primarily by interlacings of strings and woodwinds, a vibrant melancholy atmosphere illuminated as a final touch by a C major chord.

In the last movement, Tempo giusto (4/4), Wissmer first goes back to the joy of using the orchestra in large tutti, initially in the chromatic spirit that prevailed in his symphonic output up until then, but the sudden explosion of the lyrical theme in D major played by the strings establishes a feeling of rest. This tonal calm is prolonged in a long variation; chromaticism attempts unsuccessfully to creep in with the flutes: the fullness of the theme engenders other melodies that gently lead the discourse towards the final effacement in the colour of D.

Symphony No 9 (1988–89)

Pierre Wissmer’s last symphony calls for the same forces as the Eighth and is also cast in three movements. It comes back to a chromatic inspiration and is characterised by the fragmentation of the orchestra, handled in strokes, and above all, by the obsessive, haunting presence of silence. This provides a setting for the resonances of timbres and gives the musical framework a character simultaneously meditative, anguished and suspenseful: the penetration of the feeling of finiteness in the imaginative universe and the being in the composer’s world?

The first movement, Preludio e allegro (4/4), announced in a bright colour of D, deploys the orchestra in its entirety round a recurrent rhythmic figure, harp glissandi and rests hatching the musical time, emphasising resonances and giving the whole a very vertical, even martial, character. Brief, witty melodic cells answer each other in imitation, the composer playing on the combinations and oppositions of timbres round chromatic melodic fragments, reserving an important place for the percussion. The final A major chord illuminates the whole and resonates in a fermata before flowing into the second movement, Affettuoso con anima, which begins in 9/8, quickly absorbed by a return to the binary times of 3/4 and 4/4. The timbres are still treated in sections and alliances, pointillist juxtapositions or lilting counterpoints, leaving no room for the tutti and dissolved in a final appoggiatura chord.

The contrast is gripping with the D articulated by the fanfare of trumpets introducing the return of the third movement 4/4 without tempo marking, usually taken Allegro. A dodecaphonic melody is stated by the violins then freely varied before a second trumpet fanfare intones a folk theme, more or less inspired by the bawdy song Trois orfèvres à la Saint Eloi, also varied, in exactly the same spirit as that of the first movement: sarcasms bursting forth from one section to another, streaked with silence, suave harp glissandi and fall on a C sharp major triad murmured by the strings alone.

Finished in Valcros on 23 May 1984 and dedicated to the memory of Arthur Honegger, the Seventh Symphony—of Italian inspiration if one is to believe the movement titles—again takes up a lay-out in four very distinct movements yet in the classic succession that Wissmer used in the Third, Fourth and Fifth Symphonies. In fact, the work’s unity is due to its mysterious atmosphere and airy orchestration, towards which each of the parts tends, despite quite characterised accroches. Here, Wissmer strives for an almost Mendelssohnian effect, treating the orchestra in pictorial strokes favouring soli and subtle combinations of timbres, disdaining the power of the tutti.

Perhaps in homage to his teacher and friend Daniel-Lesur, who was particularly fond of this form, the opening Lamento, Largo at the minim, establishes a time stretched to the extreme and in which, after a few gripping dynamic contrasts, the strings sing long, ecstatic laments whilst the harp and chimes scan the sound space with timbre-less chords.

Il Cavaliere, Allegro marziale (4/4), is based on a decaphonic chromatic theme presented in the violins then varied. A timpani solo introduces a central episode characterised by the use of the brass, piccolo and side drum in fanfares like splashes of colour before the return of the strings and a perdendosi ending dying out in silence.

The strangeness that ran through the first two movements is prolonged in the Notturno, Moderato (4/4), which affirms, after two opening chords, a twelve-note row played by the cellos then developed in lyrical melismas by the strings and woodwinds. A quivering of the tutti announces a brief piano solo like the song of a night bird before lugubrious clusters of Bartókian inspiration lead to a return of the strings.

The last movement, entitled Scherzo, Tempo giusto (4/4), presents, on a framework that is still pointillist, sketches of dancing themes: here, a languid waltz in the strings à la Ravel or Strauss, there, a folk-dance played by the English horn, and further on, a graceful recitative in the violins or a facetious counterpoint of the flute and clarinet. The discourse crumbles and dissolves like light waning on a landscape at dusk.

Symphony No 8 (1985–86)

Laid out in three movements, the Eighth Symphony comes back to forces with woodwinds by pairs, revealing the importance of the brass in dialogue with the strings and percussion. Here, after having previously only suggested it, Wissmer comes out and straightforwardly asks the question of whether chromatic or serial dodecaphonic inspiration has run out of steam: can it contribute anything beyond a simple stimulus to the imagination?

Then a few snatches of series, beginnings or fulfilments of themes, dense altered chords or sober common chords announcing the return to a method of composition already rid of its complexes vis-à-vis the avant-garde and opening up to post-modernity, in particular by the gentleness of the final harmonies.

The first movement opens with a brief Prologo, Adagio mesto (4/4), constructed in arch form: the flute articulates the B, then a disjointed theme is exposed by the strings in a C minor colour treated chromatically. It is followed by its dramatic commentary tutti before the return of the strings’ theme and the B, this time played by the oboe. The Prologo runs directly into the Allegro deciso (4/4), which returns to the vein of the last movement of the Seventh Symphony, weaving melodic sketches, sometimes dynamic, sometimes expressive, bringing out the strings, brass and percussion and, after a timpani solo, leading to a brief parody of a Baroque fanfare preceding a return to the lyricism of the strings before the conclusion in D flat.

The Notturno, Moderato assai (3/4), establishes, primarily by interlacings of strings and woodwinds, a vibrant melancholy atmosphere illuminated as a final touch by a C major chord.

In the last movement, Tempo giusto (4/4), Wissmer first goes back to the joy of using the orchestra in large tutti, initially in the chromatic spirit that prevailed in his symphonic output up until then, but the sudden explosion of the lyrical theme in D major played by the strings establishes a feeling of rest. This tonal calm is prolonged in a long variation; chromaticism attempts unsuccessfully to creep in with the flutes: the fullness of the theme engenders other melodies that gently lead the discourse towards the final effacement in the colour of D.

Symphony No 9 (1988–89)

Pierre Wissmer’s last symphony calls for the same forces as the Eighth and is also cast in three movements. It comes back to a chromatic inspiration and is characterised by the fragmentation of the orchestra, handled in strokes, and above all, by the obsessive, haunting presence of silence. This provides a setting for the resonances of timbres and gives the musical framework a character simultaneously meditative, anguished and suspenseful: the penetration of the feeling of finiteness in the imaginative universe and the being in the composer’s world?

The first movement, Preludio e allegro (4/4), announced in a bright colour of D, deploys the orchestra in its entirety round a recurrent rhythmic figure, harp glissandi and rests hatching the musical time, emphasising resonances and giving the whole a very vertical, even martial, character. Brief, witty melodic cells answer each other in imitation, the composer playing on the combinations and oppositions of timbres round chromatic melodic fragments, reserving an important place for the percussion. The final A major chord illuminates the whole and resonates in a fermata before flowing into the second movement, Affettuoso con anima, which begins in 9/8, quickly absorbed by a return to the binary times of 3/4 and 4/4. The timbres are still treated in sections and alliances, pointillist juxtapositions or lilting counterpoints, leaving no room for the tutti and dissolved in a final appoggiatura chord.

The contrast is gripping with the D articulated by the fanfare of trumpets introducing the return of the third movement 4/4 without tempo marking, usually taken Allegro. A dodecaphonic melody is stated by the violins then freely varied before a second trumpet fanfare intones a folk theme, more or less inspired by the bawdy song Trois orfèvres à la Saint Eloi, also varied, in exactly the same spirit as that of the first movement: sarcasms bursting forth from one section to another, streaked with silence, suave harp glissandi and fall on a C sharp major triad murmured by the strings alone.

Download Link Isra.Cloud

Olsztyn State Philharmonic Orchestra - Wissmer_ Symphonies Nos. 7-9 FLAC.rar - 308.4 MB

Olsztyn State Philharmonic Orchestra - Wissmer_ Symphonies Nos. 7-9 FLAC.rar - 308.4 MB

![Etta Jones - If You Could See Me Now (1979) [Vinyl] Etta Jones - If You Could See Me Now (1979) [Vinyl]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1767962064_5.jpg)

![Robert Stillman - 10,000 Rivers (2026) [Hi-Res] Robert Stillman - 10,000 Rivers (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/10/8jwz0bin2i14qjmws9vecjwx5.jpg)

![Kate Kortum - Wild Woman Tells All (2026) [Hi-Res] Kate Kortum - Wild Woman Tells All (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-01/1767862862_ajiixgeb8lsxc_600.jpg)