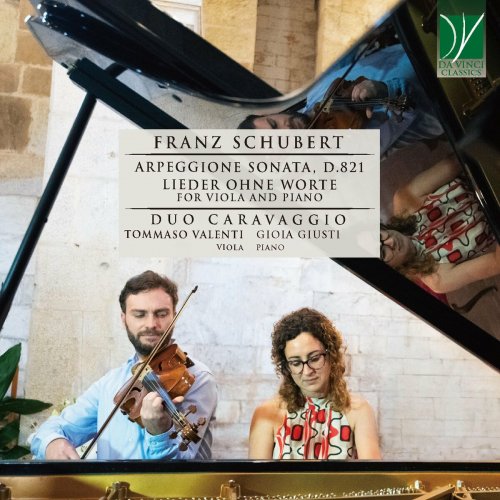

Artist :

Tommaso Valenti, Gioia Giusti, Duo Caravaggio

Title :

Franz schubert: Arpeggione sonata, D.821 & lieder ohne worte for Viola and Piano

Year Of Release :

2022

Label :

Da Vinci Classics

Genre :

Classical

Quality :

FLAC (tracks)

Total Time : 1:11:10

Total Size : 298 MB

WebSite :

Album Preview

Tracklist: 1. Duo Caravaggio – Frühlingsglaube in B-Flat Major, D.686 (03:59)

2. Duo Caravaggio – Lachen und weinen in A-Flat Major, Op. 59, D.777 (02:59)

3. Duo Caravaggio – Die Forelle in D-Flat Major, D.550 (02:52)

4. Duo Caravaggio – Der Tod und das Mädchen in D Minor, Op. 7 No.3, D.531 (03:03)

5. Duo Caravaggio – Gretchen am Spinnrade in D Minor, Op. 2, D.118 (04:09)

6. Duo Caravaggio – Lob der Tränen in D Major, D.711 (04:59)

7. Duo Caravaggio – Auf dem wasser zu singen in A-Flat Major, Op. 72, D.774 (04:18)

8. Duo Caravaggio – Winterreise in D Minor, Op. 89, D.911: I. Gute Nacht (05:13)

9. Duo Caravaggio – Winterreise in A Minor, Op. 89, D.911: II. Die Wetterfahne (02:17)

10. Duo Caravaggio – Ständchen in D Minor, D.957 (05:11)

11. Duo Caravaggio – 4 Gesänge aus Wilhelm Meister in A Minor, D.877: I. Lied Der Mignon. Langsam (03:42)

12. Duo Caravaggio – Litaney auf das Fest Aller Seelen in E-Flat Major, D.343 (03:39)

13. Duo Caravaggio – Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano in A Minor, D.821: I. Allegro moderato (09:39)

14. Duo Caravaggio – Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano in E Major, D.821: II. Adagio (04:44)

15. Duo Caravaggio – Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano in A Major, D.821: III. Allegretto (10:20)

VIDEO

Franz Schubert’s melodies are capable of concentrating many nuanced and very deep feelings within a single design. The phrasing’s regularity, the tendency to move by tones and semitones, the tune’s bending within a well-defined texture seem to indicate a vocal imprint. This is found also in many themes of Sonatas and Quartets, of Trios and Symphonies. This applies not only to the use of specific references, as in the Forellenquintett D 667, in the Wandererfantasie D 760, in the Variations D 802 on Trockne Blumen or in the Quartet D 810, Der Tod und das Mädchen. Beyond the undebatable centrality of vocal music in Schubert’s oeuvre (more than 600 Lieder written between 1811 and 1828), instrumental music in turn absorbs inspiration from the vocal, establishing an osmosis between these two genres which will be adopted by Mahler. Beyond all precise programmatic intentions, it is possible to find, also in the instrumental works, some figurations which Schubert associates, in his Lieder, to the recurring symbols of his poetic world. These include, for instance, water as life’s generating power, but also as mutability and destruction; spring as a comforting mirage within life’s winter; march, associated to the meaningless itinerary of existence; dance as an image of seduction and ebriety. It is interesting to observe their persistence also in the performances presented here, of twelve songs played as Lieder ohne Worte, with the melodies transferred from the voice to the viola.

![Betty Carter - The Music Never Stops (2019) [Hi-Res] Betty Carter - The Music Never Stops (2019) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765896843_bcmn500.jpg)

![Sibel Köse Septet - In Good Company (2025) [Hi-Res] Sibel Köse Septet - In Good Company (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2025-12/1765846644_uizwujac4ht2d_600.jpg)

![Tom Cohen - Embraceable Brazil (2025) [Hi-Res] Tom Cohen - Embraceable Brazil (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2025-12/18/vgt0kbsml69jbixcu67jkruae.jpg)