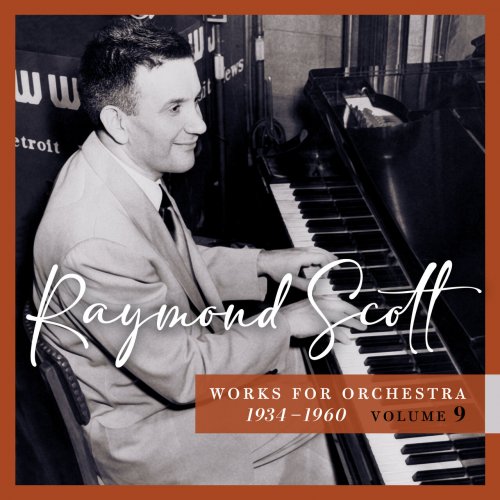

Piero Barbareschi, David Scaroni, Davide Bravo, Andrea Marcolini - Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Quartets (In G Minor KV 478, in E-Flat Major KV 493) (2022)

Artist: Piero Barbareschi, David Scaroni, Davide Bravo, Andrea Marcolini

Title: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Quartets (In G Minor KV 478, in E-Flat Major KV 493)

Year Of Release: 2022

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:03:41

Total Size: 248 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

TracklistTitle: Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Piano Quartets (In G Minor KV 478, in E-Flat Major KV 493)

Year Of Release: 2022

Label: Da Vinci Classics

Genre: Classical

Quality: flac lossless (tracks)

Total Time: 01:03:41

Total Size: 248 mb

WebSite: Album Preview

01. Piano Quartet in G Minor, KV 478: I. Allegro

02. Piano Quartet in G Minor, KV 478: II. Andante

03. Piano Quartet in G Minor, KV 478: III. Rondo

04. Piano Quartet in E-Flat Major, KV 493: I. Allegro

05. Piano Quartet in E-Flat Major, KV 493: II. Larghetto

06. Piano Quartet in E-Flat Major, KV 493: III. Allegretto

Romanticism has sold us the idea of the misunderstood genius. Of course, it is true that some great composers (and some other great figures of human history) were “in advance of their times”, and that their full appreciation came only after their deaths – at times, many decades after that. The typical example, in the musical field, is obviously Bach. Here, too, however, it is true that the “Bach-Renaissance” began only in the nineteenth century, and that his works became widely known only approximately a century after the end of his life. Still, connoisseurs and music specialists had never forgotten Bach, and were passing on knowledge about his works and compositional techniques to their younger colleagues. Among these was also Mozart, who came to know Bach’s works through Gottfried von Swieten, the music lover who disseminated Baroque music in the Vienna of late Classicism.

From his study of Bach, as well as from other great models (and from the teachings of Padre Martini), Mozart had learnt the intricacies of polyphony, and he loved to employ these techniques in virtually all of his best works. And if Bach had been nearly forgotten by many of his contemporaries due to the complexity of his writing, this reproach was frequently expressed against Mozart who, moreover, lived more than a generation after the great German musician. The era of the galanteries was certainly in no mood for severe counterpoint. And whilst Mozart was by no means a “severe” composer (but neither was Bach, in the end!), he knew that a pinch of polyphony could highly enhance the beauty of even his most enchanted melodies.

The problem is that polyphony is difficult to write, but also difficult to play. After the affirmation of tonality, the listeners’ and the performers’ ears are more easily suited to the “harmonic” writing (i.e., melody and accompaniment, preferably in chords or quasi-chords, as in the Alberti bass) than to polyphony. Polyphony requires listeners to divide their attention into various layers, simultaneously happening within the same “aural space”. At times, it is similar to the attempt to listen to two discourses at once. By way of contrast, a harmonically conceived piece is much easier to follow, and, consequently, to play. Especially when playing with others, a polyphonically structured work requires careful listening of all concomitant parts, while also concentrating on what one has to play at the same time.

Now, to ask a question requiring an honest answer. If we imagine ourselves as wealthy members of the Viennese bourgeoisie or as careless aristocrats of Mozart’s time, what kind of music would we like (and would be able) to play for our enjoyment? Surely, a kind of music which requires virtually no practice, no rehearsals, little effort, and affords immediate pleasure and refined distraction. Mozart, of course, was perfectly aware of the tastes of his audience, and of the diktats of his wealthy patrons. Actually, he spent much of his time teaching wealthy damsels, and was perfectly capable of writing “easy” pieces for the amusement of the rich. But, at times, his aspiration to beauty would not let him confine himself to what was required of him.

Thus, when in 1785 the publisher Franz Anton Hoffmeister commissioned him a set of three Piano Quartets, Mozart was quick to agree. The genre, in itself, was a novelty, as was the ensemble performing it. It could be seen as a piano trio with added viola, or as the descendant (far removed) of the Trio Sonata. Mozart himself had transcribed, in his childhood and adolescence, some keyboard Concertos by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach for a similar ensemble. (And, curiously, in those same years the adolescent Beethoven was composing his own Piano Quartets, of course unbeknownst to Mozart).

Mozart had also written three of his Piano Concertos (i.e. KV 413, 414 and 415) for a similar readership, providing them with an alternative scoring for piano and strings which is only slightly different from that of the Piano Quartets. However, as had happened with the three Concertos, here too the task he had set for himself was not entirely fulfilled. Or, to be more precise, was abundantly exceeded. The result of his compositional activity was the magnificent Piano Quartet in G minor, recorded here with its brother, the E-flat major Quartet.

In October 1785, Mozart had completed his first Piano Quartet, and sent it to the publisher, as agreed. Upon receiving it, however, Hoffmeister was clearly disappointed. Being a composer himself, he was probably delighted by the exquisite beauty of the work. But being and entrepreneur, he clearly perceived that this was more than he bargained for. The wealthy, lazy aristocrats who would purchase it, or leaf through it, would quickly realise that a) it was far too difficult for them to play; b) it was far too difficult to be performed by an ensemble of amateurs; c) it was far too serious for an evening of Hausmusik. It was as if one was set on reading an Agatha Christie novel and found Tolstoy’s War and Peace instead.

Was therefore Mozart a misunderstood genius in turn? Partially, yes, of course; but partially, market had its own rules, and, on this occasion, Mozart had failed to play by them. The work sold very little. Hoffmeister allowed Mozart to keep the advance payment he had received for the set of three quartets, but, please, not to write the other two. Hoffmeister was actually, if sadly, right. This was proved by a review appearing in 1788, which describes the catastrophes happening when such a difficult work is attempted by unsupervised amateurs. “Any work speaks for itself when you hear it performed directly before you; this piece by Mozart, if in the hands of a dilettante and performed without due care, could truly not be listened to. That happened last winter on countless occasions… Some young lady, or a confident bourgeois girl, or a dilettante upstart zealously attacked the Quadro at a noisy gathering, claiming that she liked it”. Of course, and quite predictably, the result “could not please: everybody yawned with boredom over the incomprehensible tintamarre of 4 instruments which did not keep together for four bars on end, and whose senseless concentus never allowed any unity of feeling; but it had to please, it had to be praised! … what a difference when this much-advertised work of art is performed with the highest degree of accuracy by four skilled musicians who have studied it carefully”. The anonymous reviewer is not entirely wrong: this is music for professional, and for professionals who have studied and rehearsed it.

In the end, Mozart did write another Piano Quartet (though he did not try and sell it to Hoffmeister); evidently, the challenge had been particularly pleasing for him. In this new genre, he had been able to combine the ability he had conquered in one of his favourite forms, that of the Piano Concerto, with a more intimate setting and lighter scoring, where, moreover, the instruments interact in a closer and more direct fashion.

The first Piano Quartet is in the sombre key of G minor, frequently bound, in Mozart, to dark atmospheres, and to obscure feelings. Operatic gestures are found everywhere in both Quartets; and these may take the shape of both tragic heroes and of coquettish comical characters. In a manner of speaking, in this first Piano Quartet we find both the Queen of the Night (in the first movement) and Papageno (in the humorous and chattering Finale). In the second Quartet, there is the Magic Flute’s solemnity (in the radiant opening, in the Masonic key of E-flat major) and the poetry of the Countess or of Pamina or Donna Elvira. The piano is at times the unrivalled soloist, in the fashion of a virtuoso Piano Concerto, and at times the mere continuo supporting the strings’ evolutions. Theatrical gestures, full of tragic pathos or of awe-inspiring magnificence make us forget that just four performers are playing together; at the same time, in the most intimate moments, we are drawn into a dialogue so secretive and personal that we dare not breathe. The slow movements of both Quartets are among Mozart’s finest chamber music realisations; his ability to create enchanted atmospheres, as in the garden scenes of his operas, is fully employed in these movements full of lyricism, poetry, and tenderness.

The Finales, as would be expected, are more brilliant and virtuosic, humorous and chatty; however, it is a very refined kind of amusement, where even the comical element is, in a manner of speaking, suited to the general level of the composition and to the composer’s evident ambition to create masterpieces out of this new genre.

And masterpieces he did create. These Quartets are two examples (not the only ones) of Mozart’s capability to virtually create a new genre and to bring it to perfection at the same time. Later composers could only admire and refer to these splendid achievements; they would also draw inspiration from many of Mozart’s ideas, and transfer them to other domains. Interestingly, Franz Joseph Haydn was going to pay an implicit, but clear, homage to Mozart’s E-flat Quartet in the very last keyboard Sonata he would write. Thus, if Mozart had perhaps failed to please the amateurs, he had certainly not disappointed the connoisseurs.

![Toc - Quelques idées d’un vert incolore dorment furieusement (2025) [Hi-Res] Toc - Quelques idées d’un vert incolore dorment furieusement (2025) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/03/2p7a6y1mdz29most6p7irqo6y.jpg)

![Oiro Pena - Oiro Pena (2020) [Hi-Res] Oiro Pena - Oiro Pena (2020) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-01/04/r18zex2qlhbhk9ouirvlgxcm2.jpg)

![Oleksandr Kolosii - Paws Up (2023) [Hi-Res] Oleksandr Kolosii - Paws Up (2023) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2023-04/1681924828_folder.jpg)