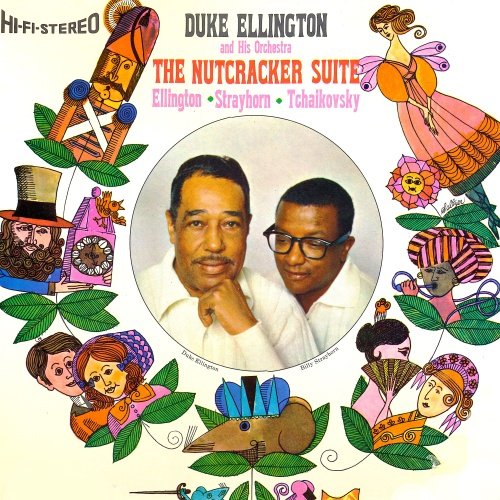

Duke Ellington - The Nutcracker Suite (1960/2011) [Hi-Res]

Artist: Duke Ellington

Title: The Nutcracker Suite

Year Of Release: 1960/2011

Label: RevOla

Genre: Jazz

Quality: FLAC (tracks) 24/44,1, 320 kbps

Total Time: 00:30:50

Total Size: 388 / 122 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

Tracklist:Title: The Nutcracker Suite

Year Of Release: 1960/2011

Label: RevOla

Genre: Jazz

Quality: FLAC (tracks) 24/44,1, 320 kbps

Total Time: 00:30:50

Total Size: 388 / 122 MB

WebSite: Album Preview

01 - Overture 03:20

02 - Toot Toot Tootie Toot (Dance of the Reed-Pipes) 02:29

03 - Peanut Brittle Brigade (March) 04:37

04 - Sugar Rum Cherry (Dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy) 03:03

05 - Entr'acte 01:52

06 - The Volga Vouty (Russian Dance) 02:52

07 - Chinoiserie (Chinese Dance) 02:51

08 - Danse of the Floreadores (Waltz of the Flowers) 04:03

09 - Arabesque Cookie (Arabian Dance) 05:43

The Christmas Eve setting of Tchaikovsky’s ballet, The Nutcracker, has helped it to become one of America’s most beloved Christmas traditions, even though the composer had nothing of the sort in mind. (You can thank the San Francisco Ballet of the 1940s.) By 1960, the potential appeal of updating Tchaikovsky’s score was obvious enough to a savvy musician like Duke Ellington. Moreover, Ellington had always been interested in long-form composition, exploring the fusion of classical techniques with jazz style in works like his Creole Rhapsody (1931) and his concerto for trumpeter Cootie Williams, Concerto for Cootie (1940). After offering his take on the Nutcracker Suite, with Billy Strayhorn as arranger, he would go on to write the Far East Suite (1966, also with Strayhorn), the New Orleans Suite (1970), and a jazz version of the Christian liturgy in his Sacred Concerts of the 1960s.

Although separated by a century, the demands of the Romantic-era Russian ballet and the elaborate stage shows of New York City‘s Cotton Club in the late 1920s presented similar challenges to Tchaikovsky and Ellington. The need for variety was paramount, meaning constant shifts in musical mood and style, but at the same time continuity was necessary. Exoticism was an audience favorite in both settings, and each composer had to take into account the choreography, making sure rhythms and tempos would allow the dancers to show their skills to the best effect.

The overtures to both suites set the tone and show the range of timbre, volume, and articulation possible in each of their respective orchestras. Both are also elegant and balanced, whether in terms of the classicism that Tchaikovsky gleaned from Mozart and Haydn or the carefully calibrated swing of Ellington’s band. What typically follows in any concert performance of Tchaikovsky’s suite is a selection from among the “characteristic dances,” which contrast style, tempo, and orchestration in order to conjure the various members of the court of the Sugar-Plum Fairy. As most conductors do, Ellington selected some, but not all, of these dances in order to show off the members of his band.

Ellington’s “Toot, Toot, Tootie, Toot” is the closest to its source material, although the innovations set the tone for what is to come. Where Tchaikovsky had piping flutes and bassoons over a quiet string ostinato, Ellington has the reed section divided into clarinets and saxes in close alternation, over a relaxed groove in the rhythm section, with more forceful interjections from the brass. The melancholy, resonant English horn solo becomes a series of broad smears with cup mutes in the trombones. Where the middle portion of Tchaikovsky’s dance is an exoticized whirling dervish, with trumpets over an ostinato in the low strings and brass, Ellington instead lets the band break out into an improvisatory section with the clarinet in the lead.

The two marches also make for an interesting comparison—similar in spirit but executed on their own terms. Tchaikovsky’s quick marche militaire is all about precision of articulation and brilliance in figuration and orchestration. Although the brightness of trumpet also figures in Ellington’s “Peanut Brittle Brigade,” the virtuosity shines through most clearly in a series of up-tempo, boppish solo choruses for trumpet, clarinet, tenor sax, and piano.

Tchaikovsky’s indifference to his own score for The Nutcracker is famous, but the “Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy” allowed him to showcase a new instrument that fascinated him—the celesta—making it perhaps the only part of the score he was pleased with. The twinkling, ethereal sound of the instrument, accompanied only by delicate pizzicati, does make for a magical atmosphere—and it is here that Ellington and Strayhorn part ways with Tchaikovsky in all but the melody they borrowed. Over a slow vamp from the drummer, using the evocative toms, the tenor saxophone struts through “Sugar Rum Cherry,” encouraged by occasional smears and growls in the brass.

In the “national dances,” Tchaikovsky and Ellington drift back together, as both were well-versed in the entertainment value of music that could evoke place, race, or ethnicity. The blistering trepak of Tchaikovsky’s Russian Dance becomes the energetic bounce of the “Volga Vouty.” Ellington and Strayhorn seem to acknowledge their artifice in “Chinoiserie,” which meanders, wheezes, and pops, compared to Tchaikovsky’s swift, chattering Chinese Dance, where his unironic Orientalism is on full display. In another reversal, Tchaikovsky’s graceful, but somewhat melancholy and restrained “Waltz of the Flowers” becomes an opportunity for almost every member of the band to have a virtuosic turn in the rousing series of swing choruses that make up “Dance of the Floreadores.”

To finish their suite, Ellington and Strayhorn put a modern spin on the Arabian Dance with the sort of exoticism that would be on full display in their Far East Suite. Tchaikovsky’s low string ostinato becomes a slow groove for bass and drums and they relocate the “snake charmer” oboe melody from the end of the Arab Dance to a flute solo at the beginning of their “Arabesque Cookie.” Clarinet and bass clarinet are featured in both, and although Ellington and Strayhorn leave out some details, like the tambourine, they add their own flourishes, working with mutes and slides and allowing the tune to swing out briefly before fading away.

The process of adaptation that Ellington and Strayhorn began continues today in new productions, like the Oregon Ballet Theater’s revision of George Balanchine’s Nutcracker to exclude problematic elements like the “yellowface” of the Chinese Dance. This Christmas season, the Joffrey Ballet will premiere an entirely new scenario and choreography from Christopher Weeldon, set at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Traditions that are meant to continue bringing people together cannot remain unchanged—adding a verse to the carol only gives us a little more time to sing together.

Although separated by a century, the demands of the Romantic-era Russian ballet and the elaborate stage shows of New York City‘s Cotton Club in the late 1920s presented similar challenges to Tchaikovsky and Ellington. The need for variety was paramount, meaning constant shifts in musical mood and style, but at the same time continuity was necessary. Exoticism was an audience favorite in both settings, and each composer had to take into account the choreography, making sure rhythms and tempos would allow the dancers to show their skills to the best effect.

The overtures to both suites set the tone and show the range of timbre, volume, and articulation possible in each of their respective orchestras. Both are also elegant and balanced, whether in terms of the classicism that Tchaikovsky gleaned from Mozart and Haydn or the carefully calibrated swing of Ellington’s band. What typically follows in any concert performance of Tchaikovsky’s suite is a selection from among the “characteristic dances,” which contrast style, tempo, and orchestration in order to conjure the various members of the court of the Sugar-Plum Fairy. As most conductors do, Ellington selected some, but not all, of these dances in order to show off the members of his band.

Ellington’s “Toot, Toot, Tootie, Toot” is the closest to its source material, although the innovations set the tone for what is to come. Where Tchaikovsky had piping flutes and bassoons over a quiet string ostinato, Ellington has the reed section divided into clarinets and saxes in close alternation, over a relaxed groove in the rhythm section, with more forceful interjections from the brass. The melancholy, resonant English horn solo becomes a series of broad smears with cup mutes in the trombones. Where the middle portion of Tchaikovsky’s dance is an exoticized whirling dervish, with trumpets over an ostinato in the low strings and brass, Ellington instead lets the band break out into an improvisatory section with the clarinet in the lead.

The two marches also make for an interesting comparison—similar in spirit but executed on their own terms. Tchaikovsky’s quick marche militaire is all about precision of articulation and brilliance in figuration and orchestration. Although the brightness of trumpet also figures in Ellington’s “Peanut Brittle Brigade,” the virtuosity shines through most clearly in a series of up-tempo, boppish solo choruses for trumpet, clarinet, tenor sax, and piano.

Tchaikovsky’s indifference to his own score for The Nutcracker is famous, but the “Dance of the Sugar-Plum Fairy” allowed him to showcase a new instrument that fascinated him—the celesta—making it perhaps the only part of the score he was pleased with. The twinkling, ethereal sound of the instrument, accompanied only by delicate pizzicati, does make for a magical atmosphere—and it is here that Ellington and Strayhorn part ways with Tchaikovsky in all but the melody they borrowed. Over a slow vamp from the drummer, using the evocative toms, the tenor saxophone struts through “Sugar Rum Cherry,” encouraged by occasional smears and growls in the brass.

In the “national dances,” Tchaikovsky and Ellington drift back together, as both were well-versed in the entertainment value of music that could evoke place, race, or ethnicity. The blistering trepak of Tchaikovsky’s Russian Dance becomes the energetic bounce of the “Volga Vouty.” Ellington and Strayhorn seem to acknowledge their artifice in “Chinoiserie,” which meanders, wheezes, and pops, compared to Tchaikovsky’s swift, chattering Chinese Dance, where his unironic Orientalism is on full display. In another reversal, Tchaikovsky’s graceful, but somewhat melancholy and restrained “Waltz of the Flowers” becomes an opportunity for almost every member of the band to have a virtuosic turn in the rousing series of swing choruses that make up “Dance of the Floreadores.”

To finish their suite, Ellington and Strayhorn put a modern spin on the Arabian Dance with the sort of exoticism that would be on full display in their Far East Suite. Tchaikovsky’s low string ostinato becomes a slow groove for bass and drums and they relocate the “snake charmer” oboe melody from the end of the Arab Dance to a flute solo at the beginning of their “Arabesque Cookie.” Clarinet and bass clarinet are featured in both, and although Ellington and Strayhorn leave out some details, like the tambourine, they add their own flourishes, working with mutes and slides and allowing the tune to swing out briefly before fading away.

The process of adaptation that Ellington and Strayhorn began continues today in new productions, like the Oregon Ballet Theater’s revision of George Balanchine’s Nutcracker to exclude problematic elements like the “yellowface” of the Chinese Dance. This Christmas season, the Joffrey Ballet will premiere an entirely new scenario and choreography from Christopher Weeldon, set at the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago. Traditions that are meant to continue bringing people together cannot remain unchanged—adding a verse to the carol only gives us a little more time to sing together.

![Manu Delago & Max ZT - Deuce (2026) [Hi-Res] Manu Delago & Max ZT - Deuce (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://img.israbox.com/img/2026-02/19/v5s18xsisjkqnsg5od9qlgck5.jpg)

![Matt Monro - Matt Sings Monro (Live at the BBC, Remastered 2023) [Hi-Res] Matt Monro - Matt Sings Monro (Live at the BBC, Remastered 2023) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771586614_k3yj19donljhc_600.jpg)

![Vivian Rosie - Twilight Voodoo (2026 Remaster) [Hi-Res] Vivian Rosie - Twilight Voodoo (2026 Remaster) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771389602_cover.jpg)

![Matt Monro - The Nearness Of You (2015) [Hi-Res] Matt Monro - The Nearness Of You (2015) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771594612_cover.jpg)

![Kento Tsubosaka - Lines (2026) [Hi-Res] Kento Tsubosaka - Lines (2026) [Hi-Res]](https://www.dibpic.com/uploads/posts/2026-02/1771391986_zw4gprxc9nex6_600.jpg)